A Tool for National Forest

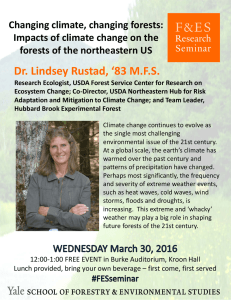

advertisement

Policy Functional Communities ATool forNational Forest Planning (USDA-FS1990a,p. 13). he175unitsoftheNational For- schedules" estSystem arepreparing to revise The conceptof functionalcom- Working withresidents ofnorthern Wisconsin. theauthors found15functional theforestplansthathaveguided munity-geographicareasin which communities inand around theChequamegon of andrelatheirmanagement decisions formore peopleshareperceptions than a decade. The first round of naandNicoletNational Forests. Functional tionshipsto forestsand naturalreprovedusefulin gathercommunities aregeographic areas inwhich tionalforestplanningwascriticized sources--has people share perceptions ofandrelationshipsfor not providingdecisionmakersing and organizingsocialinformawith enough social information tion for forestplanning.Although to forests andnaturalresources. Several (USDA-FS 1990a). the followingexampleis from the issues were raised byresidents inall One teamcharged with critiquing Chequamegon andNicoletNational communities, including concern about thenationalforestplansreported,"We Forests,the conceptis applicable development, high property taxes, day-use apparently provided thedecision mak- across all landmanagement agencies. fees, maintaining access tonatural resources,ers with reams of FORPLAN results andmaintaining thehealth andproductivityandresource databut with verylittle Social Assessment The authors identified functional offorest ecosystems. Forest planners will information onthedemographics, culneedto address theseconcerns. ture, or lifestyleof constituents..." communities aspartof a socialassess(USDA-FS1990b,p. 14). mentfortheChequamegon andNicoAnother team observed that on na- letNationalForests in Wisconsin(Jakes In theUSDAForest Sertional forestswherethe planning etal.in press). By PamelaJakes,Thomas Fish, is a "broad level process wassuccessful, "Theattention vice, a socialassessment topeople's needs (emotional, symbolic, or programmatic datacollectionand and organizational, as well as eco- analysis process usedto generate infor(USDA-FS about 1995, the p. social 2.2). environment" The social asnomic and communityneeds)were mation givenconsideration alongwiththeresourcecapabilitiesand commodity sessment is not a decision document Deborah Carr, and Dale Blahna Residents of northern Wisconsin identified 15 functionalcommunities (red), definedasgeographicareas where residents relate to and Ashland Drummond usethe Chequamegon and Land O'Lakes Nicolet National Forests Glidden (green)in similarways. Florence Park Falls Phillips Gilman Eagle River Lake Laona Medford Lakewood 0 • 25 50 75 100 ! Kilometers Peer-Reviewed Journalof Forestry 33 buta description of past,present, and makesense outof thingstheyseeand but most often we met at the local potentialsocialconditions. Although cannotpredictin advance (Branden- rangerstation. Wemetduringtheday, Chequamegon-Nicolet forest managersburget al. 1995).Althoughwhenwe overlunch, and after businesshours. Our first task was to have residents recognized thatpeople throughout the beganourfieldworkwe assumed that Midwest had concerns about national communities would coalesce around identifygeographic areas thatmightbe forest management, theywanted theso- employment, ourmodels weresubject functionalcommunities. We placeda cialassessment to focusonthepeople to change depending onwhatweheard pieceof Mylarovera mapof Wisconandtheareamostdirectlyaffected by andobserved. Theideaofoccupationalsin and asked them to look at the retheir decisions--year-round residents communityis not new and hasbeen gionwithwhichtheyweremostfamilin northern Wisconsin. found common in the western United iar andcirclethe areaswherepeople Oneofthefirstchallenges wefaced States(Salaman1974; Carrolland Lee use and relate to the forests and natural wasmakingtheinformation usefulto 1990). resources in similarways. Given the time limitations,we conplanners. The assessment needed to orWe thenaskedquestions developed