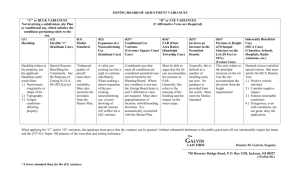

Zoning Nonconformities Application of new rules to existing development Written by Lynn Markham

advertisement