and Managing Southwestern Piiion- Juniper the Future

advertisement

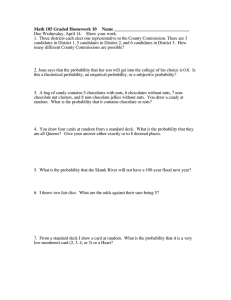

Managing Southwestern Piiion-Juniper Woodlands: The Past Half Century and the Future Elbert L. Little, ~ r . ' - Abstract The dominant species in southwestern pinon-juniper woodlands is pilion or twoleaf pilion (Pinus edulis Engelm.). Though productivity is low because of low precipitation, this type is very important because of its vast acreage and increasing demands. A great change in management during the 1950's and 1960's was eradication of trees on several million acres. Subjects of high priority among the research needs for managing southwestern pinon-juniper woodlands include: preparation of a new bibliography; a new forest survey or inventory; annual pifion nut forecasts; establishment of small pifion arboretums or orchards; a new economic analysis; harvesting pinon nuts; shelling pinon nuts; and marketing pinon nuts. The lively discussion on research needs suitably ended this Symposium. Interested persons can look forward to additional symposia and the valuable volumes with summaries of m n t research. I wish to share my unique opportunity to obseme piiion-juniper woodlands in southwestern United States for more than a half centuxy, after four years of basic field research there (1937-41). Several subjects of high priority among the many research needs proposed at the Symposium will be discussed here. This article follows mine at the 1991 Symposium (Little, 1991). The dominant species in the piiion-juniper woodland of New Mexico and Arizona, piiion or twoleaf p h n (Pinus edulis Engelm.) is associated with four species of juniper (Juniperus). In the Great Basin of Utah, Nevada, and eastern and southern California, singleleaf piiion (Pinus monophylla Ton: & Frdm.) is dominant. This mar@ woodland of small evergreen conifers occupies an altitudinal climatic zone below the commercial humid forests of pines and other conifers in high mountains and the semiarid grasslands and shrub vegetation of low plains. The term juniper-paon woodland is also appropriate, because junipers extend beyond pifions to great expanses in the Northwest. These two distinct species are the only pine species native in the United States that are commercially important for their edible seeds. They differ in forest management as well as ' Dendrologjst (retired), USDA Forest S e ~ c e Washington, , D.C., and Research Associate, Dept. of Botany, Smitbsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. in nuts commercially, such as size, shell thickness, and taste. The small nut of Pinus edulis high in oil content produces a taste suggesting bacon when toasted and is preferred by most persons to the mealy nuts of other species. Two to four other species of piiions native in southwestern United States have small ranges and produce no commercial nuts. This marginal piiion-juniper woodland type is of low productivity because of low precipitation. However, it is very important because of its vast acreage and increasing demands from expandmg local populations. Under multiple use, piiIon nuts are a valuable renewable natural resource. "Managmg woodlands for piilon nuts" was the title of a botanical note published more than a half century ago (Little, 1941). Progress has been slow. Durrng and soon after World War 11, pifion nut harvests declined somewhat, apparently because of shortage of pickers. Eradication of several million acres of woodlands, discussed below, reduced harvests. Now, annual harvests appear to be back to normal. In the United States, p&n (mostly Pinus edulis) is the native nut of greatest economic importance for its harvest from wholly wild trees, Because of low values and high costs, introduction into cultivation of this small tree of slow growth adapted to semiarid regions seems impractical. Pifion should not be compared with pecan (Carya illinoensis (Wangenh.) K. Koch), another native tree of humid regions widespread in cultivation and even inigated in southern Arizona However, slight incmse in piiion nut production may be possible through management of wild trees on good sites. Silvicultutal treatments include thinning by removal of less productive trees, pruning, addition of chemical fertilizers, and control of runoff water through ditches to trees, Possibly, superior tree seedlings could be planted in openings, though commercial nut production may be 75 or more years distant. Watershed and Air Management is the staff in which piiion-juniper woodlands on National Forests in the Southwest have been placed. The first goal of management of wild lands is soil conservation, including saving topsoil, reduction of accelerated erosion, control of flood waters, and improvement of water quality and yield. I learned this principle in two years (1935-37) of watershed management research at Sierra Ancha Experimental Forest (Parker Creek) on the Tonto National Forest in central Arizona. Much erosion control was accomplished by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the decade beginning in 1933. Some gullies still may need erosion control by rock check dams and piling of brush. Reduction in numbers of livestock may be desirable where grazing is heavy. The great change in management of piflon-juniper woodlands during the 1950's and 1960's was eradication