The Influence of Anchor-Chaining on Watershed Health in a Juniper-Pinyon

advertisement

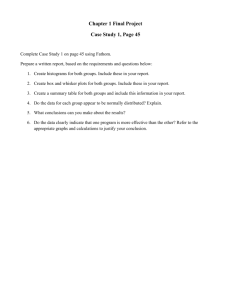

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. The Influence of Anchor-Chaining on Watershed Health in a Juniper-Pinyon Woodland in Central Utah M. E. Farmer K. T. Harper J. N. Davis Abstract-In 1990 the U.S. Forest Service anchor chained and seeded 121 ha ofjuniper-pinyon woodland in Spanish Fork Canyon. Twenty, 10 m 2 runoff-plots were established in 1991, to quantify anchor chaining's effect on runoff and soil erosion. Plots were paired, one in the chained area and one on comparable terrain and soil type in the untreated juniper-pinyon woodland. Each enclosed runoff-plot channels runoff water and suspended sediments into collection containers. During five years of data collection, unchained plots produced 5.8 times more runoff and 9.2 times more sediment than chained plots. Ground cover values for runoff plots show that vegetation increased from 27.1 percent in 1991 to 41.3 percent in 1995 on chained plots, while litter increased from 22.6 percent to 51.5 percent during the same time period. Vegetation cover on untreated plots varied from 7.5 percent in 1991 to 3.4 percent in 1995. Litter cover averaged 18 percent. Results indicate that anchor chaining significantly reduced runoff and soil erosion by providing more protective ground cover. Juniper-pinyon woodlands are an important rangeland type in the western United States where it currently covers about 24.3 million hectares. In Utah, Juniper-pinyon woodlands cover approximately 6 million hectares. These woodlands have greatly expanded their distribution in the past 150 years because of effective .fire control and heavy grazing by domestic livestock (West 1984). Without competition from a vigorous understory of grasses, forbs and shrubs and occasional wild fires, pinyon-juniper woodlands have become more dense and claimed much of the available nutrient and water resource previously used by a heavier cover of understory plants (Doughty 1986). Areas dominated by pinyon -j uni per prod uce little useable forage for wildlife or domestic grazers, and the bare inters paces are prone to erode during high intensity summer storms. Juniper and pinyon trees can often survive for 600 to 1000 years. Without some sort of mechanical removal, they may dominate a site for years and put at risk soils that support the ecosystem (West 1984). In: Monsen, Stephen B.; Stevens, Richard, comps. 1999. Proceedings: ecology and management of pinyon-juniper communities within the Interior West; 1997 September 15-18; Provo, UT. Proc. RMRS-P-9. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. M. E. Farmer is a Range Science Specialist, Utah Department of Agriculture, 735 N 500 E, Provo, UT 84606. K. T. Harper is a Professor in the Departmen t of Botany and Range Science, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602. J. N. Davis is a Research Biologist, Utah Department of Wildlife Resources, 735 N 500 E, Provo, UT 84606. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-9. 1999 Anchor chaining is a tree removal technique that has been used for the past 50 years. It is an economic method of converting juniper-pinyon woodland to vegetation rich in herbaceous perennial plants similar to that existing at the time of settlement of the region by European peoples. Many land managers have long assumed that reducing tree cover and encouraging grass, forb and shrub cover had a positive effect on infiltration, runoff and soil erosion on watersheds heavily dominated by juniper and pinyon, but quantitative data to support that assumption are uncommon. The purpose ofthis study is to quantitatively document the influence of anchor chaining on watershed health in juniper-pinyon woodland. Methods To determine the effects of chaining on runoff and soil erosion, 10 paired, 10 m 2 runoff-plots were placed, one in the chaining and one in a comparable unchained area. The enclosed plots channel runoff water and suspended sediments down slope into a pipe connecting a series of covered containers. A storage rain gauge was also placed near each plot to estimate precipitation on the plot. Runoff water was collected periodically and its volume recorded. Sediments were collected, weighed, oven dried and re-weighed. Water content in sediment samples was added to the runoff total. Ground cover values were estimated using a modified Daubenmire (1959) cover estimation procedure. Percent cover of vascular plants, bare ground, rock, litter and cryptogamic plants was estimated annually at each runoff-plot. Results --------------------------------------All runoff plots were placed during the summer of 1991. Data were collected from August through October of that year. During that period, untreated control plots produced an average of nearly 6 times more runoff and 9 times more sediment than chained plots. In 1992 data were recorded from May through October. Control plots, during that six month period, generated an average of 5 1/2 times more runoff and over 6 times more sediment than the chained plots (fig. 1 and 2). During the summer (May-October) of 