Document 11871807

advertisement

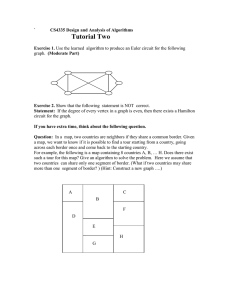

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Planning for ''Natural'' Disaster: Unsustainable Development of the U.S./Mexico Border Helen lngram 1 Abstract.-Planning is designed to insure that undesirable outcomes do not occur and that decisions are based on knowledge and reason. However, past planning on the border has been insensitive to the environment and sustainability. Planning for agricultural development has been narrowly focused on hydrology and engineering without consideration of impacts on the natural world. Industrial planning has focused on jobs and economic growth, again without real consideration to impacts on natural systems. The consequences have been environmental degradation and threats to human health. More recently NAFTA has promised to avoid these earlier planning limitations by expanding economic activities, correcting environmental problems and focusing on sustainability. It remains to be seen whether the promises made by NAFTA and other planning efforts can be kept. There are real limits to the water available for growth and development along the border. To ignore these limits is to guarantee disaster. INTRODUCTION Similar to recent years, the winter of 1997-98 in Southern California was marred by natural disasters. While the earthquakes and fires sometimes threatening human and wildlife and property did not erupt, the winter rainstorms and high seas of El Nino flooded houses, swept away beaches and the parks, playgrounds, and dwellings. High winds felled large eucalyptus trees often upon parked cars and buildings. Once the hillsides in lovely communities like Laguna Beach were thoroughly soaked, the mud slides began, and some uphill residents were horrified to witness the creeping of their front lawn through their downhill neighbors kitchen door. While treated by the media as a freak of nature-national television audiences repeatedly were entertained with scenes of gigantic waves crashing through windows of luxury apartments at Huntington Beachthe reality is that almost every surprise was entirely predictable. As William Cronon observed in his fine essay "In Search of Nature" labeling a 1 Warmington Endowed Chair, School of Social Ecology, University of California at Irvine USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-5. 1998 3 disaster "natural" implies there is nothing we can do about it. It is just the way things are, and we'd better resign ourselves to the nasty temper of much maligned Mother Nature. Yet, the worst effects of El Nifio were visited on the developments expensively planned with beautiful architecture and landscaping that ignored key features of topography and climate. Beaches are in a constant flux of washing away and rebuilding, often in different locations. The unstable soils of the low hills once held loosely in place by native grasses that thrived on winter rains shift easily under the heavy weight of human dwellings and highways. Most trees in Orange County are exotic, including the fast growing eucalyptus that quickly provides shade and the illusion of solidity, yet shatters when subjected to coastal winds. 2 Transforming terrain has long been a thriving way of life in the greater American Southwest where since the beginning of the twentieth century applied hydrology and agricultural engineering have diverted the waters of the Colorado River first to make cotton and citrus, and now to make condos cover the deserts of California and Arizona. The accomplishment of such alterations have taken place under the guise of rational planning and created an illusion of human capacity to impose not only order upon the environment but also to alter the environment to conform to human will. For the most part, large investments of energy and capital so far have allowed humans mainly to ignore whatever limits may ultimately be imposed by landform and climate. This is not to be the case, however, in regard to one area, the U.S./Mexico Border, and one resource, water. The argument of this paper is that the growing reliance upon water supplies that simply are not dependably available, even in the relatively near term, is to invite disaster. Ironically, "rational" planning, purposeful policy, and infrastructure development have set the course toward practically certain human and ecological crisis. GROWTH OF POPULATION ON THE U.S./MEXICO BORDER The U.S./Mexico border region was home to more than ten million people in 1995, an increase of two million in only five years. Ninety percent of the border population lives in urban areas, and there are 14 major sister city pairs along the border stretching from San Diego-Tijuana to Brownsville/Matamoras. Table 1 provides population growth figures of border states. William Cronan, "In Search of Nature:" in Cronan ed. Uncommon Ground: Toward Reinventing Nature, New York: W. W. Norton and Co, 1995. 2 4 USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-5. 1998 Table 1. Population Growth on the U.S./Mexico Border %Change 1980 Area NA Binational Border States NA U.S. States Mexican States NA 5,149,510 Sister Cities 2,662,810 U.S. Cities Mexican Cities 2,486,700 1990 8,301,000 4,412,000 3,889,000 6,902,590 3,478,490 3,424,100 %Change 1980-90 NA NA NA 25% 23% 27% %Change 1990-95 1990-95 1980-95 10,305,000 24% NA 5,230,000 16% NA 5,075,000 23% NA 8,051,140 14% 56% 3,868,540 10% 31% 4,182,600 18% 41% Source: EPA, U.S.