Relationship of Research to Management in the Madrean Archipelago Region and

advertisement

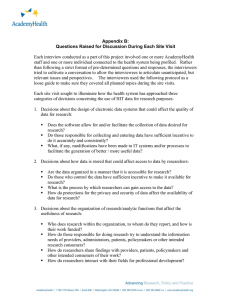

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Relationship of Research to Management in the Madrean Archipelago Region Peter F. Ffolliott1, Leonard F. DeBano2 , and Alfredo Ortega-Rubio3 Abstract.-Our purpose is to provide a context for answering the question: How this conference can address the relationship of research to management of ecosystems in the Madrean Archipelago region? We hope that the linkages between research and management, necessary to meet people's needs while maintaining biophysical integrity, will be viewed as a circular process. That is, much effective research is formulated in response to people's desires for implementing better management, and (in turn) better management frequently evolves from the infusion of the new findings. To place the linkages between research and management into a perspective for the participants of this conference, we present a conceptual model of the main sectors of the Madrean Archipelago (population, agriculture, industry, natural resources, and pollution), which are linked by a web of feedback loops representing transfers of knowledge and technology obtained from researchers and managers. We believe this representation provides a useful tool for attempting to understand where we have been, where we currently are, and where we should proceed in the future to ensure that the concerns of people are addressed properly in relation to the unique characteristics of the Madrean Archipelago region. It is imperative that researchers, managers, and all of the other stakeholders work together in developing a mutu~1 trust in understanding and managing the resources in question. INTRODUCTION Science, as used here, represents the possession of knowledge attained through study (research) and practices (management). Therefore, researchers and managers are scientists. It is our view that scientists should enter into a compact of trust with all the other interested stakeholders in the advancement of knowledge. Unfortunately, researchers, managers, and environmentalists in the Madrean Archipelago are occasionally at odds on the direction that science should take. Much of this disagreement can be traced to differing environmental philosophies that people possess. A problem from a theoretical standpoint has been the conflict between what have been called the IIbiocentrism" and anthrocentrism" schools of thought. The biocentrists assert the need to put nature first, and the dire environmental consequences of putting human needs first (Hays 1992), while anthrocentrists argue that human needs take precedence over environmental concerns, Biocentrists have gained a fair amount of public- The intent of this conference is bringing together researchers, managers, and all of the other stakeholders in the Madrean Archipelago-the area in the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico where scattered, isolated mountains are found in a sea of largely evergreen woodlands-to address a wide array of issues relating to conservation and sustainability of the region. One key to the success of the conference, therefore, is adequately addressing the relationship of research to management of the represented ecosystems, That is the purpose of this paper. II 1Professor, School of Renewable Natursl Resources, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona. 2Supervisory soil Scientist, USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Tucson, Arizona. 3Director, Terrestrial Biology Division, Centro de Investigaciones BiologicBS del Noroeste, S.C., La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico. 31 research is to develop new alternatives (practices, tools, concepts, products, services, etc.) for managers. Another purpose is to answer questions of fact that arise in the management process. A third is to answer questions of fact that arise in cond ucting research, since all to often these basic questions must be answered satisfactorily before the first two purposes of research can be addressed efficiently. Many researchers do not provide information directly to managers. Some provide information to solve the problems of other researchers. Research, therefore, can be viewed as a continuum with the manager at one end of the spectrum. Managers are concerned principally with stakeholders' problems. When managers lack the information needed to help evaluate stakeholders' alternatives, they often "experiment" with these alternative approaches until a "satisfactory solution" is obtained; many managers, therefore, become "surrogate" researchers in the process. Next on the continuum are researchers who are attempting to answer managers' immediate questions of fact, for example those focusing on resource-use trends, prices, and technologies. Following these are the" developmental researchers," who create new alternatives for the managers that will help solve both immediate problems and those yet to be formulated. Further along the spectrum are the researchers