Document 11875452

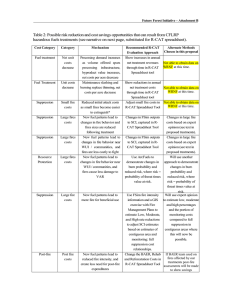

advertisement

United States Department of Agriculture File Code: Route To: Subject: To: Forest Service Plumas National Forest 159 Lawrence Street P.O. Box 11500 Quincy, CA 95971-6025 (530) 534-7984 Text (TDD) (530) 283-2050 Voice Date: January 17, 2007 FY 2006 Progress Report on HFQLG Pilot Project Monitoring Effects of the Pilot Project on Air Quality Colin Dillingham, HFQLG Monitoring Coordinator Question 9) Were provisions of the Smoke Management Plan implemented? The objective is to see if burns meet the provisions of Smoke Management Plans (SMP) as defined in the California Air Resources Board Title 17 and the EPA’s Interim Air Quality Policy. The monitoring protocol is to conduct post-burn evaluations to assess adherence to SMP provisions for all burns. In 2006 there was one violation of the SMP that covered pile burning on the Beckwourth District, Plumas NF. A “Notice to Comply” was issued that cited two items in the SMP that covered the Mabie project that were not followed; 1) the piles were allowed to creep, so they did not meet the requirement that piles completely burn within 24 hours and 2) burning should create little or no impact on surrounding residents, businesses or persons. No Class I Airsheds were impacted; however there were seven days that Smoke Sensitive Areas (communities) were impacted by smoke from adjacent burns. The Forest Service received seven smoke complaints; three of the complaints were based on health related issues. Question 26) Do prescribed fire activities meet air quality standards? The objective is to meet provisions of the SMP and air quality standards. The monitoring protocol is to assess adherence to Smoke Management Plan provisions for all burns. Utilize data from Air Quality Management District (AQMD) recorders and/or portable recorders to assess impacts to air quality at receptor sites. An air quality monitor located in the City of Portola recorded that National Ambient Air Quality Standards were exceeded for particulate matter 2.5 microns in size (PM 2.5) during four days in December that could partially be attributed to piles that continued to creep after ignition on the Mabie project. Question 27) Do prescribed fires create a nuisance in terms of air quality? The objective of this monitoring question is to limit or reduce the number of prescribed burns discontinued due to complaints. The monitoring protocol is to log the number of complaints (date, time, telephone number, address and type of impact) and track the number of projects discontinued due to complaints about air quality resulting from prescribed burns. Approximately 5,900 acres in HFQLG projects were burned in 2006 and 7 complaints were filed, 2 of the 7 complaints were from Portola and associated with the Mabie pile burning, these 2 complaints resulted in not burning on 20 “Permissive Burn Days” due to local concern of smoke impacts. The six Districts that conducted burning in HFQLG projects, reported a total of 153 days of burning. This number of burn days however is overstated, because it was reported as number of day’s per/project, and it is common to be burning on a number of different projects on one day. Caring for the Land and Serving People Printed on Recycled Paper Year 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 Forest Reporting Plumas Plumas All All All Acres Burned Number of Burn Days Number of Complaints 5,045 4,280 10,778 14,310 5,863 66 67 164 210 153 3 0 0 16 7 “Permissive Burn Days” that no burning took place due to Air Quality Concerns 1 0 0 4 22 This table summarizes information collected to see if any trends are apparent. To date information is not gathered that looks at the distance between burn projects and populated areas. However, looking at the Plumas NF information only, when planning underburns in the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI), the forest should make additional efforts to notify neighbors, businesses, and other interested parties of the need for underburn treatments and what to expect in terms of smoke production when the burns are implemented. Since the National Fire Plan emphasizes fuel reduction in the wildland urban interface, education and notification of prescribed burn activities is essential and should limit the number of people that consider smoke a nuisance when burning is necessary. Fuels personnel working on several districts within the HFQLG Pilot Project area noted that dedicated efforts to communicate with the community about burn projects prior to their implementation likely resulted in decreased complaints and better overall public relations. Coordination with the Northeast Air Alliance and neighboring forests is now standard protocol during prescribed burn season. During 2006 the land managers that conduct burning within the Northeast Air Alliance area (which the Pilot Project is part of) have followed the operating guidelines that were produced last January in an effort to reduce the likelihood of wide spread cumulative smoke impacts like those that occurred in October of 2005. The Northeast Air Alliance noted success of this program in during the winter, 2007 Northeast Air