ganizethenearlyhalf-million people centrated on identifying communities to solicitperceptions of howtheyand livingon or neartheChequamegon-in theimmediate proximity of thetwo theirneighbors think aboutanduse Nicoletintomanageable units.It also the Chequamegon and NicoletNaneeded to provide theplanning team tionalForests andothernearbyforestwith as much information as time allands0akeset al. in press). It wasnot lowedaboutconcerns regarding future uncommonfor peopleto fine-tune forestmanagement. Finally,theinfortheirmaps,changing theboundaries to mation neededto be linked to the land- scape, showing theconnection between wherepeople liveandtheirconcerns. Weusedtwoapproaches to organizinginformation on northernWisconsin. First,we lookedat categorical groups--groups that havesimilarsta- exclude some areas and include others IdentiJ)ing functionalcommunities When all the interviews were com- pleted,weoverlaid thesheets ofMylar and,takingintoaccount theinformaLeet al. 1990,p. 9 tion from the interviews, drew boundaries for 15 Chequamegon- tistical or definitional characteristics Nicolet functional communities. The (Flynn 1985). We usedUS Census national forests. We madeno attempt datato describe the groupof people to identifycommunities outsidethis whoareresidents (byageandeduca- areaor incorporate communities of intion),andanother groupconsisting of terestrepresented by visitorsandsea- boundaries arenotsacrosanct butgenerallydelineateareaswherepeople households (by incomeandtypeof sonal residents.We focused on assesshousing). ingthenoneconomic socialaspects of Functional groups, oursecond ap- communities;no economicanalysis proach, gobeyond dataandshowpeo- was done. A full discussion of our ple'sbehaviorand their interactions methodology canbefoundin Jakes et with eachother(Flynn1985).They al. (in press). arecreatednot by theanalystbut by Selecting keyinj•rmants. We asked socialconditions.For the Chequa- the five district rangerson the megon-Nicolet socialassessment, the Chequamegon-Nicolet to identify social conditions of interest were resi- shareforest-relatedinterests,relation- ships,andconcerns. A significant part of the populationendedup outside the functional communities we iden- tified,butjustasfunctional communities are not meant to be all-inclu- sive,so the boundariesdo not indicate wallsbetweengroupsof people.The shapes merelymapthe differences in the waypeopleuseandrelateto the national forests. "keyinformants" whowouldbe able Community profiles.Information dents' economic, political, community, to discuss the relationshipbetween from the interviews helpeduswrite and cultural ties to the areasnatural rethe residents and the national forests. communityprofiles.Profilesinclude sources.To define functional commuFromthe listsprovidedby the dis- descriptions of the communityas a nitiesandseehowpeoplerelateto and trict rangers,we tried to interviewat whole,thecommunity's relationship to useforests,we relied on interviews. leastfour peoplein eachrangerdis- forestresources andpubliclands,and trict--generally two ForestService the community's relationship to the Methods employees and two non-ForestSer- national forests andperceptions of naWe useda process referred to asan- vice employees. Althoughwe were tionalforestpolicies andemployees. A alyticalinductionto developfunc- interested in the diverse views of res- list of issues importantto the infortional communities for the Cheidentsin andaroundeachrangerdis- mantscompleted theprofile. quamegon-NicoletNational Forests trict,wedid nottry to find represen(Brandenburgand Carroll 1995). tatives of all interests. Findings With analytical induction,researchers Interviews. We interviewed 46 yearRatherthan identifyingcommudonotbeginfieldwork withprecisely roundresidents duringSeptember and nitiesbyoccupation, asweexpected, definedhypotheses to be tested,but earlyOctober1996.We met at mills, the residents of northern Wisconsin rather, goto thefieldin anattempt to retailstores, campgrounds, andresorts, identifiedcommunitiesby culture, :34 March 1998 