Focusing Close to Home: Building Volunteer Efforts in a Small Town

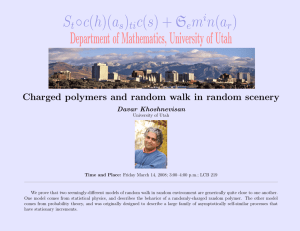

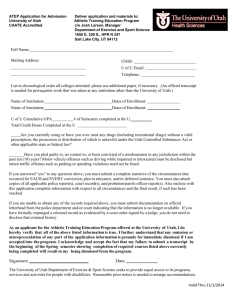

advertisement

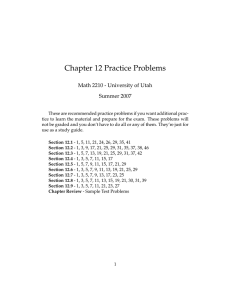

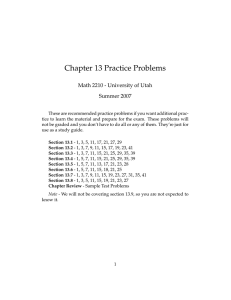

Focusing Close to Home: Building Volunteer Efforts in a Small Town Linda Seibert Abstract—Natural resource managers in the West often work out of small towns. The areas they manage are vast, and human resources are scarce. While the American Bird Association and other national organizations are excellent at recruiting volunteers to help with bird monitoring and research projects, enticing volunteers to small towns and remote areas can be a frustrating experience. While agencies should continue to recruit volunteers through national groups, they also should encourage homegrown efforts. Local people may actually be the most productive volunteers. Bird clubs are obvious sources for candidates, but commercial outfitters such as river guides and outdoor schools should not be overlooked. Natural resource managers in the western United States often work out of small isolated towns. The areas they manage can be vast, and human resources are usually scarce. An example is the town of Moab, Utah, which includes offices of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), National Park Service (NPS), and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), but only 5,000 people. Utah’s only urban area is 200 miles away. Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) coverage is light in such a remote area, and other types of avian distribution data also are spotty. While the effective use of volunteers can help to fill the void for surveys and management of birds and their habitat, finding volunteers in remote areas can be a frustrating experience. Wildlife biologists in the Moab District were interested in developing a volunteer program for bird work. We initially believed that we could not locate sufficient volunteers within our own small towns, so we tried to develop a program focused around national recruiting with the American Birding Association (ABA) and several local outdoor education schools. We had only limited success with these efforts, however. Then we began to realize that we had been ignoring many talented volunteers right in our local area. National and Regional Recruiting Efforts _________________________ Bureau of Land Mangement offices in Utah have tried to tie in with national and regional recruiting efforts. For example, many of us have advertised projects with the ABA. The Moab District also has worked with two outdoor education schools In: Bonney, Rick; Pashley, David N.; Cooper, Robert J.; Niles, Larry, eds. 2000. Strategies for bird conservation: The Partners in Flight planning process; Proceedings of the 3rd Partners in Flight Workshop; 1995 October 1-5; Cape May, NJ. Proceedings RMRS-P-16. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Linda Seibert, Bureau of Land Management, 82 East Dogwood, Suite M, Moab, UT 84532. 244 in our area—Canyonlands Field Institute (CFI) and Four Corners School of Outdoor Education (Four Corners)—to advertise bird watching trips that would focus on bird inventories. Southeast Utah is a tourism hot spot, and ecotourism is extremely popular, so asking people to come bird watching in combination with a river or backpack trip seemed like a natural sell. Disappointingly it wasn’t, with a few exceptions. For example, every year Four Corners offers a wildliferelated trip, generally tied to a desirable river, for which they recruit an expert guide and advertise nationally. Their most successful offering, a trip called “In Pursuit of the Peregrine,” has gathered useful data on Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus), with many new eyries documented in remote areas in southeastern Utah. These sightings have added to Utah’s statewide database and have allowed us to support the present proposal for delisting the species. However, during some years this trip has not drawn enough interest to be conducted. During one year BLM and Four Corners worked together to offer a “Neotropical migrant” inventory on the San Juan River. Only one person signed up. A similar trip was advertised with CFI, and also was unsuccessful. As another example, Utah BLM’s Richfield District advertised through ABA for someone to conduct point counts in riparian areas that are subject to special management. They found two excellent birders, both Utah residents. One of them, a college professor, used the opportunity to take his family on weekend camping trips. Meanwhile our district attempted to advertise through ABA several times with no response. Our failure may well have been caused by poor marketing or poorly thought out