Strategic Riparian Resource Management

advertisement

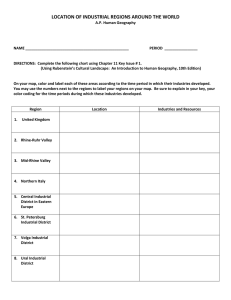

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Strategic Riparian Resource Management in a Metropolitan Setting: The Minnesota Valley Experience 1 Tim Kelly 2 Abstract.--Riparian lands in metropolitan areas are often under extreme pressure to accomodate conflicting uses. Strategic management planning provides a method for mediating conflicts, and developing realistic objectives. This paper discusses the performance, pitfalls, and potential of the strategic management effort for the Minnesota Valley National Wildlife Refuge and Recreation Area. allowance for unexpected developments and thereby not allow managers of riparian lands to act in the most opportune ways. INTRODUCTION Effective Management of Riparian lands often suffers from the manner in which the planning for those lands is done (Bailey, 1982). The perspective taken is that it is not the plans that are bad, necessarily, but it is the way plans are done that could stand improving. The bias here is that doing planning "right" is more important than making a technically correct plan. Planning Hierarchy One approach useful in resolving this problem is to distinguish three levels of planning. The first level is product design planning (planning for the type, extent, complexity and apparentness of facilities or modifications to the resource). The second level involves operational planning (planning for capital, labor, and application of technical programs such as burning or visitor information). The third level is strategic planning (planning for the uncertainties and contraints facing a management effort). Planning techniques and analytical formats for resource management decisions are available in profusion - models, simulations, standards, etc. They could stand further technical refinements, surely, but line management performance is often little affected by doing so(King, 1972). Product design and operation plans are specialized, narrowly focused plans. They may detail methods and goals that largely are given with such constraints as site capability, personnel availability, engineering specifications and program prescriptions. As a result these plans are often detailed and quite complex. In strategic planning, the constants for these two previous planning efforts become variables which direct and potentially change the way the agency pursues its basic missi.on; however, operations and the products they oversee, is the way the mission is pursued. Techniques often have an unhappy way of seeking an application. They can become solutions looking for problems. The result is often either a plan that collects dust on the shelf or one that is overly rational, where all possible actions are guided toward predetermined goals. The paralysis of analysis thereby creeps in. A weakness of such an approach to planning and management is that it may not make Strategic Management Planning 1 Paper presented at the Riparian Ecosystems and their Management Conference [Tucson, Ariz., April 16-18,1985]. 2 Senior Planner, Natural Resource Planning, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, St. Paul, Mn. Many people have been helpful in developing the ideas for this paper, most notably, Julie Kelly, Glenn Radde, Brian Stenquist, and Paul Swenson of the Minn. DNR; Ed Crozier and Jim Lutey of the U.S. FWS; and Arnie Stefferud of the Metropolitan Council. It should not be assumed that the stategic plan is the arithmetic sum or five yea.r extrapolation of particular product and operation plans. Strategic management planning is a different planning process, with very different purposes, constraints and givens and hence different inputs from those of functional plans. Strategic management planning involves identifying key issues which relate to 403 the capability of operational activities and product areas to succeed, so that those activities 'can be related to the physical, social, and managerial environments in which they exist (Steiner, 1979). Second, that the proposed courses of action responded to the interests and values involved, and that tradeoffs were reasonably fair. Third, that credible two-way communication between the project and the various interests was established in order to find ways to mediate and negotiate problem issues. There are four elements to a strategic management situation which must be addressed either explicitly or implicitly for strategic planning to yield effective results (Steiner, 1979). These are the expectations of the major interests outside of the organization, the expectations of the major interests inside the organization, the history, condition and trend of the resource as it relates to management performance, and the organizational strengths/ weaknesses, and the opportunities/threats in its environment. If one of these elements is missing, the management system created by the plan will not operate effectively. The result will be confusion and/or skepticism on the part of management and the public. Conservation efforts in the lower Minnesota River Valley have a long history of citizen involvement. Both the state trail and the refuge/recreation area were initiated and carried through the legislative process by citizen organizations. A number of private interests such as private hunt clubs stable-s and nature centers have been involved in promoting and taking advantage hf the recreational and wildland potential of the area. Most of the economic activity involves sand and gravel extraction, barge transportation of grain, and development. In total over 225 meetings and workshops were held with individuals, groups and the public. Support for the project focused on the desire for public access and use, preservation