Table of Contents What You’ll Find in This Packet

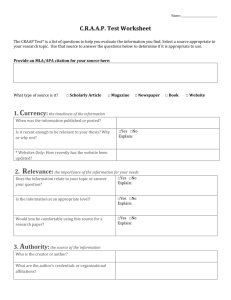

advertisement