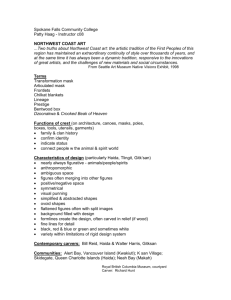

Anthropology, History, Education, Art

advertisement