Document 11914507

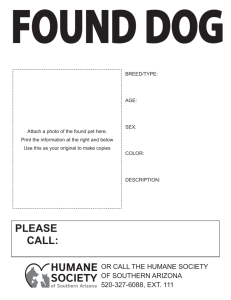

advertisement