AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF MASTER OF ARTS IN INTER-

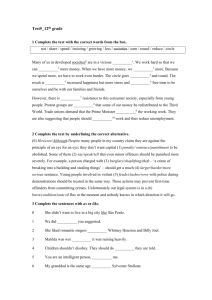

advertisement