-Mexico Border XXI Program Framework Document As the table indicates, the percentages of population increase in this area is astonishing and growth is even more rapid in Mexico than in the United States. Further there is no indication of growth abatement in recent years since the rate between 1990 and 1995 surpasses that of the previous ten years. Concentration of population in cities and the attendant problems of urbanization have drawn the most attention, but territorially, most of the border remains rural. The rural economy of much of the border is based upon agriculture which is highly dependent upon irrigation and relatively sophisticated technology. The Imperial and Mexicali Valleys have historically been big producers of cotton, alfalfa, wheat and sorghum. 3 The lower Rio Grande Valley in the United States is a source of pecans on the U.S. side and of alfalfa on the Mexican side. Cattle ranching has been particularly important in the state of Sonora and in recent years the introduction of bufflegrass and the diversion of water to irrigate this exotic fodder has introduced increased water demand for ranching. 4 In the spaces between cities and the farms there are ecosystems that support more than 450 rare or endemic species. In addition there are 85 threatened or endangered species of plants and animals. More than 700 neotropical migratory species, including birds, mammals and insects use the borderland habitats during their annual migrations. A majority of species in the border area are dependent upon riparian habitats. Within the U.S. there are eight national wildlife refuges within twenty-five miles of the border. In addition there are several national parks and monuments in the United States on or near the border, including Big Bend National Park, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, and protected areas in Mexico including El Pinacate, Canon Santa Elena and Maderas de Carmen adjacent to Big Bend, and Laguna Madre de Tamaulipas. 3 Francisco Alba, "Mexico's Northern Border: A Framework of Reference" in Natural Resources Journal, October, 1992, Volume 22, No.4, October, 1982. 4 Luis Vila, "Acaparan ganaderos el agua en Guaymas: miles of campesinos, en las miseria par la Sequia, El Financiero," May, 14, 1998, p. 16. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-5. 1998 5 INCIPIENT WATER WARS The most salient features of the U.S./Mexico region is aridity. Along most of the border, rainfall is eight inches a year or less. What surface water is available evaporates quickly under the stress of very high summer temperatures. Surface water resources in the border include two major river drainages, the Colorado River and the Rio Grande, both of which flow north to south, and a number of other streams, sometimes intermittent, many of which flow south to north. . In addition to low rainfall, a second notable feature of the desert border region is enormous variability in water supply, with dramatic swings in rainfall and runoff. In prehistory, climatic variability was closely associated with viability of human settlement. Long-term tree ring data in the Rio Grande Basin, for instance, show a pattern in which below average rainfalls have occurred for as long as 200 years at a stretch. The flowering of Native American cultures in the Rio Grande Basin from 200 BC to the nineteenth century took place only during those peak periods of a century or more when rainfall consistently exceeded the long term mean. Further, there are very large year to year and seasonal variations in streamflows on the Rio Grande. 5 There is no reason to believe that the droughts of 1993-96 which were so enormously harmful to Mexican agriculture and precipitated both international conflicts between the states of Texas and Chihuahua and between urban and rural areas in Mexico are unlikely to occur again. The long-term historical record confirms similar variability on the Colorado River. Tree-ring reconstructions suggest that over the last 500 years, the lowest 80 year mean at Lee's Ferry is less than 11 million acre feet which corresponds to a 27% decrease in natural flow compared to the 1906-83 stream gauge record. 6 A third significant feature of water on the border is the critical importance of groundwater supplies. Uncertain surface water sources are complemented by numerous groundwater basins which feed important wetlands areas that support biodiversity and the region's natural system. In the first part of the nineteenth century the major river systems also were totally allocated and quantification of water rights on minor streams since then have fully apportioned their waters also. As a consequence, more recent users have often turned to groundwater as an alternative source. Prior to 1940, groundwater basins in any areas along the border were in hydrologic equilibrium, that is, water inflow was approximately equal to 5 John Hernandez, "Long term climatic and streamflow Records on the Rio Grande" paper presented to bi-national conference, "Coping with Scarcity in the Rio Grande/Rio Grande Drainage Basin: Lessons to be Learned From the Droughts of 1993-1996" Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico, October, 1997. 