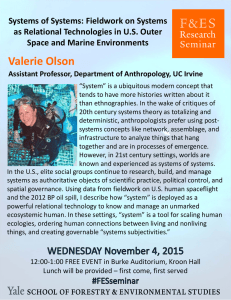

Organization Science

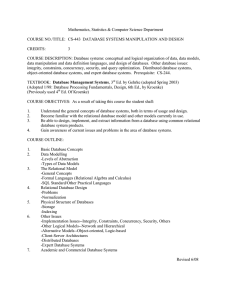

advertisement