Review of the Joint Programming Process Mrs. H. Acheson

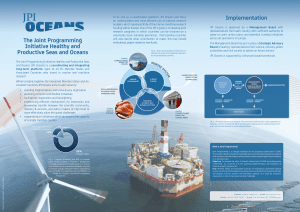

advertisement