of wildlife habitat, and the continuation of traditional uses such as hunting and trapping. Expectations and attitudes resistent to the refuge and recreation area concept were the potential loss of family farms, the lock up of exploitable sand and gravel resources, and potential restrictions on residential and commercial development. This paper reviews and analyzes the strategic management planning effort for the Minnesota Valley National Wildlife Refuge and Recreation Area in light of these four elements. It should be pointed out, however, that in reality the planning process was iterative, involving continual back and forth analysis. PROJECT SETTING The Minnesota Valley National Wildlife Refuge and Recreation Area was establj_shed in 1976 to recognize the values of wildlife habitat preservation, environmental education and close-to-home recreation (P.L. 94-466). The area involves 19,110 acres along the lower 36 miles of the Minnesota River. Agency Perspectives An essential step to developing effective strategy is also determining the interests of key managers and administrators within the management framework. Many of these values can not be evaluated quantitatively or logically but do influence basic long range aims and objectives of an agency or program. One of the most important elements in the planning process of the valley was coordination of the counties and municipalities. Local government exerts the most direct influence over the land uses of the valley. Without their assistance, the incremental effect of land use development decisions could make management of project lands for wildlife or recreation impossible. In addition the amount of coordination and cooperation required within and between agencies required contact with key people within the two lead agencies. In the final analysis support for the project took the form of agreement that something should be done to protect the natural character of the valley. Opposing this was resistance to a project that was very different from traditional wildlife refuges and state parks in its shape and required administration. The Flood Plain of the Minnesota contains an almost continuous belt of type III an IV wetlands and shallow lakes, as well as wet prairie and floodplain forest. MorP than two million people in the Minneapolis-St. Paul Metropolitan area live within a half-hour of the refuge and recreation area. The sixteen management units involve 38 government units including four counties and nine municipalities. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources were the lead agencies charged with developing a plan to guide future land use and management of the valley. A FOUR STEP STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT AUDIT Public Expectations A first step in the planning process involved assessing public perceptions and attitudes toward the refuge and recreation area. This effort focused on three objectives. First, that the two lead agencies planning the refuge and recreation area were acting within their proper powers and responsibilities. Management Performance and Trends The third element in developing effective strategy is an assessment about past performance, the current situation and trends affecting management. The abundance of 404 considerable support from citizen groups on the river. wildlife in the valley has been noted as far back as the 1830's. Inventories and surveys have recorded approximately 50 species of mammals and 100 species of birds resident to the valley. Approximately 275 species have been counted during migration, twenty-two of them waterfowl. Aerial surveys have counted up to 40,000 waterfowl during fall migration and twenty-six whitetail deer per square mile. The planning process surfaced four threats which could adversely affect the refuge/ recreation area. They were declining water quality from the springs and seeps which feed the lakes and fens of the area. Exclusion of federal and state lands from regional land use policy, resulting in an inability to enforce detrimental changes in local planning and zoning. The nonconforming nature of the state's lands in the valley with existing state recreation land classification which could potentially lead to an inability to fund itate projects, and finally, the complex and nontraditional character of t~e project which often lead to a resistence to change from traditional administrative policies. The recreational significance of the valley dates back to the early 1900's and the establishment of some of the gun clubs in the valley. The 1960's saw the establishment of 3,200 acre Fort Snelling State Park, the 72 mile 9,000 acre Minnesota Valley Trail and the designation of the river as a state canoe and boating route. Considerable acquisition took place in the valley during this time for state facilities, as well as local and regional parks and open space. Combined with protective regulatory programs such as shoreland zoning, the state protected waters program, and the federal 404 program, approximately sixty percent of the refuge and recreation area involved at least some public interest. The recreational opportunities of the valley occur in what could be called natural urban and rural settings. An extremely high number of scenic, natural, and historic attributes combined with extensive areas of natural vegetation and screening from the river bluffs provide both real and perceived opportunities for feelings of remoteness. The planning process was able to draw on four stengths to deal with these situations. First the planning process was able to tap and utilize the vision, intuition and networking abilities of the state and federal managers. Their ability to soften the internal resistence to the complexities of the project and gain