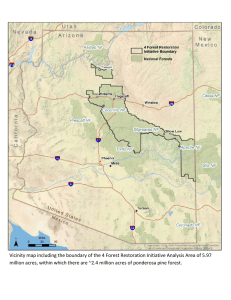

A Historical Review Introduction

advertisement