who serve a clientele of other researchers. These researchers typically come from the basic disciplines, providing the facts, relationships, and other inputs needed by those who conduct the "more applied" developmental research. Although the ultimate clients for all researchers and managers are the other stakeholders, it can be seen that the intermediate clientele can be managers or other researchers. Successful problem anticipation and, as a consequence, planning become more difficult as the distance on the spectrum between researchers and managers increases. While researchers focus on their immediate clients in many instances, even their most basic activities usually are intended to help solve management problems. Research planners, therefore, need to anticipate these problems accurately and articulate their contents appropriately. Information necessary for the solutions of the problems comes from managers, environmentalists, and other members of society who are stakeholders in the enterprise. To the extent that information comes from all these sources, it confirms the premise put forth earlier in this paper that research and management should be viewed as a circular process. ity in the popular press, but have not always affected the cause of environmental action to the extent that they have hoped. To protect natural systems from development, they often adopt the pragmatic action of finding ways for public or private bodies to insulate an area from the private market to "save" it. While the basic philosophical issues of this discussion are important, a more productive approach for this conference may be one advanced by Norton (1991). He believes that the dominant reason for environmental actions should be practical, pragmatic, and focused on problem-solving. He also believes that interested stakeholders waste much time and energy, and foster unneeded tensions, by arguing the merits of the biocentric view as epitomized by John Muir in relation to the use-oriented tradition of conservation exemplified by Gifford Pinchot. It is more important, Norton continues, that all of the stakeholders focus on practical situations in which those who are at odds on some philosophical points can work out mutually acceptable solutions to problems. ROLES OF RESEARCHERS AND MANAGERS The roles of researchers and managers in relation to the consumptive and nonconsumptive uses of resources in satisfying human desires have been articulated nicely by Stoltenberg~t al. (1970) among others. In general, resource managers assist individual and societal stakeholders in a number of ways. Managers help stakeholders identify and clarify their objectives. They also identify for the stakeholders the alternative approaches to achieving their objectives, and help them to evaluate or compare these alternatives, selecting the most promising opportunities for achieving the stated objectives. Managers frequently spend a disproportionate part of their time supervising subsequent activities to implement these decisions, however, and have insufficient time to emphasize problem-solving efforts. This situation is unfortunate, because managers often are making their most valuable contributions helping stakeholders make decisions, Just as a manager's contributions are measured by how effectively they help stakeholders satisfy their wants, the value of resource researchers is determined largely by how much their efforts increase the efficiency of the managers (Stoltenberg et al. 1970). One purpose of 32 A PERSPECTIVE ON THE IMPORTANCE OF RESEARCH AND MANAGEMENT IN THE MADREAN ARCHIPELAGO REGION therefore, the flows of these resources depend largely upon the level of industrial capital targeted for their exploitation. Industry and agriculture both generate pollution, and severe pollution affects both people (by reducing their health) and their food sources (by reducing agricultural yield). Effective research followed by responsive management are necessary in assuring that all of the feedback loops connecting the sectors are identified properly, the flowlines are comprehensive in content, and the flows into and out of the reservoirs are effective, efficient, and appropriate. Attaining these assurances should be a major goal of researchers and managers in the Madrean Archipelago region. To this end, we hope that this conference provides a forum for the participants to evaluate where we have been, where we currently are, and where we should proceed in the future in meeting this important goal. The representation shown in figure 1 is a simplified model and not intended to be all encompassing. It is obvious that much has been left out of this simplified version. For example, all of the resources that drive industries (metals, energy, foodstocks, etc.) are amalgamated into a single feedback loop. Similarly, all of the pollutants (human, agricultural, and industrial wastes) are represented by one loop. And, importantly, there is no representation of geographical inference in the model. The peoples in both the A perspective on the importance of effective research and responsive management