projects. Local Successes ________________ Initially we were disappointed with our inability, or only limited success, in recruiting volunteers. Then we began to realize that a great deal of useful birding was going on in our immediate area, and almost no recruiting had been needed to accomplish it. For example, although our town has no chapter of the National Audubon Society (NAS), a nucleus of enthusiastic birders do come together for Christmas Bird Counts (CBCs). Another focal point for bird enthusiasts is Canyonlands Raptor Center, a rehabilitation program run by a married couple named John and Marilyn Bicking. Their efforts, along with other local birders, proved to be far more significant than those that we purposely had tried to recruit. The Bickings moved to Moab from New Jersey in 1984. There Marilyn had worked in a rehabilitation center, and she felt a need for one in southeast Utah. In the past 11 years, they have cared for 1,450 hundred raptors, including 125 eagles. In addition, they are very involved in raptor habitat USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-16. 2000 management issues. They have taken an interest in the known Utah Bald Eagle population, consisting of three active nests in the southeast part of the state. They have promoted and assisted with banding and genetic studies, and participated in the development of interagency management plans. Two of the nests are along popular rafting areas, where several years ago my agency proposed to build a new boat ramp in a location close to one of the nests. The Bickings were concerned about the location, and were instrumental in getting it changed when they rallied commercial and private boaters to petition BLM to find a different location. The Bickings also have used their own funds to hire a man named Nelson Boschen to monitor eagle nests and to search for new ones. A self-taught naturalist, Nelson puts in many more hours than those for which he is paid, as he ensures that bald eagle chicks successfully fledge. He also has added greatly to our knowledge base by making detailed observations of eagle foraging and feeding activities, by conducting a BBS on the Colorado River, and by organizing the CBC for the Moab area. As another example, Gail Lea, a school librarian, devotes her summers to birding. She also has added greatly to bird distribution data in southeastern Utah. She monitors several peregrine eyries in the Moab area; assists the NPS by conducting several BBSs and by monitoring raptor nests; she has helped BLM with avian inventories on public land; and she now organizes the CBC. Reaching and Organizing the Right People ________________________ Even a small town can produce an abundance of volunteers and volunteer projects. The first problem is finding the USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-16. 2000 people; the second is using them effectively, focusing their energy on the most important needs. Several things should be kept in mind. First, have your strategies in place. In Utah we have had interagency work groups for priority species such as Peregrine Falcon, Mexican Spotted Owl, and Bald Eagle. We hold regular meetings with discussions on research, inventory and monitoring, and management issues. Non-agency biologists and non-professionals always are invited to these meetings. They are excited to be part of the process, and are more likely to offer their help. This is how the Bickings became involved financially with our bald eagle monitoring, and how Gail Lea took responsibility for monitoring peregrine eyries. Of course, the same tactics should be used with state Partners in Flight meetings. Then regional and state plans can be used to direct volunteers toward appropriate inventory, monitoring, and project needs. Second, seek out opportunities for ties with the ecotourism and environmental education communities. We are fortunate to have several schools in southeast Utah that specialize in ecotourism. Although such groups don’t exist everywhere, many possibilities exist with college classes taking field trips, tour companies who may want to diversify, and established groups such as Hawkwatch. Third, solicit input from local birders and other citizens when making management decisions that affect avian habitats. This process can make local people feel a sense of ownership that will encourage more participation in the long run. But be prepared to hear opinions that you may not welcome. You cannot use this tactic unless you are honestly going to listen, because people will be very disappointed if they feel their input was ignored, and trust will be lost. Finally, remember to work with national and regional groups such as ABA or NAS. They are well-established organizations with recruiting mechanisms in place. 245