tradition, and leisure activities. Our highpropertytaxesandto a certainex- •nformants believed that both new tent blamed them on the need to make and long-time residentsof our Chequamegon-Nicolet communities hvedwherethey did because of the highqualityof life. This qualityof hfe depends on access to the North Woods, including its lakes and streams:being able to spend an eveningdrivingall-terrainvehicles (ATV)orcross-country skiing,being able to hunt or fish just minutes fromhome,andhavingaccess to the experiencesand resourcesof the Chequamegon andNicoletNational Forests. Peoplein northernWisconsin were definingthemselves and theirneighbors basedon howthey hvedtheir lives,not by how they earneda living. Theprocess usedto identifyfunc- upfor incomenotbeinggenerated by publicland. However,residents also accepted high taxesas the priceof maintaining the highqualityof life theyvalued-•aqualityof lifedirectly estplansaspromises--promises that were brokenwhen output targets weren't met. Some residents didn't un- derstand that outputshad changed withchanging conditions andassumptions. In some cases,when residents didunderstand theplanning process, forestmanagers neglected to inform The issueof day-use feescameup them of changingconditions,so oftenduringdiscussions of taxes.Al- changes in outputs appeared arbitrary. thoughfeesarebeingcharged ononly Anotherissuewaspublicinvolveone districtof the Chequamegon- mentin forestplanning.Many resiNicolet,residents objectbecause they dentsexpressed interest in participatbelieve theyhavepaidforthemanage- ingmorefully,andoneobserved that ment and use of national forests "thekeyto successful management is throughtheir incomeand property goingto beincluding community resitaxes. Theyviewday-use feesasanat- dentsin theplanning process." temptto charge thema thirdtimefor Finally, key informantsrecogaccess or services they'vealready paid nizedtheimportance of maintaining for twice. thehealthandproductivity of forest Despitecomplaints abouttheper- ecosystems but did not seeecosystem uonal communities revealed the issonalcostofhavinga national forestas health as an end in itself. The health suesthat wereimportantin different a neighbor, therewasno support for and vitality of their northernWisareas.For example,one residentof changing theownership ofthese lands. consin communities depend on the ParkFallscommunitycharacter- Residents toldustheywantedto keep maintainingand improvingecosys•zedhishomeasthe"fumecapitalof publiclandsin publichandsbecause temhealth.Theywantto seethesonorthernWisconsin." Peoplein this thenational forests provided access to cial impactsof forestmanagement area love their snowmobiles and resources thatwerequicklydisappear- decisionsanalyzedand discussed, ATVs, and any forestmanagement ing. They seelandsthat wereonce but they are concernedabout the decisionaffectingmotorizedrecre- open to the public being locked balance between local and national ationusewouldbeof paramount in- away--fordevelopment thatresidents priorities.We wereasked,"Why do terest.On theeastern edgeof there- areunableto participate in because of nationalconcernsalwaysoverride gion,in the Florencecommunity,a therisingcosts of forestandlakeshore local issues or concerns?" resident labeled that area the "silent property--and onepersonexpressed sportcapitalof Wisconsin" because angerabout"out-of-state developers I}iscussion manyresidents' livesrevolvedaround wantingto makea fastbuck."Another The qualitativeinformationcolwhite-water recreational opportuni- residentobservedthat "without the na- lectedthrough interviews andusedto ues and activities. The residents of tional forests we would see twice the develop community profiles canbean the Laona communitywere con- development and a hodgepodge of importantcomponentof agencies' cernedaboutpossible miningdevel- land use." public involvement. Information opmentand its potentialimpacton Almosteveryonerecognized that from interviews can add texture and waterquality. therewouldbesome change in theway depthto thediscussion of programs