Joanne Scott and Jane Holder

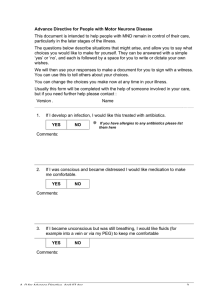

advertisement