Document 11871743

This file was created by scanning the printed publication.

Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain.

Grazing Management In Arid Grasslands

Using Principles of Holistic Management

Kirk Gadzia

1

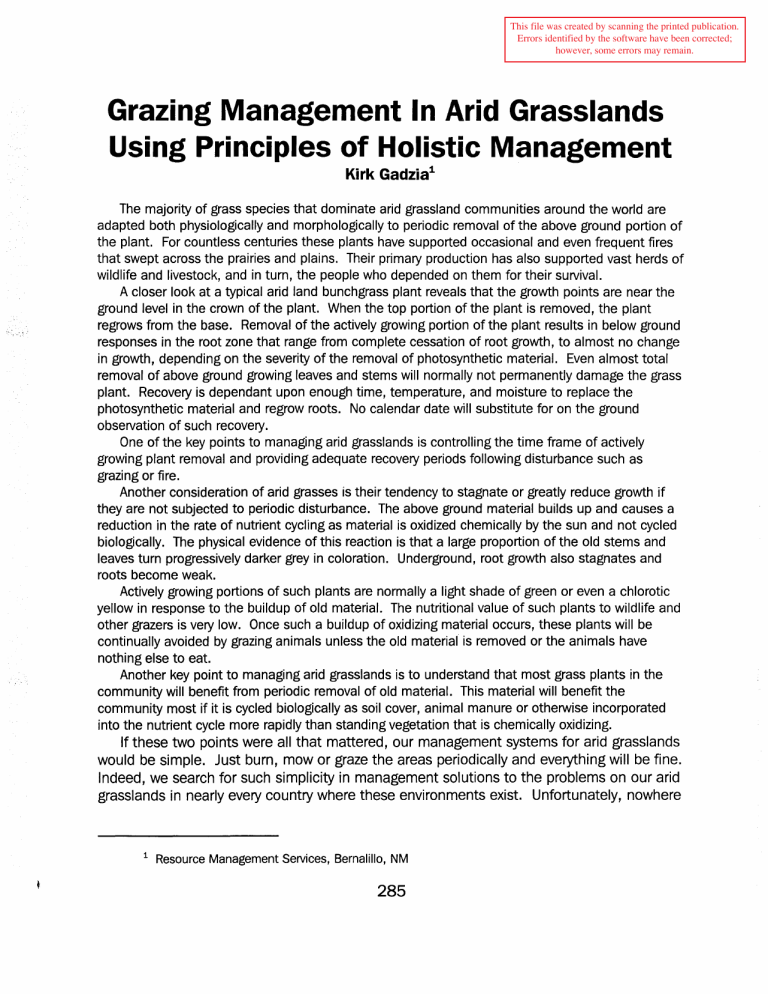

The majority of grass species that dominate arid grassland communities around the world are adapted both physiologically and morphologically to periodic removal of the above ground portion of the plant. For countless centuries these plants have supported occasional and even frequent fires that swept across the prairies and plains. Their primary production has also supported vast herds of wildlife and livestock, and in turn, the people who depended on them for their survival.

A closer look at a typical arid land bunchgrass plant reveals that the growth points are near the ground level in the crown of the plant. When the top portion of the plant is removed, the plant regrows from the base. Removal of the actively growing portion of the plant results in below ground responses in the root zone that range from complete cessation of root growth, to almost no change in growth, depending on the severity of the removal of photosynthetic material. Even almost total removal of above ground growing leaves and stems will normally not permanently damage the grass plant. Recovery is dependant upon enough time, temperature, and moisture to replace the photosynthetic material and regrow roots. No calendar date will substitute for on the ground observation of such recovery.

One of the key points to managing arid grasslands is controlling the time frame of actively growing plant removal and providing adequate recovery periods following disturbance such as grazing or fire.

Another consideration of arid grasses is their tendency to stagnate or greatly reduce growth if they are not subjected to periodic disturbance. The above ground material builds up and causes a reduction in the rate of nutrient cycling as material is oxidized chemically by the sun and not cycled biologically. The physical evidence of this reaction is that a large proportion of the old stems and leaves turn progressively darker grey in coloration. Underground, root growth also stagnates and roots become weak.

Actively growing portions of such plants are normally a light shade of green or even a chlorotic yellow in response to the buildup of old material. The nutritional value of such plants to wildlife and other grazers is very low. Once such a buildup of oxidizing material occurs, these plants will be continually avoided by grazing animals unless the old material is removed or the animals have nothing else to eat.

Another key point to managing arid grasslands is to understand that most grass plants in the community will benefit from periodic removal of old material. This material will benefit the community most if it is cycled biologically as soil cover, animal manure or otherwise incorporated into the nutrient cycle more rapidly than standing vegetation that is chemically oxidizing.

If these two points were all that mattered, our management systems for arid grasslands would be simple. Just burn, mow or graze the areas periodically and everything will be fine.

Indeed, we search for such simplicity in management solutions to the problems on our arid grasslands in nearly every country where these environments exist. Unfortunately, nowhere

1 Resource Management Services, Bernalillo, NM

285

are simple stocking rate reductions or burning prescriptions working to reverse the trend toward desertification on a global scale.