in the Madrean Archipelago region can be gained, we believe, through a recognition of the dynamic nature of the systems encountered. The conceptual model in figure 1, originally constructed by Meadows et al. (1972) to represent the limits to growth on a world-wide scale, illustrates how population, agriculture, industry, natural resources, and pollution in the Madrean Archipelago are linked together by a web of multiple feedback loops. These feedback loops represent transfers of the "products" of knowledge and technology from one sector to another and, therefore, are largely the combined products of research and management. While other models may apply equally well, this model was selected because it is structured in a format that depicts the Madrean Archipelago region, and contains the sectors important to the people of the region. Most of the linkages in figure 1 suggest interdependence of the sectors represented (population, agriculture, etc.). Agriculture and population, for example, have an obvious interdependence in that more of one implies more of another. Industry dependents on needed inputs of nonrenewable resources (ore, fuels, etc.), and, r-------~.c.HE'l'S ON H E A L T H - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - , . . - - - - - H H C T S ON YlELD------------------.. ,--------SOO])5 ;lND 5 E R ' , ' I C E S - - - - - - - - - . , I I !I ,+, I I f !oljr!-~i ; POPUL4rION 1 I DiJe lION i I ! ! !, ;-----,~:;,tl !'hUH: I : . L S - - - - . t'-----' N,QIURHL IlGRI CULTURE RISOORCES t ' - - - - - - - , , < 1 \ RH I NS----.J 1 . - - - - - - - - - - r.. F'OLLUIIOft ! I ! 1 AEOJ:-I-------'1 ~ I '------------..;i;\STE--------' I I II I' - - - - - - - - i 1 ; i S T E - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - i ' - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - . . ; I A S H SJ I Figure 1.-linkages of population, agriculture, industry, natural resources, and pollution in the Madrean Archipelago region (adapted from Meadows et at 1972). 33 all of the ecological processes that link them together) that has importance beyond traditional commodity and amenity uses (Kessler et al. 1992). With this view, management practices that optimize the production or use of one or a few resources can compromise the balances, values, and functional properties of the whole. Furthermore, the production or use of individual resources in themselves might not lead to sustainability. Objectives of the ecosystem approach relate to the ecological and aesthetic conditions of the landscape, and sustainable levels of land uses and resource yields that are compatible with these conditions. In some respects, these objectives reflect the earlier concept of "area-oriented" multiple use management, in which the information needed to describe resource potentials is drawn from "resource-oriented" multiple use. This information is then arranged, analyzed, and evaluated in spatial relation to a given land area's suitabilities for management, and the dynamics of local, regional, and national demands of the people (Ridd 1965). Current conflicts in resource management indicate that the roles of public participation in relation to endorsing management practices are changing, regardless of the paradigm. Stakeholders' roles in the past have been largely to respond to professionally prescribed alternatives that estimate outputs of management in terms of cords of fuelwood, animal-unit months of grazing, recreational user-days, or breeding pairs of Mexican spotted owls (Kessler et al. 1992). Tradeoffs have been presented as changes in the quantities of one resource use in relation to the others. The production-oriented multiple use management of the past no longer reflects the thinking of many people in the Madrean Archipelago. People are not only thinking about optimizing the levels of competing uses through management, but also obtaining a harmonious relationship with the rest of the natural system, in contrast to a view favoring people's dominance over nature (Norton 1988). It is important, therefore, that researchers and managers develop approaches that better fit the way people think about land and resources in today's world. Stakeholders must become informed about the conditions, capabilities, and options for their lands and resources, and share the knowledge that professionals accrue through the research and management experience (Kessler et al. 1992). At the same time, researchers and managers must understand and consider the values and needs of people, rather than concluding southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico are one-as perhaps they should be considered in this conference. CONSERVATION AND SUSTAINABILITY IN THE MADREAN ARCHIPELAGO REGION Researchers and managers in the Madrean Archipelago, along with researchers and managers throughout other regions of the United States and Mexico, face changing expectations on how limited resources should be used to meet people's needs. Managerial strategies, scientific knowledge, and technology necessary for producing the traditional multiple uses of resources only partially