Occurrence and Control of Piiion ... Alligator Juniper, and Gray Oak ... and Seedlings Following Fuelwood Harvest

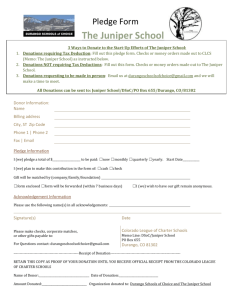

advertisement

Occurrence and Control of Piiion Pine, Alligator Juniper, and Gray Oak Sprouts and Seedlings Following Fuelwood Harvest M. Karl wood' and Roxanne scanlonZ - Abstract Three experimental plots (12 x 25 meters) were located in each of four blocks (12 total plots) on a uniform southwestern exposure. Four of the plots were left undisturbed as controls. Four of the plots were clearcut in June 1989 and burned 4 months later in October I989 (Treatment 1). Four of the plots were clearcut in June 1989 and burned 28 months later in October 1991 (Treatment 2). In July 1992, sprouts and seedlings were counted and heights measured in each plot. None of the piAon pine stumps sprouted, 47% of the alligator juniper stumps sprouted, and 90% of the gray oak stumps sprouted. Treatment 1 resulted in 50% of the alligator juniper sprouts being killed and none of the gray oak sprouts being killed. Treatment 2 resulted in only 10% of the alligator juniper sprouts being killed and 17% of the gray oak sprouts being killed. The control plots gained the equivalent of eight new alligator juniper seedlings per hectare from seeds by 1992, while the plots in Treatment 1 had no new alligator juniper seedlings, and the plots in Treatment 2 had 17 new alligator juniper seedlings per hectare. The control plots gained the equivalent of 608 new gray oak seedlings per hectare from seeds by 1992, while the plots in Treatment I had 133 new gray oak seedlings, and the plots in Treatment 2 had 492 new gray oak seedlings per hectare. Only 50 mature gray oaks per hectare were found in the control plots, which indicates that most seedlings do not become mature plants. INTRODUCTION Piiion pine and juniper species have similar ecological requirements and tolerances, which allows them to grow as dominants on many rangelands of the western United States. They are usually found as climax species on mky hillsides and invade downhill onto flood plains, piedmonts, and valley bottoms and uphill onto mesa tops. Prior to settlement by Europeans, these invaded lands were burned from wildfiis that killed most of the invading plants. Occasionally, the wildfires missed a plant, which resulted in a widely scattered savannah ' Professor of Rangeland Watershed Management, Range Improvement Task Force and Department of Animal and Range Sciences, New Mexico State University, Las Cmces, NM. Researcher, Department of Entomology, Plant Pathology, and Weed Science, New Mexico State University, Las Cmces, NM. With the cessation of fm,these invaded lands experienced loss of the shrub, grass, and folt, components, which resulted in accelerated erosion of the deep soils in the interspaces between trees. Archeological sites are adversely affected by the erosion and wildlife habitat is lost due to and abundance of tms and a suppression of understory food sources. F a h g to stop the invasion or return the lands to a state of sustainability is a gross violation of the federal Clean Water Act. Programs to control the invaded piiron pine and juniper trees have included burning, mechanical, chemical, biological, and fuelwood harvest methods. Following control, sprouts from stumps and new seedlings rapidly appear, which give a need for follow-up and maintenance to prolong the life of the ori@ control treatment. The objectives of this research project were: 1. To determine the number and height of sprouts and seedlings following fuelwood harvest of a piiron pine and juniper dominated mesa top site Sprout Mortality From Burning 2. To determine the effects of fire for sprout and seedling control Site Location Burning 4 months after clearcutting resulted in 50% of the alligator juniper sprouts being killed and none of the gray oak sprouts being killed. Burning 28 months after clearcutting resulted in only 10% of the alligator juniper sprouts being killed and 17% of the gray oak sprouts being killed. The study was located in a commercial fuelwood harvesting area of the piiion pine -juniper woodland on the edge of Spring Sprout Heights Following Burning METHODS Mesa adjacent to Corduroy Canyon, which are between Winston and Beaverhead in the Gila National Forest. Specific location is Section 36, T9S, R12W, Catron County, New Mexico. The mean elevation is 2245 meters. Soils on the study site are Lithic Haplustalfs. The vegetation of the study area consists of