Althougheach communitywas thattheirforests manage ATVs.Cur- andissues during"Friends of theForunique,severalthemesrecurred.All rentlythe Chequamegon's trailsand est"meetings andotheroutreach efthecommunities haveexperienced an roadsareopento ATVs,buttheNico- forts.Informationfrom key inforrefluxofpeople (either seasonal orper- let is closed. Peopleon the Chequa- mantshelpsroundout the list of ismanentresidents) andweregrappling megonrealizethattheywill seesome suesmanagers developaspartof the withtheaccompanying development.restrictions on ATVs,andpeopleon forestplanningprocess and enables Suchgrowthissignificant to national the Nicolet realize that some ATV use them to anticipateresponses to forest managers because it brings into will becomelegal.One Nicoletresi- changesin forestmanagement. Fitheforestmoreandperhaps different denttoldusthatwouldbeall right, nally,interviews aretwo-waystreets, people whowill demand moreanddif- "justsoit isn'twideopenlikeon the withopportunities notonlyfortheinferent benefits. As one resident obterviewer to listen and learn, but also Chequamegon." served, new residents "don't underMany of our key informantsex- for the subjectto askaboutnational standthehistoryandtraditionof the pressed confusion andfrustration over forestmanagement anduse. community andhowwe benefitfrom theforestplanningprocess. TheyinThe importanceof that last goodforest management." terpretedthe harvestquantitiesand point--that interviewsinitiate diaMany peoplecomplainedabout otheroutputs specified in thefirstfor- loguebetweenForestServicemantied to the national forests. Journal of Forestry 35 Kendall/Huntß agersand residents--should not be tional communities are used. CheBtERNACKL P.,andD. WALDORF. 1981.Snowball samoverlooked. No onetechnique canre- quamegon-Nicolet forestmanagers can plingmethod: Problems andtechniques ofchain resolveall the complexity andconflict useourreportto helpidentify prelimferral samplingß Sociological Metboth Research 10(2) 141-63. potential stakeinvolvedin public forestmanage- inaryplanningissues, A.M., and M.S. CARROLL. 1995.Your ment,butapproaches thatbringpeo- holders,communitiesof interest,and BRANDENBURG, place or mine?: The effect of place creation onenvtpletogether to talkwithoneanother socialandpoliticalhotspots. The soronmental values andlandscape meanings. Society alsoprovides valuable andNaturalResources andlearnfromeachotherbeginthe cialassessment 8(5):381-98. dataforenvironmental impact BRANDENBURG, process of buildingtrustingrelation- baseline A.Mß,M.S. CARROLL, andK.A. BLATships--a critical part of successful statements. Improvements in identifyhER. 1995.Towardssuccessful forestplanning through locally based qualitative sociology. !3&stern publicparticipation (Barber1981). ingcommunities anddeveloping comJournal ofApplied Fores•10(3):95-100. Improvingthe process. To better munityprofileswill comewhenwe M.S.,andR.G. LI•E.1990.Occupational identifyfunctionalcommunities, re- havea betterunderstanding of how CARROLL, community andidentity among Pacific Northwest searchers shouldspendtimefinding managers usetheseassessments, and loggers: Implications for adapting to economic people tointerview. A district ranger or whenmanagers havea betterideawhat changes. In Community andJ3rest•: Continuities m thesociology ofnatural resources, eds.R.G.Lee,D R otherlocallandmanager canprovide a mightbe possible in an analysis of Field,andW.R. BurchJr., 141-55.Boulder, CO goodinitiallist,butasweinterviewed functional communities. Westview Press. residents,we realized that there were Furtherapplications. Besides its use FL';S•,J. 1985.A group ecology method forsocial imothers whocouldhavehelped usdraw in preparing notices ofintentandpubpactassessment. Social Impact Assessment 99-100 thecommunity profiles. If wehadhad licinvolvement processes, theconcept 12-24. EJ.,T.E. FISH,D.S. CARR, andD. BLAHNA. In moretime,wewouldhaveexpanded of functional communities is applica- JAKES, press. Practical social assessments fir nationaI Jbrest our list of key informantsusinga bleto