AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF in Interdisciplinary Studies:

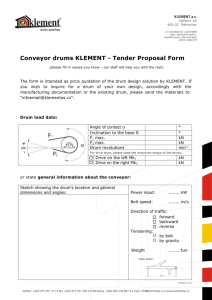

advertisement