6 Linda Nash and Peter Gleick, "The Colorado River Basin and Climate Change: The Sensitivity of Streamflow and Water Supply to Variations in Temperature and Precipitation," Pacific Institute for Studies in Development, Environment and Security, December, 1993. 6 USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-5. 1998 outflow, based on long-term flow conditions. 7 Since then water withdrawal and use has far exceeded recharge and degraded water quality resulting in significant effects upon the resource. There are areas on the border where aquifers have reached critical levels. It is estimated, for example, that the Hueco Bolson, upon which both the cities of El Paso and Juarez depend, has no more than twenty more years of usable supply. Groundwater overdraft each year is nearly two million acre feet in Southern California and the Mexicali Valley. 8 Such overdraft is far from sustainable. Because of its dependence on only two major water systems with huge drainage basins, the border is acutely at risk from human induced climate change. Looking only at the Colorado River, one widely cited study of general scenarios based on general circulation models of climate suggests that certain aspects of the hydrology and water supply system of the river are extremely sensitive to climate change that could occur over the next several decades. Not only are significant changes of runoff possible, but the ability of existing water supply systems to mitigate the worst effects are limited. Reservoir storage lessens impacts for only a short period of time. An increase in temperature of only 2 degrees, with no change in precipitation would cause mean annual runoff in the Colorado Basin to decline by 4 to 12 percent. Further, under conditions of long-term flow reduction salinity increases dramatically. 9 Such a completely plausible change would dramatically affect water reservoir storage, water deliveries and water quality on the lower Colorado River shared with Mexico and would likely precipitate international tension, not to mention human crises. Even without considering such a troubling future, there is sufficient current water conflict to signal future problems. Cities are having to look outside their adjacent areas and river basins to find new supplies, and rural farmers are seeing an essential ingredient to their livelihood drained off to quench the thirst of cities. Shared aquifers are being depleted with both nations realizing that what supplies they do not capture will be sucked up and used on the other side. The winners and losers in the struggle vary over time and from place to place, but consistently the natural world of flora and fauna is bearing the brunt of shortages. Riparian areas are disappearing, and with them the loss of many species dependent upon wet habitat. Streams, once flowing much of the year, have dried up with insufficient water to feed the trees and shrubs which once traced them like lifelines through the desert. The largest natural springs in the 7 Anderson and others, "Geohydrology and Water Resources of Alluvial Basins in South-Central Arizona and Parts of Adjoining States:" U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1406-B, 1972. 8 Jason Morrison, Sandra Pastel, Peter Gleick, Sustainable Use of Water in the Colorado Basin, San Francisco: The Pacific Institute, November, 1996. 9 Nash and Gleick. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-5. 1998 7 border region, Quitobaquito, within the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, and the endangered desert pupfish found there is at risk. Nearly all the Mexican land adjacent to the Monument is undergoing intensive agricultural development and urbanization. Groundwater pumping from the Sonoyta river basin has resulted in dropping the water table sufficiently to threaten the spring. In addition, biocide drift from aerial spraying of crops are threatening rare plants and insects. 10 Further, the water quality upon which natural species depend has become degraded. For example, high levels of pesticides and increased concentrations of salts and selenium in the Salton Sea are resulting in deaths of ducks and other bird species and the malformation of offspring. PLANS PAVE THE WAY FOR PROBLEMS The present water conflict is the direct result of rational, discipline based planning based on narrowly focused goals and instrumental reasoning. Goals changed over time, but in each case water was treated as a property, product or commodity, not an integral part of the natural system in a desert where scarcity is the rule and strategies to limit water use and survive periodic droughts are essential. Making the Deserts Bloom Shortly after the turn of the twentieth century both the U.S. and Mexican governments turned their attention to irrigation in deserts with rich soils and long growing seasons. So called reclamation policies accepted legal definitions of water as property of individuals and nations. Large scale engineering works moved water like a raw material through production processes. Prevailing water law and politics ruled that not to use water was to lose it. There was a fierce competition among the two nations and among subnational regions to put water to work through dams, diversions, reservoirs and irrigation projects as rapidly as possible so as to lay claim to it. A 1944 treaty on Colorado and Rio Grande waters divided them like slicing loaves of bread, ignoring the systemic characteristics of water and the many unintended consequences associated with storage and diversion. But once rights were secure, government planners moved quickly to divert water from its natural course to create agricultural wealth. The development of the Imperial Valley was the largest of many such projects. With less than three inches of rainfall per year and summer temperatures ranging to 120 degrees, the area would seem unsuitable for intensive development were it not for bureaucratic and engineering ingeU.S. Department of Interior, National Park Service, Organ Pipe Cactus Statement for Management, September, 1994. 