Alliance Meeting. Although the same favorable burning conditions did not develop this year as they did in 2005, these procedures may have reduced the potential for cumulative impacts with at least one situation (Almanor District deferred one burn due to plans on adjacent units). In an effort to minimize air quality impacts to populated areas the Northeast Air Alliance (NEAA) developed a “Pre-Burn Communication Operating Plan” last winter. The operating plan was followed for two burn seasons since its development and will likely minimize occurrence of cumulative smoke impacts within the Pilot Project area. One component of the operating plan that has not been fully developed on the Plumas, Tahoe and Lassen National Forests is the Public Education and Awareness Strategy. Currently, each District progressively notifies and educates the public on a project-by-project basis, but the Forests have not yet achieved the full vision fire managers feel is possible. Action Item 1 – Forest Public Information Officers should work with fire managers to develop a strategy as outlined in the NEAA operating plan. Every under burn should be seen as an opportunity to help the public understand why a fuel treatment is being implemented; these opportunities give the agency a chance to listen to concerns and adapt practices where feasible. Several districts within the HFQLG Pilot Project Area have reported that making direct contact with the public via phone, personal visits, posters, and the newspaper for specific burn projects has helped limit the number of complaints and provided an excellent informal forum for public education. Fuels personnel noted that in addition to general newspaper and flyer notifications, it was important to identify and contact individual members of the public who may have concerns about a specific underburn project. In particular, these members of the public include businesses or event coordinators who expect clear skies at the time of their event, persons who have expressed concerns about smoke in the past, have personal health concerns, or who are responsible for the care of someone who may be sensitive to increased exposure to smoke. Public meetings focused on planned under burns have had limited attendance; it may be better to focus efforts on contacting neighbors by phone, door-todoor, and, if necessary, post a Public Information Officer in a visible location near the under burn itself while it is being implemented. It has been suggested that a brochure be developed for the fuel treatment/prescribed fire program. One example of a prescribed fire education brochure is included with this report. Action Item 2– Explore other methods of biomass removal and disposal in the WUI • • • Green fire wood sales focused on small material in the WUI. Encourage small scale biomass chipping and hauling operations Work with the City of Portola and the Northern Sierra Management District to analyze benefits of an air current burner for use in Sierra Valley. Explore options for small, community level biomass plants through the USDA “Fuels for Schools” (http://www.fuelsforschools.org/) or similar program. An attachment is provided that shows type of burning by project in 2006. LOU ANN CHARBONNIER Fuels Officer JASON MOGHADDAS Fire Ecologist United States Department of Agriculture File Code: Route To: Subject: To: Forest Service Plumas National Forest 159 Lawrence Street P.O. Box 11500 Quincy, CA 95971-6025 (530) 534-7984 Text (TDD) (530) 283-2050 Voice Date: November 17, 2006 FY 2006 Progress Report on HFQLG Pilot Project Monitoring Effects of the Pilot Project on Wildland Fire Colin Dillingham, HFQLG Monitoring Coordinator The following monitoring questions relate to what effect the vegetation management activities authorized under the HFQLG-FRA have on wildland fire. Question 23: What is the trend in large fire frequency? Question 24: What is the trend in severity of large fires on acres burned? Question 25: What is the effect of treatments on fire behavior and suppression? Overview – Two of these three questions would be best answered after at least 25 years from the time the Pilot Project has been completed. The third question on the effectiveness of treatments on fire behavior and suppression should be evaluated each time a wildland fire is influenced by one of the vegetation management activities authorized by the HFQLG-FRA. Status and Suggestions: Question 23: What is the trend in large fire frequency? All fires greater than 10 acres exist on a GIS layer that is updated on an annual basis. In 2036, all fires greater than 100 acres that occurred from 1985-2010 should be compared to fires greater than 100 acres that occurred from 2011 to 2036. This analysis should also include analysis of weather and suppression resources for the same time periods. Most likely it will be necessary to contract this analysis. Question 24: What is the trend in severity of large fires on acres burned? In 1999 the Region began the Landscape Level Fire Monitoring program that will quantify the number of acres burned at different severity levels by fire and vegetation types. In addition to mapping severity of all fires greater than 1,000 acres, the Regional