Document 11987466

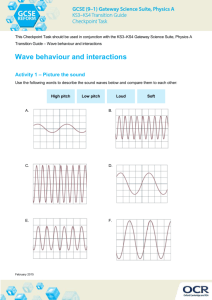

advertisement