Document 11985312

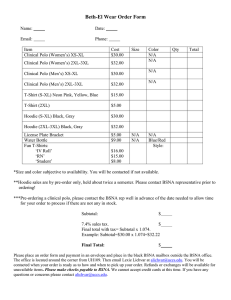

advertisement