program also mapped severity for all fires greater than 100 acres from 1984 to 1999 for certain areas in the Sierra Nevada’s. The Adaptive Management Services Enterprise Team published a Draft report on this “Sierra Nevada Fire Severity Monitoring 1984-2004”, in April of 2006. This report contains analysis of nine fires that have occurred within the Pilot Project area and should be utilized when this question is ultimately answered. In addition, Kyle Merriam the Province Fire Ecologist has begun documenting the effects of fire severity and fuels treatment on the Boulder Fire (Plumas NF, 2006), which will become part of the Pilot Project record when complete. Question 25: What is the effect of treatments on fire behavior and suppression? Within the Pilot Project area the Dow Fire (Eagle Lake Ranger District, Lassen National Forest, 1999), Cone Fire (Blacks Experimental Forest, Lassen National Forest, 2002) and the Stream Fire (Mt Hough Ranger District, Plumas National Forest, 2001) have all been referenced in prior years to address this question and the reports are part of the Pilot Project Record. Caring for the Land and Serving People Printed on Recycled Paper In October of 2006, Jason Moghaddas, Pete Duncan and Scott Abrams (Mt Hough District, Plumas National Forest) completed a report on the effects fuel treatment had on suppression efforts on the Boulder and Hungry fires that occurred in June of 2006. This report is part of the Pilot Project record. The following is the summary from the report. Overall, fuel treatments in the Boulder Complex met stated Purpose and Need of reducing probability of future crown fire and high severity surface fire. Fuel treatments which were exposed to extreme winds (>20 MPH) during on June 26th did incur high mortality (>75 % of basal area killed). This result is not unusual considering that gusting windspeeds greatly exceeded design windspeeds on June 26th and 27th. In addition, an extreme amount of radiant heat was blown towards the fuel treatment from adjacent untreated areas as they burned, resulting in increased severity within fuel treatments. Driving along road on the east side of Antelope Lake, one can clearly see areas of high severity (>75% basal area killed) in untreated stands immediately adjacent to areas of low to moderate severity in treated stands. With respect to suppression actions, fuel treatments along the Wemple Cabin Road allowed for a safe implementation of a low severity burnout operation. The Hungry Underburn allowed for relatively easy containment of the south edge of the Hungry Fire using fewer resources. The portions of the Boulder Fire burning within the Hallet underburn were relatively easy to contain with limited resources due to low (<3 foot) flame lengths. In these areas, the fuel treatments improved suppression efficiency as stated in the HFQLG-EIS, Appendix J (USDA 1999). The Type II Team assigned to the Boulder Complex had local knowledge of existing fuel treatments. This knowledge facilitated the use of these treatments for suppression tactics. This underscores the need for districts to be able to quickly provide GIS based, updated spatial information about fuel treatment locations to incoming fire teams so that the treatments may be used more efficiently to contain fires, potentially reducing overall fire severity and suppression costs. At this time there is no formal monitoring protocol established to study the effectiveness of fuel treatment and fire behavior. I suggest each Forest in the Pilot Project area request the Rapid Response Fire Team (AMSET) to conduct real time monitoring any time a fire that exceeds the complexity of a type 3 incident and has the potential to burn any vegetation management activities implemented as part of the HFQLG-FRA. Additionally, I recommend that a protocol similar to that developed by the Rocky Mountain Area Coordinating Group be used to evaluate effectiveness of treatments on smaller fires. LOU ANN CHARBONNIER Fuels Officer CC: Mike Holmes Gary Fildes Kyle Merriam Allan Setzer Jason Moghaddas Scott Abrams Pete Duncan 2006 Key Points Fire/Fuels and Air Quality Three wildland fires that burned in 1999 (Dow Fire), 2001(Stream Fire) and 2002 (Cone Fire) have been previously reported as burning at lower fire intensities when they burned into fuel reduction areas similar to those being implemented under the HFQLG Forest Recovery Act. Benefits noted from these fires burning at lower intensities were reduced mortality within the treated stands and improved suppression opportunities. In 2006 the presence of recently completed Defensible Fuel Profile Zones (DFPZs) aided in the suppression efforts of both the Boulder and Hungry Fires again due to lower fire intensities within the treated DFPZs. Since the beginning of the Pilot Project the Plumas National Forest received two notices for non-compliance with air quality regulations while implementing HFQLG fuel reduction projects. A Notice of Violation was issued for the underburning on the Greenflat project and was reported in last years monitoring report. The Greenflat project was not within the wildland urban interface (WUI), the air quality impacts to communities was a result