1993, control plots produced 3 times more runoff and over 6 times more sediment. In the first summer after chaining, chained plots averaged 27.1 percent vegetative cover, compared to 6.2 percent on untreated plots (table 1). Protective ground cover consisting of vegetation and litter, averaged 49.7 percent on chained 299 80 70 Il k/ 60 Table 1-Relative percent ground cover of control and chained runoff plots. Each year's total is an average of 10 measurements. ~ v': ;4 [/i 50 ~ ... ~40 :::J 30 Legend ~ I - control lSI /'! chained : 1,J// 1 20 . ~ I (/~ 10 1...,.;1 ~ Q .115.7 ~ ~ ~ I- ~, ./~~ I 1991 1992 •• / 1995 1993 Figure 1-Average liters of summer runoff from 1991 to 1995. Each year's total is an average of 10 measurements. plots and 20.9 percent on control plots. In 1992, vegetative cover averaged 43.3 percent on chained plots and 7.3 on control plots. Protective ground cover averaged 70.2 percent on chained plots while control plots averaged 28.3 percent. By 1995 vegetative cover on chained plots averaged 41.3 percent and protective cover (vegetation and litter) averaged 92.8 percent. Untreated control plots averaged only 3.4 percent vegetation cover and 18.2 percent protective cover. Discussions __________ The primary forces which are related to water erosion are, raindrop energy and surface runoff, which remove and transport soil particles (Blackburn and others 1986). Vegetation is important in impeding overland flow and reducing Unchained plots 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 Average Bare ground Rock Litter Vegetation 46.6 31.1 14.7 7.5 31.6 40.1 21.0 7.3 39.3 33.5 19.6 7.6 50.6 25.1 19.4 4.8 43.8 33.5 14.8 3.4 42.4 32.7 17.9 6.1 Chained plots Bare ground Rock Litter Vegetation 43.1 7.2 22.6 27.1 25.1 4.7 26.9 43.3 19.5 6.9 37.9 35.6 27.1 3.8 38.1 31.0 15.4 13.7 51.5 41.3 26.0 7.3 35.4 35.7 raindrop energy. Blackburn and others (1986) state that the amount of vegetative cover is the primary erosion controlling factor. Control areas on the Spanish Fork Site during the study period, contained an average of6.1 percent vegetation cover, 60 percent of which was tree canopy cover. Simanton and others (1991) discovered that the significance of canopy cover was small compared to ground cover in soil erosion prediction models. Khan and others (1988) found that as canopy height increases the soil erosion rate also increases. Ground cover of understory vegetation is most effective at reducing soil erosion. Anchor chained sites in the Spanish Fork study provided more uniform protective vegetation cover closer to the ground surface than untreated juniper-pinyon sites. Conclusions __________ Over the five year period of study, Anchor Chaining allowed vegetative cover to increase 6 times on the average plot and litter cover to increase an average of 2 times. Runoff, on the chained plots, was reduced an average of 6 fold and erosion reduced an average of9 fold. Results show that anchor chaining significantly reduced runoff and erosion by providing more protective ground cover. //// 800 35~--------------------------===========----- - ~/ ./' 700 ~ ~ 304--------------------------- ./'~/ 25~-------------------------- 600 J//I 500 400 - 300 200 100 ~20J--------------------------- o Legend ~ control ~ chained u 104---------------------------V j.,/ J// V J/ V/ ---'?? a / c:s:.::: 1991 Jl08 ~ ~ 1992 1993 ~ .~~ 1994 Figure 2-Average grams of sediment yield from 10 plots during the summers of 1991-1995. 300 <fl. 15 ,.--- .. ~ 1995 / Chained Unchained / • Grass fZI Forb • Shrub ~ Tree Figure 3-Average relative percent vegetation cover by class of unchained and chained runoff plots from 1991-94. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-9. 1999 Acknowledgments This work was facilitated in active cooperation with the Brigham Young University, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, USDA Forest Service, Uinta National Forest, and the Intermountain Research Station, Shrubland Biology and Restoration Research Work Unit. Research was partially funded by Pittman Robertson Agreements W-82-Rand W-135- R. References ---------------------------------Blackburn, W. H., T. L. Thurow and C. A. Taylor, Jr. 1986. Soil erosion on rangelands. In: Proceedings, Range Monitoring Symposium, Society of Range Manage. Denver, CO: 31-39. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-9. 1999 Daubenmire, R. 1959. A canopy coverage method of vegetational analysis. Northwest Sci. 33: 43-66. Doughty, J. W. 1987. The problems with custodial management of pinyon juniper woodlands. In: Proceedings, Pinyon-juniper Conference, USFS Gen. Tech. Report INT-215: 29-33. Khan, M. J., E. J. Monke, and G. R. Foster. 1988. Mulch cover and canopy effect on soil loss. Trans. of the Amer. Soc. Agr. Engr. 31: 706-711. Simanton, J. R., M. A. Weltz, and H. D. Larsen. 1991. Rangeland experiments to parameterize the water erosion prediction project model: vegetation canopy cover effects. J. Range Manage. 44(3): 276-282. West, N. E. 1984. Successional patterns and productivity potentials ofpinyon-juniper ecosystems. In: Developing Strategies for Rangeland Management. Westview Press, Boulder: 1301-1332. 301