of trees on several million acres of better sites on the National Forests and other public lands over the Southwest and Great Basin regions (Arnold, Jameson, Reid, 1964). The case against eradication has been summarized by Eanner (1981, Ch. 12). "Broken Treaty at Battle Mountain," the film narrated by Robert Redford A d shown at this Symposium, vividly records the destruction of large junipers by chaining. The false, unscientific excuse was that this eradxation was "control" of "invasion." However, this woodland is a climatic climax type, and the mature trees destroyed were one or two centuries old, not invaders of grasslands. Two questions are whether this conversion was cost effective and whether it is temporary. Junipers have invaded some areas of grasslands following grazing by domestic livestock. However, reports of invasion by piiions probably refer to reestablishment of piiions in areas cut for mine timbers and fuelwood long ago. Any future proposals for clearcutting and conversion should have thorough review, including preparation of environmental impact statements and approval by conservation groups. Continuing assurance is needed from land managers that some piiion-juniper woodlands will be managed for multiple use includmg piiion nuts. Further eradication of piiion, New Mexico's state tree, on public lands must not be permitted! Convetsion was the subject of a detailed study by the USDA Forest Service on the Beaver Creek watershed in central Arizona. It was concluded that removal of piiion-juniper did not increase water yield (Clw, Baker, O'Connell, 1974). The question of fire in management of piiion-juniper woodlands used partly for livestock grazing has been raised in recent years. Genedy, fm damage to mes has been minor because of their wide spacing, especially at lower altitudes. No burning (with rare fire outbreaks) usually is preferred over uncontrolled fire. However, at higher altitudes, the tree stands may become dense for forage and piiron nut production. More research is desired to determine whether prescribed burning is practicable on lands managed under multiple use. A new bibliogaphy or compilation of new references on piiions and junipers is b u d , though numemus publications during the past half cenhuy are listed in bibliographies and cited in symposium volumes. Three publications available at this Symposium merit specla1 mention Lanner (1981) has p q a d an interesting natural and cultural histo~yof piilon with a detailed bibliography. ccSSva of North America" contains chapters on Pims edulis by Ronco (1991) and Pims mnophylla by Meeuwig, Budy, and Everett (1991), both with literature cited A new forest survey, inventoIy, or compilation of public lands in the Southwest is needed to determine ownership, composition, areas of potential piiion nut production, present management, and future plans. Areas eradicated and converted into grasslad should be mapped as excluded fi-om piiron nut production Annual piilon nut forecasts should be published, based on summer surveys of public lands in the Southwest to locate areas with commercial cone crops. These informal surveys to aid pickers began in 1938 were continued for about ten years. There is a commercial crop of piiion nuts somewhere in the Southwest eveIy autumn. The simplest way to increase the harvest is to pay the pickers more. Of lower priority is forecast of cone crops two years in advance by correlation with weather conditions in late summer, the time of formation of earliest microscopic stages (primordia) of cones. Small arboretums or orchards of piiions and other nut pines should be established in both New Mexico and Arizona to determine the best adapted species and varieties. These could be small groves near ranger stations. The only similar collection of living piiions is at the Institute of Forest Genetics, USDA Forest Service, near Placerville, CA. Those trees have borne cones and have been crossed. (I brought fresh specimens to the Reno Symposium, Jan. 1986.) If I had started similar groves 55 years ago, the trees now would show differences in xate of growth and adaptation A new economic analysis of the piiion nut industry is desired. Subjects to be Mewed include fees charged to pickers, methods of harvesting piilon nuts, shelling piilon nuts, marketing including packaging and advertising, and competition from imported nuts. Hawesting piiion nuts needs further study. At present, the Bureau of Land Management charges pickers a small fee per pound for nuts of slngleleaf pifbn in the Great Basin region. The USDA Forest Sewice has no similar fees. Harvesting of Pinus monophylla is by closed cones in the trees in early autumn, as illustrated in the film showed at the Symposium, "Broken Treaty at Battle Mountain," narrated by Robert Redford. Most harvesting of Pinus edulis is by individual seeds on the ground with fingers of both hands. At 1 seed a second and up to 1800 seeds in a pound, a person can pick up to 2 p o d s an hour where nuts are thick, not includmg travel time or cost. Hawesting of mature closed cones could be tested during the month of September and perhaps end of August. Incidentally, these cones are very resinous or sticky, but the resin can be removed with powdered borax mixed with water as needed. During the month of October the cones (with resin) dry