of accumulation of smoke from a number of prescribed burns being conducted on the Plumas, Lassen and Tahoe National Forests as well as the Lassen National Park. A Notice to Comply was issued for handpile burning on the Mabie project that lies within the WUI areas of Sierra Valley. Smoke from the pile burning in addition to residential burning and wood stoves lead to an exceedance of the National Ambient Air Quality Standards for PM 2.5. In an effort to minimize air quality impacts to populated areas the Northeast Air Alliance (NEAA) developed a “Pre-Burn Communication Operating Plan” last winter. The operating plan was followed for two burn seasons since its development and will likely minimize occurrence of cumulative smoke impacts within the Pilot Project area. One component of the operating plan that has not been fully developed on the Plumas, Tahoe and Lassen National Forests is the Public Education and Awareness Strategy. Currently, each District progressively notifies and educates the public on a project-by-project basis, but the Forests have not yet achieved the full vision fire managers feel is possible. Action Item 1 – Forest Public Information Officers should work with fire managers to develop a strategy as outlined in the NEAA operating plan. Every under burn should be seen as an opportunity to help the public understand why a fuel treatment is being implemented; these opportunities give the agency a chance to listen to concerns and adapt practices where feasible. Several districts within the HFQLG Pilot Project Area have reported that making direct contact with the public via phone, personal visits, posters, and the newspaper for specific burn projects has helped limit the number of complaints and provided an excellent informal forum for public education. Fuels personnel noted that in addition to general newspaper and flyer notifications, it was important to identify and contact individual members of the public who may have concerns about a specific underburn project. In particular, these members of the public include businesses or event coordinators who expect clear skies at the time of their event, persons who have expressed concerns about smoke in the past, have personal health concerns, or who are responsible for the care of someone who may be sensitive to increased exposure to smoke. Public meetings focused on planned under burns have had limited attendance; it may be better to focus efforts on contacting neighbors by phone, door-to-door, and, if necessary, post a Public Information Officer in a visible location near the under burn itself while it is being implemented. It has been suggested that a brochure be developed for the fuel treatment/prescribed fire program. One example of a prescribed fire education brochure is included with this report. Action Item 2– Explore other methods of biomass removal and disposal in the WUI • • • • Green fire wood sales focused on small material in the WUI. Encourage small scale biomass chipping and hauling operations Work with the City of Portola and the Northern Sierra Management District to analyze benefits of an air current burner for use in Sierra Valley. Explore options for small, community level biomass plants through the USDA “Fuels for Schools” (http://www.fuelsforschools.org/) or similar program. HFQLG Project Type of Burn (Piles Burner (FS or or Underburn?) Contractor) Humbug Crystal/Adams Last Chance District Piles Red Clover BCK Totals Hand piles Hand piles UB Hand/Machine piles UB Contract Contract Contract FS FS Hungry Deanes piles Guard piles PG&E Piles Mt. Hough Piles Dancehouse piles MTH Totals Brush Creek DFPZ Brush Creek DFPZ FRD Totals Underburn Piles Piles Piles Piles Piles FS FS FS FS FS FS UB Pile Firestorm FS Underburn Underburn Underburn Piles FS FS FS FS Underburn FS Plumas Totals Wiley - HC Blacks Ridge-HC Pittville-HC DFPZ Handpiles-HC Hat Creek Totals Eagle Lake Totals Warner-ALM Almanor Totals No HFQLG burning Lassen Totals Various(WFHF) Zingira RX Borda RX S'Ville Totals Pilot Project Totals MP,HP UB UB FS FS FS Total Acres Burned 2006 Number of Days Impact to Class I Impacted Smoke Airsheds (Yes or No) Sensitive Area1 Number of Days Burned Number of Complaints2 Type of Complaint3 Number of Days Number of Days Exceeded National Shut down by AQMD and/or State Ambient Air Quality Standards 0 0 0 0 0 0 20 2 0 0 20 2 216 480 656 702 203 2,257 12 10 20 20 10 72 No No No No No 0 0 1 4 0 5 0 0 1 1 0 2 265 15 15 3 1 1 300 55 10 65 5 1 1 1 1 1 10 2 1 3 No No No No No No 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 2,622 85 120 298 959 300 1,677 2 3 6 3 14 0 0 245 245 4 4 1,922 18 505 522 292 1,319 30 10 10 50 5,863 153 No No health health 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 2 21 2 No No No No 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 No 2 2 4 4 2 No No No Percent Compliance with SMP Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 Yes Yes Yes 7 7 22 2 95% Health/annoyed Smoke Yes Boulder Complex Fire Behavior, Suppression Action, and Severity Jason Moghaddas, Fire Ecologist Scott Abrams, Battalion 25 Pete Duncan, Battalion 24 Mt Hough Ranger District, Plumas National Forest 10/10/2006 • Scope of this Brief: