: A Zine on Writing at Queens College From the Editors

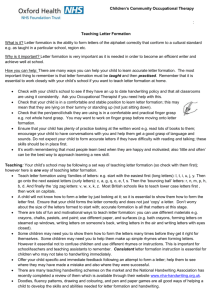

advertisement