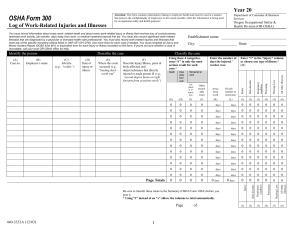

HIDDEN TRAGEDY: Underreporting of Workplace Injuries and Illnesses

advertisement