Direct participation in hostilities INTERPRETIVE guIdaNcE oN ThE NoTIoN of

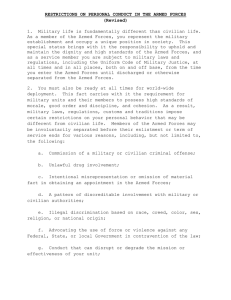

advertisement