10 8 USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-5. 1998 nuity combined with constituency pressure and Congressional log rolling.11 While the early diversion of Colorado River water into the valley was private and involved as many as 160,00 acres by 1909, the enterprise might well have gone the way of gold rush miners had it not been for the help of federal reclamation planners and engineers. Beginning with federal emergency rescue help when the project's headgate in Mexico failed resulting in the diversion of the whole river into the Valley, the enterprise was beset by troubles that only large federal subsidies and engineering expertise could resolve. The Bureau of Reclamation accommodated the needs of the Valley through the erection of a series of dams, diversions and canals. Originally intended for small farmers, the 160 acre limita.tion built into reclamation law was never observed in practice, and later was all but abandoned. For more than a quarter of a century the Imperial Valley has provided bountiful harvest of fodder, food and fiber and not a few great individual and corporate fortunes. Today, like other water users on the border, the Imperial Valley is feeling the pressures of over exploitation. One source of pressure comes from environment. The so called Bono Bill, passed after the death of Congressman Sonny Bono, mandates that the salinity levels in the Salton Sea not be allowed to increase. Since agriculture is the major contributor to salinity increase, it may well have to foot the bill for preventive measures. Another source of pressure comes from urban competition for water resources. The City of San Diego, the last in line for the over appropriated Colorado River, has been pressuring the Imperial Valley to sell irrigation water to the City, agreeing to pay for lining canals and other conservation measures which could keep agriculturalists in business while using less water. Unfortunately, the lining of the All American Canal will put a stop to fugitive flows to groundwater sources upon which farmers in the Mexicali Valley depend. The Mexicali Valley is an irrigated agricultural development in Mexico of approximately the same size but of lesser productivity than the Imperial Valley. It is reasonable to expect the Mexicans to react strongly to the loss of this long established water source even if it is outside the treaty obligations. Border Industrialization Just as the spread of agriculture in arid borderlands was the result of purposeful governmental planning and policy, so, too, has been urban development. While the U.S. Government has fueled urban growth through the location of military installations, and funding of water and highway projects throughout the West, the main impetus for urban development on the border has come from the Mexican government. The Border Industrialization Program was the brainchild of economic planners 11 Phillip Fradkin, A River No More, Knopf, New York, 1984. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-5. 1998 9 :'• .. :·, and experts in international trade. Designed to generate jobs in Mexico Border Cities through the establishment of assembly plants, or maquiladoras, the program initially enjoyed a modest success. Beginning in 1983, stimulated by simplified regulations and lower water costs in dollar terms brought by devalued Mexican currency, the industry saw increases that averaged 14.4% a year in numbers of workers and nearly 11% of numbers of new plants each year for the next ten years. In 1993, there were 2, 170 plants employing 540,930 workers. 12 The economic importance of the Maquila program to Mexico can not be overemphasized. This sector of the economy continued to grow even during the latest economic downturn. As well as providing a source of employment for· Mexico's huge population just entering the workforce, the program is a source of hard currency badly needed in repaying the Mexican debt. The principle driving force for bringing maquilas to the border has been the low cost of Mexican labor, roughly one-eighth of that in the U.S. However, the low costs of plant sites is also important. Maquilas have paid little or nothing for the additional infrastructure burdens upon schools, highways, and water supplies caused by their operations and the workers they attract to the border. Further, up until the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement, the enforcement of environmental regulations was relatively lax. Just as reclamation plans and policies have had unintended and very negative side effects particularly adverse to water quantity and quality, border industrialization has resulted in additional serious