a moderately low tree density of two-needle piiion (Pinus edulis) (440 trees per hectare), alligator juniper (Juniperus deppeana) (167 trees per hectare), and gay oak (Quercus grisea) (69 brees per hectare). The understoxy herbaceous growth comprises a variety of grass and forb species. Among grasses, the most plentiful species is blue grams (Bouteloua gracilis). Mountain muhly (Muhlenbergia montana), wolftail (Lycurus phleoides), and squimltail (Sitanion hystrix) are the other commonly found grasses. Goldeneye (Yiquiera dentata), Bahia spp., and a few chenopods are some of the eyecatchmg forbs in the area. Treatments Three experimental plots (12 x 25 meters) were located in each of four blocks (12 total plots) on a uniform southwestern exposure. Four of the plots were left undistuhd as controls. Four of the plots were clearcut in June 1989 and burned 4 months later in October 1989. These plots had experienced one growing season to obtain favorable understory response, and the slash was dxy. Four of the plots were clearcut in June 1989 and burned 28 months later in October 1991. These plots had experienced three growing seasons which resulted in much more favorable understory response but also taller sprouts. The purpose of the burning was to control stump sprouts. In July 1992, sprouts and s e m were counted and heights measured in each plot. RESULTS Burning at 4 months after clmutting resulted in shorter alligatorjuniper sprouts at 36 months postclearcut than alligator juniper sprouts that were allowed to grow for 28 months Qable n t Gray oak sprout 1). The difference was a ~ i g ~ c a 59%. heights were not si@cantly different at 36 months when burned at 4 months after clearcutting and 28 months after clearcutting. - Table 1. Sprout heights (crn) 36 months after clearcutting for fuelwood. Control Burn at 4 months after clearcut Burn at 28 months after clearcut Pinon pine 0' 0 0 Alligator juniper 0' 22 35 Gray Oak 0' 94 89 ' No stumps present Seedling Density Most new seedlugs occurred in the control plots (Table 2). In all three treatments, gray oak seedlings were the most common Burning at 4 months after clearcutting resulted in no new piiion pine and alligator juniper seedlings while burning 28 months after clearcutting resulted in sigruficantly more than burning at 4 months. - Table 2. New seedlings (number per hectare) 36 months after clearcutting for fuelwood. - - -- pinon pine 33 Burn at 4 months after clearcut 0 Alligator juniper 8 o 47 608 133 492 Sprouting None of the pine stumps sprouted, 47% of the alligator juniper stumps sprouted and 90% of the gay oak stumps sprouted. This experiment was spatially replicated but not temporally. Because 1989 was a drought year, these percentages may be lower than sproutmg percentages in wetter years. - Control Gray Oak Burn at 28 months after clearcut 8 Seedling Heights Following Burning Piilon pine seedhg heights were 77% greater in the controls and 64% gmter in the burn at 28 months after clearcut treatment than alligator juniper seedlug heights ( T ' l e 3). Heights for all species increased with time to bum, and seedltng heights in the treatment that was burned 28 months after clearcutbng were sigmficanfly greater than the controls. - Table 3. New seedling heights (cm) 36 months after clearcutting for fuelwood. Control Burn at 4 months after clearcut Burn at 28 months after clearcut Pinon pine 16 0 46 Alligator juniper 9 0 28 Gray Oak 17 28 37 CONCLUSIONS Piilon pine did not sprout after clearcutting. Half of the alligator juniper stumps sprouted, and most of the gray oak stumps sprouted. The highest mortality of alligatorjunipers (usually a desirable goal) and the lowest mortality of the gray oak (also usually a desirable goal) is best achieved 4 months after clearcutting. But a companion study showed the understo~yhad not responded enough in the first growing season to adequately protect the site from erosion following burning. Therefore, buming to control sprouts was not found to be favorable. Burning was not a useful tool for controlling alligator juniper sprouts. Alligatorjuniper sprouts grew faster than new seedlings. OTHER CONSIDERATIONS Re-establishment of piiion pine, if desirable, might be accomplished by leaving a branch attached to the stump. Unwanted sprouts and seedling may be individually controlled with herbicides where permissible. Or they might be controlled by individual treatment with flammable liquids when fuel conditions are so wet that gmses and forb will not burn.