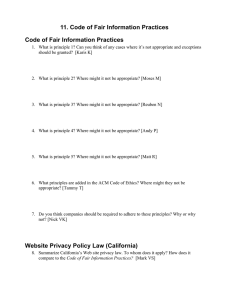

I ............................................................................... 487 I. B

advertisement