This brief provides a preliminary assessment of overall fire severity within fuel treatments and in un-treated areas on the Boulder Complex. Secondly, this brief provides preliminary documentation of how fuel treatments were used for suppression actions. The discussion in this brief focuses primarily on the “Boulder” and “Hungry” fires. The other fires within the Boulder Complex were relatively small and were not directly affected by fuel treatments. Information in this brief is taken from the Boulder Complex Incident Narrative (Norcal Team 1, 2006), the Boulder Complex Burned Area Emergency Response Report (BAER Report 2500-8), as well as interviews with on scene fire management personnel. It is important to note that extreme local wind conditions experienced on the Boulder Fire exceeded 20 miles per hour for at least two days. These wind speeds exceeded the design 90th percentile windspeeds of ~10 miles per hour. The Boulder Complex will be further analyzed using updated fire severity maps as part of a separate study. • Antelope Project Purpose and Need (USDA 2000) 1. Reduce the Probability of future crown fires by using thinning and prescribed burning to remove at least 90% of fuel ladders 2. Reduce the potential spread of crown fires by reducing canopy cover to 40% 3. Reduce potential for high severity surface fire 4. Contribute to economic stability of rural communities by generating economic activity, income, and employment 5. Implement the Record of Decision for the HFQLG-FRA EIS In addition, the HFQLG EIS, Appendix J, (USDA 1999) states that within fuel treatments: “Suppression efficiency would be improved under this strategy by creating an environment where wildfires would burn at lower intensities and where fire fighting production rates would be increased because less ground fuels and small diameter trees would need to be cleared for fireline construction or backfiring (removing the fuels under controlled burning conditions prior to the wildfire reaching the DFPZ). Aerial retardant application would also be more efficient under this strategy because the open canopy would allow the retardant to penetrate and be more effective at slowing fire spread in the light surface fuels.” • Overall Fire Behavior and Severity The Boulder Fire origin was near a ridgeline above the headwaters of the north branch of Lost Creek. On June 25th, thunder cells moving though the Antelope Lake Area causing erratic, strong winds. These winds pushed the fire down slope for 1.8 miles towards Antelope Lake in 40 minutes (>200 chains per hour). Over the next few days (6/26, 6/27) gusting winds were reported over 20 miles per hour on the Boulder Fire and at the Pierce R.A.W.S. Station. During these wind events, flame lengths exceeding 5 feet along with torching and long distance spotting were reported. Crews could not attempt direct suppression actions during these high wind events. Areas burned under these windy conditions had high mortality (>75% mortality) of conifers. Based on observations during and after the fire, flame lengths and fire intensity were lower within the Antelope Fuel Break on the Boulder Fire. High resolution burn severity maps show greater than 90% mortality within fuel treatments between the northern edge of the fuel treatments to the intersection with road 27N19Y. Initial post burn reconnaissance confirmed high mortality in this portion of the area, though dead needles are still attached to the limbs. In the adjacent untreated area, immediately east of the treatment boundary, needles are “blown off” limbs, indicating a much higher intensity fire in this area. Within the Antelope fuel treatment south of road 27N20Y, severity is relatively lower (10-50%) than adjacent untreated areas that burned with high severity (>75%). The Border Fuel Treatments along the Wemple Cabin road (27N60) were used for a burn out operation. During this burnout (see discussion on effects of treatments on suppression actions, 900 acres were burned using a backing fire over a 3 day period (07/01/2006-07/04/2006). Within the burnout area, fire severity was approximately 70% low and 30% moderate or high. The burnout area was used to contain the south and southeastern flanks of the Boulder fire. The northern edge of the fire impacted the Hallet Project (overstory removal and underburned- completed in 1999). The main fire impacted the Hallet Project as a crown fire, but due to previous treatments, specifically underburning, the fire behavior transitioned to a low intensity ground fire. Within this area, flame lengths were generally less than 3 feet with a relatively low rate of spread and easily contained by fire fighters. On the Hungry Fire, similar weather conditions occurred as described for the Boulder Fire as these fires burned simultaneously. Most notably, on the Hungry Fire, the Hungry Underburn, which was completed 06/04/2006 (last patrol date 06/22/2006) was used to hold the southern edge of the Hungry Fire. 2 It is important to note that extreme local wind conditions experienced on the Boulder Fire were outside the typical 90th percentile windspeeds of ~10 miles per hour. Even with extreme winds, and based on initial assessments, the fuel treatments in the Boulder and Hungry fires did the following: 1) Reduced fire severity, particularly along the Antelope Lake Road south of Road 27N19Y 2) Increased needle retention in treated areas burned under high severity when compared with untreated areas. These needles have already begun to fall and provide ground cover. 