Penstemon personatus on the Plumas National Forest

advertisement

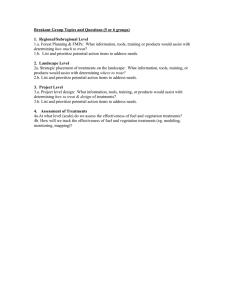

The effect of timber management activities on Penstemon personatus on the Plumas National Forest by Michelle Coppoletta, Kyle Merriam, Colin Dillingham, and Linnea Hanson Penstemon personatus (closed-throated beardtongue) is a rare species that is presently known from four counties in the northern portion of the Sierra Nevada mountain range (Figure 2). Most of the P. personatus occurrences (74 percent) are found within the boundary of the Plumas National Forest (NF) where this rhizomatous perennial occurs in 23 large but localized populations that vary in size from thousands of individuals to less than 10. P. personatus is currently designated as a Sensitive Figure 1. Penstemon personatus flower species by the USDA Forest Service (USDA Forest Service 2006). The California Native Plant Society lists P. personatus as a 1B.2 species, which indicates that it is fairly endangered in California (California Native Plant Society 2010). Based on this listing status, as well as the large number of populations on National Forest lands, it is imperative to ensure that management actions do not contribute to a loss of population viability or create a need for listing P. personatus as endangered or threatened under the Federal Endangered Species Act. Figure 2. Distribution of P. personatus 1 Past observations suggest that P. personatus may tolerate or even benefit from some timber management practices that reduce the forest canopy (Urie, Tausch and Hanson 1989, Hanson 1987). Monitoring data collected in the mid-1980s attempted to quantify the effects of timber harvest activities on P. personatus; however a comprehensive analysis of this data has never been completed. This paper presents the results of an analysis of frequency data collected between 1986 and 1995. The objective of this analysis was to determine the effects of different types of timber harvest activities on P. personatus frequency. To frame our analysis, we focused on the following questions: 1. Do timber harvest treatments result in a decline in P. personatus frequency? 2. If so, are some treatments more likely to cause a decline than others? 3. If treatments do have an effect on P. personatus, how long do the effects of the treatments last? Do occurrences rebound over time? Methodology In the late 1980’s, Plumas NF staff established 29 permanent transects within P. personatus occurrences to measure the species’ response to timber harvest activities. Presence/absence data were collected in milacre quadrats (43.56 ft2), which were placed along transects at 50 foot intervals. These data were used to calculate the frequency of P. personatus, which was determined by calculating the total percentage of quadrats that contained at least one rooted individual. With the exception of two control units, all of the units were treated with one of the following prescriptions (Figure 3): Mechanical thinning (n=3): selective removal of trees Overstory removal (n=17): selective removal of trees in the upper canopy Shelterwood harvesting (n=3): removal of most trees in the unit, leaving only those trees necessary to produce sufficient shade for regeneration Clearcutting (n=4): removal of essentially all trees 2 Figure 3. Photographs illustrating the types of treatments analyzed: (a) shelterwood harvest (Phillip McDonald USDA Forest Service); (b) mechanical thinning; (c) clearcut (Raumann and Soulard 2007); and (d) a P. personatus control area on the Plumas NF. For our analysis, we grouped the treatments into three categories: control (no treatment); moderate intensity (mechanical thinning and overstory removal); and high intensity (shelterwood harvesting and clearcutting). We also focused our analysis on data collected within the first five years following treatment. A repeated measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted to analyze the effect of the three different treatment categories on P. personatus frequency within the first five years following treatment. The change in frequency was calculated for each transect by comparing pre and post-frequency values over three time periods: (a) 1-2 years after treatment, (b) 3-4 years after treatment, and (c) 5 years after treatment. For the control units, the change in frequency was calculated using the first measurement value for comparison, rather than a pre-treatment value. Plots with missing values at any of the three time periods were excluded from the analysis. 3 Results and Discussion Do timber harvest treatments result in a decline in P. personatus frequency? If so, are some treatments more likely to cause a decline than others? The change in P. personatus frequency was significantly different across the three treatment types (α=0.5; p=0.03). This difference was due to the significant decline of P. personatus frequency within the high intensity treatment units, which decreased from their pre-treatment values by an average of 36 percent over the five years following treatment (Figure 4). The change in frequency in the moderate intensity treatment units was not significantly different than the control units; this result is consistent with past observations, which suggest that P. personatus is able to tolerate or even benefit from low to moderate intensity timber harvest activities (Hanson 1987, Hillaire 2001). * * * Figure 4. Change in P. personatus frequency over time in response to the three different treatment types. Error bars represent standard error. