The University of Montana Writing Center Annual Report AY 2010-2011

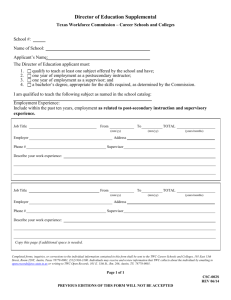

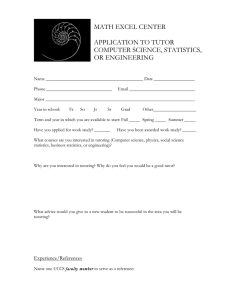

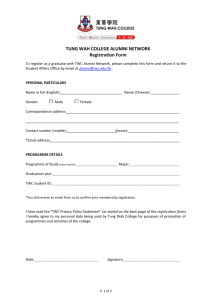

advertisement