problems. The population explosion of border cities quickly out paced infrastructure development, particularly that related to water supply and sewerage treatment. The colonies that burgeoned particularly on the Mexican side of the border usually had no dependable water service. In many cities almost a third of the residents in 1990 did not have uninterrupted, convenient water supplies. While water was piped to spigots in some neighborhoods, many residents depended on water trucked into houses several times a week where often it was stored in uncovered and unsanitary barrels. Sewerage was handled even more poorly than water. Broken sewer pipes in ancient water systems combined with leaky water supply pipes with low pressure contributed to the contamination of the water supply. Raw sewerage was spilled into streams and ran down roads and streams creating very serious health hazards. Since the direction of flow in a number of urban water courses is south to north, contaminated water flowed across the border to jeopardize U.S. as well as Mexican citizens. Public attention to the poor state of environmental protection was drawn to the border as a 12 Paul Ganster, "The U.S. Border Region" in Paul Ganster, Alan Sweedler, James Scott, Wolf Dieter-eberwein, Borders and Border Regions in Europe and North America, San Diego, San Diego State University Press, 1997, p. 243-44). 10 USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-5. 1998 result of the free trade agreement. National newspapers like the Christian Science Monitor and the New York Times ran series of stories labeling the U.S.-Mexico border an environmental war zone. 13 NAFTA Side Agreement Planning The border side agreements were the conditions added to NAFTA by the Clinton Administration to make the accord more acceptable to labor and environmentalists. While the agreements have had many beneficial effects for the border, including much larger funding for border projects directed to many federal and state agencies and the initiation of many new environmental programs, my main argument is that their failure to address sustainable water supply questions while encouraging the further expansion of water use on the border is a perpetuation of planning and policy that lead toward environmental disaster. The environmental side agreements included the creation of a pair of new institutions, the Border Environment Cooperation Commission or BECC and the North American Development Bank or NADBank. The purposes of these institutions is to review, certify and fund border infrastructure projects. While other institutions had previously existed with much of the same mandate including the International Boundary and Water Commission and the Border Environmental Plan put together by the Environmental Protection Agency and Mexican counterparts, the performance of these institutions was clearly inadequate for the new circumstances. In particular, the interests of states and people living on the border were poorly represented, and the funding of projects depended on uncertain national legislative appropriations processes. BECC in particular represents an improvement in openness and representativeness in that it has a bi-national board of directors with ten members, five from each country and decision making procedures to ensure that the views of states, local communities and members of the public are taken into account. NADBank has a bi-national board of six members, and is a good deal less open to public input. However, it is more open than most international development banks to public participation. Both institutions are jointly funded by the U.S. and Mexico. From the perspective of avoiding unsustainable development, however, the most important innovation of the environmental side agreements and the BECC was the adoption of different evaluation criteria for proposed projects. The BECC and the NADBank must, according to their rules, consider the need to conserve, protect, and enhance the environment and only sustainable projects are supposed to be certified. The economic criteria are also much improved over the politically driven past allocation of monies. Financing of projects is supposed to depend upon "user-pays" Helen Ingram, Nancy Laney, and David Guillilan, Divided Water: Bridging the U.S. Mexico Border, Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1995. 13 USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-5. 1998 11 principles through fees paid by the beneficiaries of the projects. Financing is supposed to come from public and private sectors. Another improvement of the side agreements is the commitment to community capacity building: Increasingly BECC has realized that an impediment to better water planning and management has been the lack of professional and technical capacity, particularly in smaller border communities. The institution has devoted staff resources and provided loans to secure the necessary technical support for communities to prepare project proposals. The level of such support, however, has by no means been adeq~ate. The real issue seems to me to be whether BECC and NADBank have been or promise to be effective in bringing level of industrial expansion and population growth more in line with sustainable levels of water use. If the answer to the question is not positive, then the side agreements