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences between treatments. Past monitoring has demonstrated that P. personatus is able to tolerate a wide range of canopy and light conditions. While P. personatus does occur in areas with moderate to dense overstory canopy, some studies have shown that open canopy conditions, such as those found in clearcuts, can promote flowering and growth of individuals (Urie et al. 1989). This suggests that the 4 decrease in P. personatus frequency within the high intensity treatment units is probably not due to changes in overstory canopy alone. Hanson (1987) observed that P. personatus appears intolerant of activities that result in high levels of ground disturbance. High intensity treatments, such as clearcutting and shelterwood harvest, typically result in higher levels of ground disturbance than the more moderate treatments (i.e. mechanical thinning and overstory removal) and have the highest probability for direct impact to individual plants. These disturbance factors, either alone or in combination with the removal of overstory canopy, may contribute to the observed decline in P. personatus following high intensity treatments. How long do the effects of the treatments last? Do occurrences rebound over time? P. personatus frequency declined significantly (α=0.5; p=0.01) within the first two years following treatment, regardless of the treatment type (Figure 5). This result is not surprising considering that plants could be directly impacted by equipment during treatment implementation or indirectly affected by changing light conditions. These impacts would result in an initial decline in plant frequency; however because P. personatus is rhizomatous, it is most likely able to recover to pre-treatment levels by re-sprouting a few years after treatment. Figure 5. The effect of time since treatment on P. personatus frequency. Error bars represent standard error. Note that the only value that is significantly different from zero is the change in frequency 1-2 years after treatment. 5 The results presented in Figure 5 correspond with observations made by past researchers. For example, Zebell et al. (1991) and Dwerlkotte (1990) both reported that P. personatus frequency tended to drop in the first year after logging and then rebound in year three to pre-logging levels. There was no significant interaction between the treatments and time, which indicates that differences between the treatments (Figure 4) were not dependent upon the measurement year. Conclusions High intensity treatments, such as clearcutting and shelterwood harvest, resulted in a significant decline in P. personatus frequency. Moderate intensity treatments, such as mechanical thinning and overstory removal, did not result in a significant decline in P. personatus frequency. P. personatus frequency is most likely to decline in the first year or two following treatment; however it may rebound after year three to pre-treatment levels. Management Recommendations Consider protecting a portion of P. personatus occurrences within high intensity treatments. Large clearcuts and overstory removal treatments are not as commonplace as they once were on the Plumas NF; however current management activities such as group selection harvests, which remove almost all of the trees within small (0.5-2 acre) units, could be considered high intensity harvest treatments. When planning group selection treatments, which have the potential for large amounts of soil disturbance and direct impacts to individuals, managers may want to ensure that a portion of the P. personatus occurrence is protected from direct impacts. Include density or cover measurements in any future frequency monitoring efforts. While the results of these analyses contribute to our understanding of the response of P. personatus to timber harvest activities, it is important to note that the only response factor measured in this monitoring effort was frequency. Frequency provides some insight into how treatments affect the distribution of P. personatus within a site; however frequency data alone do not provide information on other relevant biological indicators, such as plant abundance. While this design is relatively quick and easy to implement in the field, and is often recommended for rhizomatous plants such as P. personatus (Elzinga, Salzer and Willoughby 1998), frequency can often be difficult to interpret biologically. In some cases, the number of individuals within populations can be declining, while the distribution of plants across the landscape remains the same (Donohue 1994). One example of this is P. personatus frequency data collected for the Hardquartz project on the Plumas NF. In 1984, the population estimate was at its highest (2,336 individuals), 6 while frequency was estimated as 63 percent (Donohue 1994). Five years later, the population dropped to 577 individuals, while the frequency increased to 65 percent (Donohue 1994). If utilized further, frequency monitoring should be paired with density or cover measurements (Donohue 1994). Incorporating these additional variables will provide for a broader understanding of the effects of treatment activities on both the distribution and abundance of P. personatus. References California Native Plant Society. 2010. Inventory of Rare and Endangered Plants. February 11, 2010). Donohue, B. L. 1994. Review of rare plant monitoring efforts on the Plumas National Forest, USDA Pacific Southwest Region. 26 pages. Dwerlkotte, R. 1990. 1990 Penstemon personatus monitoring summary for the Quincy Ranger District. USDA Forest Service, Plumas National Forest. Elzinga, C. L., D. W. Salzer & J. W. Willoughby. 1998. Measuring and Monitoring Plant Populations. BLM Technical Reference 1730-1, Denver, Colorado. Hanson, L. 1987. Species Management Guide for Penstemon persontaus. USDA Forest Service, Plumas National Forest. Hillaire, S. 2001. Habitat requirements of closed-throated beardtounge (Penstemon personatus Keck.), and response after logging, including affects of KV activities and temporal changes (1988-2001). USDA Forest Service, Plumas National Forest. McDonald, P. Shelterwood cut in the Challeuge Experimental Forest in the northern Sierra Nevada's. In www.forestryimages.org, ed. 4799088. USDA Forest Service. Raumann, C. G. & C. E. Soulard. 2007. Land-cover trends of the Sierra Nevada Ecoregion, 1973-2000: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 20075011 In http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2007/5011/. Urie, S., R. Tausch & L. Hanson. 1989. A Statistical Analysis of Penstemon personatus. USDA Forest Service, Plumas NF. USDA Forest Service. 2006. 2006 Sensitive Plant List, Pacific Southwest Region, Region 5. Letter from Regional Forester Weingardt. File Code: 2670. Dated July 27, 2006. Zebell, R., B. Castro & R. Dwerlkotte. 1991. Penstemon personatus frequency monitoring, 19801990 -- Summary. USDA Forest Service, Plumas National Forest. 7