Community stability within arid grasslands depends not only on the health of the adult populations of plants and animals, but also the recruitment of young. Seeds of grasses that dominate arid grassland communities must therefore be able to germinate and establish for the communities to remain healthy. Seeds must be incorporated into soils and have seed to soil contact in a firm seedbed to successfully establish. While this concept is simple and well known to every farmer or gardener, it seems missing from our conception of arid grassland health. The crusting or sealing of soil surfaces in bare arid soils occurs in response to rainfall events. Such crusting inhibits the penetration of seeds and their subsequent establishment. The seeds of some species exhibit mechanisms to penetrate such crusting, yet many other species which are an essential component of a diverse and healthy community do not have such advantages.

While fire plays an important role in cycling nutrients, invigorating some species, and removing old vegetation in arid grasslands; it cannot break crusted soil surfaces. In fact, fire exposes large areas of soil surfaces to raindrop sealing action which tends to negatively affect the cycling of water. However, another role of fire is to attract grazing animals to the nutritious forage available in areas that have burned. These grazers in turn can break the soil crusts and provide necessary seed to soil contact for improved germination and establishment of new plants.

Periodic droughts and high rainfall years also played a role in the vast wheel of life rolling on the arid grasslands. Years of above average precipitation produced an excess of plant material, and afterwards a buildup in the game populations. Fuel buildups in turn encouraged fire that were eventually followed by drought years. High utilization levels occurred as forage resources became inadequate to support the game populations.

Locusts, and other major influences also played their roles. In short, such a dynamic population and production situation could hardly be described as static.

It is clear from considering this large view that it is not enough to weigh only the needs of the grass plant as a component of the arid grassland environment. We must consider the community as a whole. Such consideration will involve the interacting roles of plants, animals, soils, people and the changing rules and regulations we create to manage these interactions. Management of such complexity must be responsive to the needs of this overall community.

When we shift our view from managing arid grasslands to the larger whole of recreation, agriculture, forestry, fisheries and other interactions between humans and their environment we see few success stories in sustainability. Where we do see successful management, in nearly every case it is because the principles used to manage are based on natural laws or the simulation of natural processes. Such sustainable management systems rely on building biodiversity to retain stability. In addition, people are viewed as an essential component of the process, and not considered .. foreign .. to the ecosystem.

The natural principles that governed arid grassland development, biodiversity, and stability in nearly all areas of the world have been periodic disturbance by grazing animals, drought, floods, and fire. Migrating herds and their predators including humans responded

286

to regional climatic variations and natural and human induced fires to create an incredibly complex whole. Such community development is not easily duplicated by management prescriptions of stocking rates, season of use, fire management regimes, and other regulations governing the current management of many arid grasslands.

In Jordan, ancient Byzantine mosaics and hunting lodges in the desert attest to the once abundant wildlife of the area in times past. The arid oak savannah grassland and nomadic people that lived in these areas with their livestock are also depicted. Today these areas are treeless except for the monocultures of pine planted by the government and protected by armed guards. Perennial grasses still exist, hanging on in the shelter of rocky cracks, but are largely absent from the community. The majority of the surrounding countryside is being nibbled to death by settled nomads and their small resident herds of sheep and goats. Yet, where large herds and planned seasonal recovery has been used, rapid improvement has been documented.

While far from perfect, the nomadic livestock grazing that existed and sustained populations for many centuries in these areas was an approximation of natural grazing patterns by wildlife. Populations of both humans and livestock grew and starved in response to prevailing weather. In the last instant of time we have settled nomads in foreign countries, built fences, firebreaks and other developments in our own countries~ arid grasslands, and done our best to impose a static management regime upon a completely dynamic situation.

The change from relative productivity and stability towards instability and lowered productivity of arid grasslands in this country is well documented in some areas. In the desert southwest a shift from grassland to shrub dominated communities is often considered irreversible without major human and technological intervention. The long term rest or non-disturbance that is often recommended in such areas has produced few positive changes in overall ecosystem functioning. Without the vital component of large animals interacting within the system, rest alone seems insufficient to create much change.

There is no single simple prescription to manage arid grasslands and their myriad of values and functions. The changes wrought by human population buildup in our arid grasslands preclude the ~~return to naturell approach favored by some. This is because the human infrastructure of pipelines, roads, towns, etc .. , will not disappear even if livestock grazing is halted. Management models such as holistic management that recognize and attempt to mimic the pulses of energy that were an integral part of these environments show great potential. The concept of using life to make more life is a simple way of expressing this interaction. Arid grasslands did not develop as plant communities. They developed as communities of soil organisms, plants, herbivores, predators and human intervention.

Improvement of grazed arid grasslands in terms of biodiversity, soil cover, and other monitoring criteria is documented in many areas of this country and others around the world. There is abundant evidence that livestock can be utilized as a major component in the improvement process. Their role in providing periodic disturbance to soil surfaces, removal and cycling of plant materials must be emphasized and concentrated to be effective. These impacts must be incorporated with adequate time periods for soils, plants,

287

and animals to recover and utilize the energy provided by large animal in the system. If time and impacts are not controlled, the results will be negative as evidenced by the state of many arid grasslands around the world.

A biological planning process must be used to coordinate and incorporate the needs of people, plants, animals, and other factors. The typical prescription of lowering stocking rates, changing season of use, and other such commonly used criteria for livestock grazing management have met with little success. It is crucial to understand and work with the natural process that governed the development of arid grasslands. This will require a philosophy that is flexible in terms of stocking rates, delineations of grazing areas, season of use, and the ability of managers to change plans easily and frequently in response to monitoring data and weather patterns.

288