satisfy stakeholders' interests in the use of resources in the 1990s. Researchers and managers, therefore, must become increasingly responsive to the more demanding viewpoints that stakeholders have of these resources and their respective roles in meeting people's desires. Such a perspective embraces a stewardship that balances the protection of natural environments and a sustainability of products and services needed by people (Kessler et al. 1992). There is little question that the multiple use philosophy of management served society reasonably well into the 1980s. Lands were characterized largely in terms of their capacities to yield commodities and amenities. A primary role of research at this time was discovering the factors that limited the realization of these capacities, while a key objective of management was reducing or removing these limitations. Answers to questions about resources required the identification of "optimum yields" among the desired (and often competing) uses (Kessler et al. 1992). However, multiple use is not necessarily the best way to approach management when stakeholders begin to ask far-ranging questions on how to balance a wide range of potential uses and values, which is the situation in the Madrean Archipelago today. An alternative paradigm, one embracing an "ecosystem approach," has been proposed by the National Research Council (1990) for the management of forest lands. We suggest this ecosystem paradigm applies equally well to many of the lands and resources in the Madrean Archipelago, The ecosystem approach modifies and broadens the multiple use paradigm to one of holistically conceived ecosystem management. It requires one to view lands in a comprehensive context of living systems (including soils, plants, animals, minerals, climate, water, topography, and 34 the varied social and economic objectives involved, the heterogeneity of the stakeholders and organizational structures, and the cultures of the people involved. All of these topics will be considered in the conference. what is good or bad for society from their own, often technical, perspectives. It should be obvious that new thinking about resources, people-nature relationships, and sustaining ecosystems is required in the scientific communities of the Madrean Archipelago. The resulting changes, when they occur, will likely be reflected by a trend where the traditional basic and applied disciplines come together in seeking solutions to the problems of conservation, ecosystem sustainability, and people's welfare (Christensen 1989, Murphy 1990). The activities of this conference should encourage such a trend. LITERATURE CITED Christensen, P. 1989. Historical roots for ecological economics: Biophysical versus allocation approaches. Ecological Economics 1:17-36. Hayes, B. 1993. Balanced on a pencil point. American Scientist 81 :510-516. Hays, S.P. 1992. Environmental philosophies. Science 258:1822-1823. Kessler, W.B.; Salwasser, H.; Cartwright, C.W.; Caplan, J .A. 1992. New perspectives for sustainable natural resources management, Ecological Applications 2:221-225. Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J. Behrens III, W.W. 1972. The limi ts to growth: A report for the CI ub of Rome's project on the predicament of mankind. Universe Books, New York. 131 p. Murphy, D.D.1990.Conservation biology and the scientific methods. Conservation Biology 4:203-204. National Research Council. 1990. Forestry research: Amandate for change. National Academy of Science, Washington, D.C. 84 p. Norton, B.G. 1988. The constancy of Leopold's land ethic. Conservation Biology 2:93-102. Norton, B.G. 1991. Toward unity among environmentalists.Oxford University Press,NewYork.287p " Ridd, M.K.1965. Area-oriented multiple use analysis. Res. Pap. INT-21. Ogden UT: u.s. Department of Agriculture, USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range ExperimentStation.14 p. Stoltenberg, C.H.; Ware, K.D.; Marty, R.J.; Wellons, J.D. 1970. Planning research for resource decisions. The Iowa State University, Ames,IO. 183p. CONCLUDING COMMENTS A frequent debate that we have all heard is whether a big conference such as this is useful and effective in comparison to a smaller symposium that addresses specific topics. We are convinced, however, that this conference, while "big" to some people, will play an important role in planning for the future of the Madrean Archipelago that could not be filled by smaller symposia on more specific, often limited subjects. This conference will highlight many of the recent, continuing, and planned efforts of the research and management communities in the region that will facilitate communication among people of previously diverse interests. The potential will be established for the researchers, managers, environmentalists, and other stakeholders participating in this conference to cooperate in a setting characterized by mutual interests, principles, and knowledge. For this to happen requires a recognition of the ecological characteristics of the resource base, the level of ecological knowledge held by the stakeholders, 35