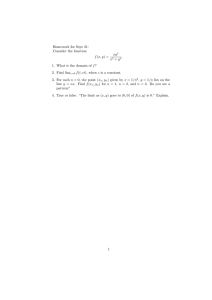

By Hugo L. Jr. Kons University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point

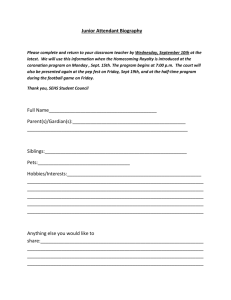

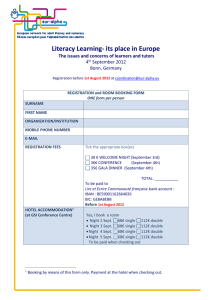

advertisement