will turn out to be no more than a rationalization or a half hearted attempt at planning that will lead to disaster. Following is an assessment of accomplishments and shortcomings. BECC and NADBank have gotten a slow start. Around 20 projects have been certified by BECC and less than a quarter of them have been financed by NADBank. Part of the problem has been staff instability and turn over. Within two years, there was a complete change in leadership at BECC. Another problem has been disagreement on the BECC board about its mission. Not all members have had the same level of commitment to openness and public participation and sustainability. Another problem has been the relationship of BECC to NADBank. It is not yet clear if NADBank can fund projects not certified by BECC and whether NADBank needs under the law to consider environmental as well as financial sustainability. 14 The commitment to sustainability may be more formal and symbolic than actual. No project has as yet been turned down on the grounds that it is environmentally unsustainable. This is the case even though many projects were planned and designed before the new regulations were put in place and reflect older, "engineering-fix" ideas about water management. Sustainable criteria has not led to projects that specifically encourage water conservation in ways other than water rate increases. BECC has a procedure in place whereby it certifies projects as simply sustainable or highly sustainable. However, there is no connection between this rating system and likelihood or priority of funding by NADBank. NADBank's position has been that BECC' s sustainability criteria are important, but for purposes of funding, bank directors are most interested in the ability of users to pay back loans, or financial sustainability. The argument is that the value of scarce water will be signalled to users through high water rates. While there is some logic to this argument, financial sustainability and environmental sustainability may in the long run be at odds. If the pay out of projects Mark f. Spalding and John J. Audley, Promising Potential for the U.S.-Mexico Border and for the Future: An Assessment of the BECC/NADBank Institutions," November, 1997. 14 12 II USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-5. 1998 depends upon projected population expansion and economic development, then infrastructure development becomes one of the forces driving growth. New industries and new workers need to be attracted to cities if projects are to be financially successful. Yet, this means increasing water demands pressing close upon very limited supplies. After all, the increase of population on the border has continued unabated since the passage of NAFfA. 15 Border infrastructure planning for sustainability begins to look like wishful thinking. PERSPECTIVES FOR THE FUTURE The whole purpose of planning is to avoid the tyranny of the accumulation of many small decisions which may be individually rational but collectively do not serve public welfare. Planning is supposed to guide societies to avoid undesirable outcomes and to reach scenarios which have been chosen on the basis of knowledge and reason. In the past, the planning done on the border has been insensitive to environment and to issues of sustainability. Plans guiding agricultural development were narrowly focused on hydrology and irrigation engineering, and failed to take into account many negative side effects, particularly to the natural world. Industrial planning initiated in Mexico, and implemented with the collaboration of the United States, suffered from similar myopia. Jobs, economic growth and hard currency materialized as planned but at a cost for which the border was unprepared. The consequence of rapid urbanization has been serious environmental degradation and threats to human health and natural systems. In contrast, environmental planning related to NAFTA embraced a more inclusive vision. Not only were economic opportunities to be expanded, but past environmental problems were to be corrected and future developments were to be guided by criteria of sustainability. Unfortunately plans may function to provide reassurance that things are on the right track when in fact they are moving in a dangerous direction. This paper has argued that unabated urban population growth in an arid region with limited and uncertain water supplies invites disaster. Human populations are particularly vulnerable because there are high proportions of poor, minority and underprivileged people who do not have theresources to take actions to protect themselves. Further, the area has significant ecological resources which will be terribly difficult to protect in trade offs with human health and welfare. Rich areas like Southern California may be able to afford to ignore, at least for the present, basic physical and climatic features of the area and recover from the "disasters" that are the inevitable consequences. The limitation of water resources, however, places a firm boundary on human development and population growth on the U.S./Mexico border going beyond which is to guarantee disaster. "Public Citizen, NAFTA's Broken Promises: The Border Betrayed." Washington: Public Citizen's Global Trade Watch, January, 1996. 15 USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-5. 1998 13