and open their scales to shed the seeds by gravity. Then the seeds can be picked from the ground until winter or until harvest by wildlife. Pinus edulis has smaller cones than Pinus monophylla, with fewer, smaller nuts, roughly 20 to a cone. Most closed cones could be picked with a pruning pole or hook or from a stepladder or longer ladder, though tree climbing could be tried. Raking or sweeping the nuts on the ground into piles could be followed by sifting with a frame of coarse screen, then rescattering of litter. Before the nuts fall, a plastic sheet could be placed on the ground, and then the branches beaten with poles or shaken to release the seeds. (A small truck with bucket 11% suggested in one article, seems impractical on rough ground as well as expensive.) My suggestion is to develop a portable vacuum cleaner to pick up nuts from the ground.A rechargeable battery and a screen to sepamte out most needle litter and trash would be needed. A machine for shelling piiion nuts was invented by one dealer in Albuquerque in the 1930's. After the dealer's death, this machine was acquired by another local company. Similar shellers could be adapted from those for other nuts and seeds or for pine nuts in other countries. Some imported nuts may be shelled partly by cheap hand labor. The simplest way to crack nuts of Pinus edulis with the teeth or a hammer is by pressure from the ends. The shell collapses and breaks into pieces without damage to the nutmeat. One nut cracker sold for home use has the shape of the letter V and grooves for holding a nut with thumb and finger while pressure is applied. At the 1991 symposium I described and demonstrated the Little Pifion Nutcracker (Little, 1991). It consists of pliers with a block of wood about 318-112 inch square and about 1inch long (or 2 short pencils) fastened within by a rubber band. The nut held between thumb and finger is cracked by pressure from closing jaws f pliers. Studies in marketing, including packaging and advertising, can be done by specialists in those fields. Piiion nuts, among the smallest of commercial nuts and a wholly wild crop, cannot be produced as cheaply as commercial nut crops. For example, peanuts are harvested in billions of pounds annually, instead of millions, at much lower costs and with government subsidy to growers. M o n nuts have three main markets: local residents, tourists, and luxuty nut stores, such as at airports. Irregularity of pifbn nut crops is a problem in marketing, involving storage and treatment as a commodity to obtain loans and to keep prices stable. As noted before, there is a commercial crop of pifion nuts somewhere in the Southwest every autumn. Also, the simplest way to i n c m e the harvest is to pay the pickers more and thus increase retail prices. However, estimates of the crop not harvested seem high. A light crop is eaten by insects and wildlife ahead of humans. Also, within a few months after maturing, pifion nuts lose about a fifth of their weight in water loss or shrinkage. "Pine nuts (Pinus) imported into the United States" is the subject of my other paper at this symposium. At present, unshelled pine nuts are imported in relatively small quantities. Shelled nuts are imported in increasing quantities about equal to native production. Competition may become serious. Recently in Israel I saw a small plantation of Italian stone pine (Pinus pinea L.), the commercial pignolia of subtropical southern Europe, there slightly outside the natural range. The wingless seeds have a thick shell too hard for cracking with the teeth A sample bought in a nearby town apparently was shelled by hand. The local name from French pignon is pronounced like piiion Incidentally, Israel no longer tests this pine in forests and has no nuts for export. A new forestry monograph of this species is by two Ita&ms, Agrimi and Ciancio (1992). LITERATURE CITED Agrimi, M.; Ciancio, 0 . 1992. Le pignon (Pinus pinea L.). Quinzieme Session du Comite CFFSAICEFICFPO des Questions Forestieres Meditemennes, Silva Meditema, Faro (Portugal), 18-20 mars 1992. 52 p. Arnold, Joseph F.; Jarneson, Donald A.; Reid, Elbert H. 1964. The paon-juniper type of Arizona: effects of grazing, fire, and tree control. USDA Forest Sewice, Product Research Report, 84 28 p. Clary, Warren P.; Baker, Malchus B., Jr.; O'Connell, Pad F.; and others. 1974. Effects of pifion-juniper removal on natural resource products and uses in Arizona. USDA Forest Service, Research Paper RM-128, 28 p. Lanner, Ronald M. 1981. The pifion pine: a natural and cultural history. 208 p. University of Nevada Press, Reno. Little, Elbert L., Jr. 194 1. Managing woodlands for pifion nuts. Chronica Botanica 6: 348-349. Little, Elbert L., Jr. 1991. Piiion (Pinus edulis): an overview. P. 72-76. In: New Mexico State University, Proceedings-199 1 piiion conference April 23, 1991. Santa Fe, NM. Meeuwig, R. 0 . ; Budy, J. D.; Everett, R. L. 1991. Pinus monophylla Ton. & Frem. Singleleaf piiion. P. 380-384. In: Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H., tech. coord. Silvics of North America. USDA Agriculture Handbook 654, vol. 1. Ronco, Frank P., Jr. 1991. Pinus edulis Engelm. Piiion P. 327-337. In: Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Baxbara H., tech. coord. Silvics of North America. USDA Agriculture Handbook 654, vol. 1.