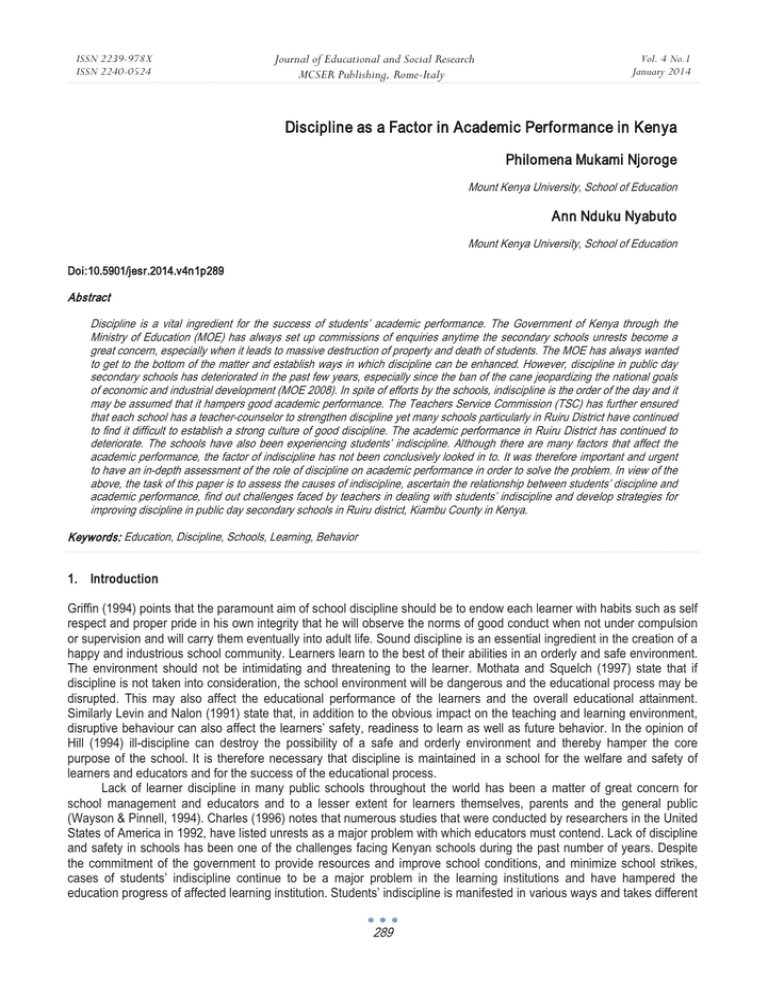

Discipline as a Factor in Academic Performance in Kenya

advertisement