otherplanning activities, particplanning. Gen.Tech. Rep. NC-. St.Paul: USDAForsnowballing technique (Biernacki and ularlythedevelopment of ForestSerestService. Waldorf 1981). vice socialimpactanalyses. These LEE,R.G, D.R. FIELD,andW.R.BURCHJR.1990.InIdentification of functional comanalyses aredefinedas"acomponent troduction: Forestry, community, andsociology of resources. In Community andj3restry: Conumunities should precede forest planre- of theenvironmental analysis process natural nuities in thesociology ofnatural resources, eds.R G vision.Informationfromcommunity in which social science information Lee,D.R. Field,andW.R.Burch Jr.,3-13. Boulder, profiles wouldprovide valuable input andmethodology areusedto evaluate CO: Westview Pressß for the notice of intent, which identior projecthowpresentprograms or SALAMAN, G. 1974.Community andoccupation: Anexfiesissues to beaddressed in planrevi- proposed actionsmayaffecthumans" ploration ofwork/leisure relationships. NewYork: Cambridge University Press. sion,andbackground for developing (USDA-FS1995,p. 2.2). (USDA-FS). 1990a.Critique of meetingprocess and content.FuncA social impactanalysis begins with USDAFOISTSERVICE landmanagement planning: lOlume 1,Synthesis ofthe tional communities could also indicate selecting theimpacts or impactcatecritique oflandmanagement planning. USDAForest sitesfor meetings. gories to beanalyzed. Residents could Service FS-452. Washington, DC:USDAForest SerThe process we usedto identify develop impactcategories thatreflect vice,Policy Analysis Staff. ß1990b. Critique oflandmanagementplanntng functionalcommunities wastotally the issuesand concerns of their funclOlume 7, E•ctiveness of decisionmaking. USDAForineffective in reachingtheAmerican tionalcommunities, andsocial impacts estService FS-458. Washington, DC:USDAForest Indiansof northern Wisconsin, prob- couldbeevaluated separately for each Service, Policy Analysis Staff. ablybecause ourconcept did notfit a community; theanalysis donefor the . 1995.Social impact analysis: Principles andproNative world view. When we asked Tongass NationalForest planrevision cedures:Student manual USDA-Forest Service the few American Indians we were Course 1900-03ß Washington, DC: USDAForest isanexample (USDA-FS1996).FuncService, Ecosystem Managementß able to interview to define their comtionalcommunity focusgroups could ß1996.73ngass landmanagementplan revision-munities, theyidentified areas thatran alsohelpforestmanagers evaluate poRevised supplement tothedra•environmental impact from Thunder Bay to Sault Ste. tentialimpacts andanticipate therestatement. USDA Forest Service R10-MB-314a Marie, Ontario, and down into south- sponse of eachcommunity to theplan Washington, DC:USDAForest Service, Alaska Re- ern Wisconsin, Minnesota, and even alternatives. The evidence from our social assess- gion. SouthDakota.Their relationship to the landis determined by traditional menteffortindicates thatidentifying hunting,fishing,andgathering, and functional communities in and around theareas in whichtheypractice these nationalforestsis the first stepin PamelaJakes(e-mail:pjakes/nc@j5 activities is "home"--whatever the building a constructive relationship be- j•d.us)isproject leader, NorthCentral distance. Incorporating American In- tweenpubliclandmanagers andtheir Forest Experiment Station, St.Paul,MN dianperspectives intofunctionalcom- localcommunities--a stepthatcanul- 5510& ThomasFish is researchassistant, munities will take additional research. timatelycontribute to sustainable for- University ofMinnesota, St.Paul,' Deborah Carr is researchsocial scienttst, Finally,followupeffortsshouldas- estryandcommunities. sessthe applicabilityof functional North CentralForest Experiment Stacommunities to forestplanningto de- Literature Cited tion,EastLansing, Michigan; andDale terminewhatpartsof thecommunity BA•ER,D.M. 1981.Citizenpartia•ationinAmerican Blahnaisassociate pro•ssor, UtahState communities: Strategies fir successß Dubuque,IA: profiles aremostuseful andhowfuncUniversity, Logan. :36 March 1998