3) Enhanced opportunity for conducting a safe, low severity burnout along Wimple Cabin Road with decreased chances of torching and spotting. 4) The Hallet Project was ignited by the Boulder Fire, though containment in this area was relatively easy due transition from a crown fire and low (<3 feet) flame lengths. 5) The Hungry Underburn was used to safely contain the southern edge of the Hungry Fire 6) Created conditions where flame lengths remained below 4 feet in some areas, allowing direct suppression action by hand crews. • Influence of Fuel Treatments on Fire Suppression Activities Antelope Border DFPZ: Used for burnout along Wemple Cabin Road Once fire was established in the Antelope Creek drainage, steep and rocky terrain made it difficult to build direct fireline. The fact that the DFPZ along the 27N60 Road was in place and completed (to the extent permitted by existing guidelines) allowed for flexibility in planning suppression actions. The fire team elected to use indirect suppression methods, along the road and fire out the line. This provided firefighters with a safer environment in which to work. Using the road allowed for enhanced safety for firefighters and made it easier to identify, locate and suppress any spot fires, which resulted from the burnout operation. Having the DFPZ located on both sides of the road allowed fire fighters to more easily “hold” the top of the underburn. A few spot fires were ignited in the treated area above the underburn but were easily contained by fire fighters in the area. During the burnout, untreated riparian areas resulted in a slowing of burnout operations and had a greater amount of spotting and torching when compared with treated areas. The team had the decision space to work in, because of the DFPZ, to conduct the burnout operation under more benign environmental conditions. This reduced the spotfire probability, and increased the probability of the largest trees surviving. Since there was insufficient heat to get fire into the crowns of the larger trees, fewer embers crossed the 27N60 road, which was being used as the fireline. The lower surface fuel loading in the treated areas kept flame lengths low and manageable, and enabled suppression forces to conduct the burnout during a longer “window of opportunity”. 3 Antelope Border DFPZ Eastern Boundary: Used for control lines/contingency The Border DFPZ allowed for flexibility in choosing at which point the counter fire operation would turn down the hill towards the lake. Once this operation was completed, there was a complete firebreak around the fire. After one burning period, mop up was initiated, and the threat of fire spread was greatly reduced. A one-blade wide dozer fireline was constructed from the 60 Road down to the lake along a small spur ridge that was located in the area, treated in 2001 or 2002. Since this area had been thinned and underburned, it was safe and easy to construct the dozer line along the spur ridge. In addition, since the dozer line was located within the treated unit, if the fire had spotted across this relatively narrow line, there were a couple of areas, from which contingency lines could have been placed that also provided a safe environment. Hallet Project: 8-9 year old overstory removal and burn treatment (burned 1997): Used for handline construction The western portion of the Boulder Fire migrated into the old Hallet Project area. This project was an overstory removal followed by underburning and completed in the mid-90s. Although there was some regrowth of brush as well as places where mortality from the previous underburn had fallen to the forest floor, the fire behavior transitioned to a crown fire to a low intensity ground fire (flame length <3 feet with low rate of spread) to the extent that suppression crews were able to safely construct about a mile of direct handline from the top of the western flank of the fire down to the lower lake road. Had this area not been treated, the probability of the wildfire spotting across the Boulder Creek drainage and establishing itself on the south side of Wildcat Ridge would have greatly increased. Hungry Underburn Anchorpoint With regard to the Hungry Fire, a 237-acre underburn was completed just 3 weeks prior to the lightning fire. The treated unit was located southwest of the point of origin of the lightning fire. The Incident Commander was able to utilize the treated area as a safety zone and as a safe anchor point for suppression operations on the 650-acre wildfire. In addition, since such a large unit was previously treated, fewer firefighters and other resources were needed on a significant portion of the perimeter of the fire. Summary Overall, fuel treatments in the Boulder Complex met stated Purpose and Need of reducing probability of future crown fire and high severity surface fire. Fuel treatments which were exposed to