Report of the Task Force on the Future of

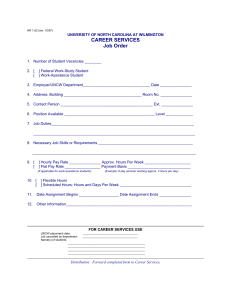

advertisement