Document 11951169

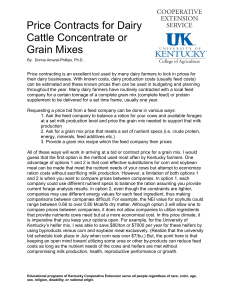

advertisement