extreme winds (>20 MPH) during on June 26th did incur high mortality (>75 % of basal area killed). This result is not unusual considering that gusting 4 windspeeds greatly exceeded design windspeeds on June 26th and 27th. In addition, an extreme amount of radiant heat was blown towards the fuel treatment from adjacent untreated areas as they burned, resulting in increased severity within fuel treatments. Driving along road on the east side of Antelope Lake, one can clearly see areas of high severity (>75% basal area killed) in untreated stands immediately adjacent to areas of low to moderate severity in treated stands. With respect to suppression actions, fuel treatments along the Wemple Cabin Road allowed for a safe implementation of a low severity burnout operation. The Hungry Underburn allowed for relatively easy containment of the south edge of the Hungry Fire using fewer resources. The portions of the Boulder Fire burning within the Hallet underburn were relatively easy to contain with limited resources due to low (<3 foot) flame lengths. In these areas, the fuel treatments improved suppression efficiency as stated in the HFQLG-EIS, Appendix J (USDA 1999). The Type II Team assigned to the Boulder Complex had local knowledge of existing fuel treatments. This knowledge facilitated the use of these treatments for suppression tactics. This underscores the need for districts to be able to quickly provide GIS based, updated spatial information about fuel treatment locations to incoming fire teams so that the treatments may be used more efficiently to contain fires, potentially reducing overall fire severity and suppression costs. References BAER (Burned Area Emergency Response) Report 2500-8. 2006. Boulder Complex Fire Initial 2500-8 Burned Area Response Report. Signed by Bernard Weingardt, Regional Forester, on July 14, 2006. Northern California ICT 1. 2006. Boulder Complex Incident Management Report. June 27-July 6, 2006. Incident Number CA-PNF-000371. USDA.1999. Herger-Feinstein Quincy Library Group Forest Recover Act: Final Environmental Impact Statement. Appendix J. Lassen, Plumas, & Tahoe National Forests. USDA. 2000. Antelope-Border Defensible Fuel Profile Zone. Environmental Assessment. Plumas National Forest, Mt Hough Ranger District. 5 PreventingFireW/Firefor WEB 7/6/99 11:26 AM Page 1 (1,1) Preventing Fire with Fire How do we do it? Fire has Three Faces that save: our wildlands our resources our selves... Our forests and grasslands are in danger. In many places, they are vulnerable to large destructive fires. Today we realize that fire has three faces: fire prevention Fire Prevention Fire Suppression Human carelessness will never be an acceptable cause of fire. We will always need to heed Smokey Bear. Wildfire threatens people, private property, watersheds, wildlife habitat, and our valued scenic and recreational resources. Smokey Bear educates children about preventing human caused fires. These fires must be - and are - put out. Home threatened by wildfire. Wildfire Our wildland firefighters’ goal is to protect life, natural and cultural resources, and property. fire suppression Thanks to our courageous men and women firefighters, loss of life and damage to property and resources from wildfires remain low. prescribed fire For most of this century our society viewed fire as an absolute enemy. We depended on our public wildland agencies to eliminate all fire from the environment. With the Three Faces of Fire Bureau of Land Management Oregon/Washington Forest Service Pacific Northwest Region But without low-intensity fires, some of our wildlands have grown overcrowded and explosive. Dead wood and dry brush cover the ground. Destructive insects and weeds invade. New growth is strangled and wildlife is threatened. Therefore, today, we understand fire’s vital ecological role. We realize the important interplay of these three faces of fire. Even so, our wildlands are now more vulnerable to large, destructive fires that destroy the life of our forests and grasslands and endanger communities. We must reduce the number of unplanned, destructive wildfires. Today, with more people building homes in wildlands, fire prevention efforts are even more critical. When natural or human caused fires ignite and spread, these homes - and people’s lives - are in harms way. There is a solution: Prescribed Fire... Firefighters put out grassland fire. PreventingFireW/Firefor WEB 7/6/99 11:27 AM Preventing Fire with Fire How do we do it? Page 1 (2,1) Fire has Three Faces that save: our wildlands our resources our selves... Our forests and grasslands are in danger. In many places, they are vulnerable to large destructive fires. Today we realize that fire has three faces: fire prevention Fire Prevention Fire Suppression Human carelessness will never be an acceptable cause of fire. We will always need to heed Smokey Bear. Wildfire threatens people, private property, watersheds, wildlife habitat, and our valued scenic and recreational resources. Smokey Bear educates children about preventing human caused fires. These fires must be - and are - put out. Home threatened by wildfire. Wildfire Our wildland firefighters’ goal is to protect life, natural