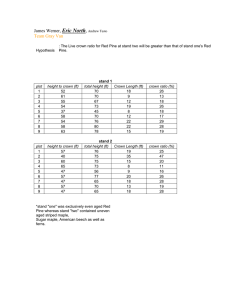

Fuel Reduction in Residential and Scenic Forests: a Comparison

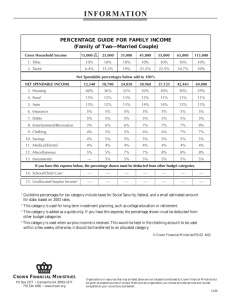

advertisement