and cultural resources, and property. fire suppression Thanks to our courageous men and women firefighters, loss of life and damage to property and resources from wildfires remain low. prescribed fire For most of this century our society viewed fire as an absolute enemy. We depended on our public wildland agencies to eliminate all fire from the environment. With the Three Faces of Fire Bureau of Land Management Oregon/Washington Forest Service Pacific Northwest Region But without low-intensity fires, some of our wildlands have grown overcrowded and explosive. Dead wood and dry brush cover the ground. Destructive insects and weeds invade. New growth is strangled and wildlife is threatened. Therefore, today, we understand fire’s vital ecological role. We realize the important interplay of these three faces of fire. Even so, our wildlands are now more vulnerable to large, destructive fires that destroy the life of our forests and grasslands and endanger communities. We must reduce the number of unplanned, destructive wildfires. Today, with more people building homes in wildlands, fire prevention efforts are even more critical. When natural or human caused fires ignite and spread, these homes - and people’s lives - are in harms way. There is a solution: Prescribed Fire... Firefighters put out grassland fire. PreventingFireW/Firefor WEB 7/6/99 11:29 AM Page 2 (1,1) Before Prescribed Fire Prescribed Fire For decades our land managers have used this “face of fire” to restore our wildlands to their balanced health. With prescribed fire, low-intensity flame is applied by trained experts to clear ground of dangerous fuels like dead wood and brush. Or, if a natural fire starts with conditions that are exactly right, and there is an environmental plan in place - experts can treat it as a prescribed fire. • Decades of dead wood buildups threaten the forest • Combustible materials could trigger large, destructive wildfires • Unplanned fire could endanger resources and human safety Low-intensity fire. • After prescribed fire has done its work. This low-intensity fire is vital to the life cycles of our forests and grasslands. There’s no question that prescribed fire can save wildlands and resources. Prescribed fire is just one tool we have to help restore balance to our ecosystems. It is a very effective tool and occurs only under prescribed environmental conditions. Here’s what you can do: • Learn more about your forests and grasslands. • Discuss the issues of prescribed fire with your family and friends. • Contact your local U.S. Forest Service or Bureau of Land Management office if you have questions. Field Offices are listed under U.S. Government in your local phone book or visit our website(s): After Prescribed Fire Use of driptorch to start prescribed fire. Yes, fire has many faces. It is a natural and vital element in our forests and grasslands. Through our wise use of fire we will realize a future where fire plays a necessary role in our wildlands’ cycle of life. Planned low-intensity fire has removed dangerous dead wood buildups • Forest retains its natural health • Threat of intense and harmful wildfire is gone • Forest Service - www.fs.fed.us/r6 • Bureau of Land Management www.or.blm.gov Native plants return quickly after fire. PreventingFireW/Firefor WEB 7/6/99 11:30 AM Page 2 (2,1) Before Prescribed Fire Prescribed Fire For decades our land managers have used this “face of fire” to restore our wildands to their balanced health. With prescribed fire, low-intensity flame is pplied by trained experts to clear ground of angerous fuels like dead wood and brush. Or, if natural fire starts with conditions that are xactly right, and there is an environmental plan n place - experts can treat it as a prescribed fire. • Decades of dead wood buildups threaten the forest • Combustible materials could trigger large, destructive wildfires • Unplanned fire could endanger resources and human safety Low-intensity fire. • After prescribed fire has done its work. This low-intensity fire is vital to the life cycles of our forests and grasslands. There’s no question that prescribed fire can save wildlands and resources. Prescribed fire is just one tool we have to help restore balance to our ecosystems. It is a very effective tool and occurs only under prescribed environmental conditions. Here’s what you can do: • Learn more about your forests and grasslands. • Discuss the issues of prescribed fire with your family and friends. • Contact your local U.S. Forest Service or Bureau of Land Management office if you have questions. Field Offices are listed under U.S. Government in your local phone book or visit our website(s): After Prescribed Fire se of driptorch start escribed fire. Yes, fire has many faces. It is a natural and vital element in our forests and grasslands. Through our wise use of fire we will realize a future where fire plays a necessary role in our wildlands’ cycle of life. Planned low-intensity fire has removed dangerous dead wood buildups • Forest retains its natural health • Threat of intense and harmful wildfire is gone • Forest Service - www.fs.fed.us/r6 • Bureau of Land Management www.or.blm.gov Native plants return quickly after fire.