needed contacts with and perspectives on the local political environment, and land use situation was essential. Second, the involvement of federal, state and local governments .in the planning process provided a more complete picture of the potential techniques and programs which could be used to complete the project, such as the metropolitan surface water management program, and the state · critical area program. Third, the strong citizen support provided a resource that if organized could support the project through political initiative. Fourth, local, state and federal managers were, for the most part, able to consider and adopt techniques such as performance zoning and transfer of development rights, to provide opportunities for both the conservation of riparian lands and economic development. The trends for both wildlife and recreation were characterized by an increasing need for opportunity combined with an. increasing pressure to utilize lands for commercial purposes. This general trend is expected to continue. Strategic Capability An assessment of the strategic management situation of the valley involved identifying favorable and unfavorable situations affecting the project and the capability of the management organization to deal with them. Countering these capabilities were two serious weaknesses. First, the lack of federal funding to complete acquisition of the refuge and second, the absence of a formal policy on the state and regional levels that recognizes the significance of the refuge/recreation area so that coordination is required between local, state and federal activities. The planning process surfaced five opportunities to establish, and enhance the management of the refuge/recreation area. First, was the planning process. By creating a planning team with federal, state and local involvement, the potential for cooperation, and coordination, was maximized. Second, the local units of government involved in the project were in the process of completing comprehensive plans of their own on \oThich future zoning and development decisions would be made. Third, the boundaries of the refuge/recreation area had excluded the major commercial and industrial areas of the valley, which highlighted the opportunity and the need to cluster those uses. Fourth, the valley is dominated by the Minnesota river. The natural floodplain and wetlands that occur there provide a necessary buffer and storage basin for flooding. Fifth, the project enjoyed ENVIRONMENT AND STRATEGY Strategic management involves relating the management organization to its external forces. Broadly speaking, external forces create the environment within which missions will be pursued, change will occur, and choice must be made. The external forces may then be viewed in terms of the physical, social and managerial settings. From a strategic perspective, the crux of an environmental analysis is to determine what external opportunities and constraints face management goals. Strategy 405 formulation addresses a set of dimensions which attempt to coordinate and form a logical fjt between those goals and the external forces. The essence of successful strategy is to find the right opportunity and utilize the strengths available to the organization to pursue it (Steiner, 1979) . CONCLUSION The underlying premise of this paper is that strategic planning is a management tool which should be undertaken either implicitly or explicitly by agencies and individuals involved in riparian resource management. Too frequently, with the daily need for problem solving, managers are compelled to focus soley on the operational level. The need is to keep the crises of yesterday and today in perspective so that the opportunities of tomorrow can be recognized. If managers are not constantly looking for new opportunities and favorable situations affecting their ' mission, there can be no progress toward "reconciling conflicting uses"·, or positively managing riparian lands. Therefore, a regular strategic planning session could keep the forward momentum going. The basic strategy in place in the MinnesotR Valley is a joint venture between federal, state and local governments. The coordination and cooperation achieved during the planning process provide for flexibility and innovation in pursuing goals, permits informality and initiative on the part of the agencies involved, and allows for rapid response to problems and changes in priorities. The method advocated in the plan for linking the different agencies is a tier system of plans and zoning ordinances at the municipal, county and regional levels. These local plans are to be consistent with the basic goals and standards for performance detailed in the plan for the valley. To date, all of the local units of government have recognized the refuge and recreation area in their comprehensive plans and approximately half have adopted some type of protective zoning in the form of shoreland or sensitive land zoning. The strategy in effect on the Minnesota Valley National Wildlife Refuge and Recreation Area is currently being reviewed as part of the Metroplitan River Corridors Study. The study's purpose is to recommend policies and actions to optimize the recreational, fish and wildlife, historic, natural, scientific, scenic and cultural values of the Mississippi, Minnesota, and St. Croix rivers within the Minneapolis and St. Paul metropolitan area (P.L.96-607). Research for the study implies that the current strategy for the Minnesota Valley does not offer long term insurance for protecting the resources of the valley. While the study will not be complete until June, 1985, the data and capability does exist to address the four strategic elements discussed earlier and effectively mediate the institutional and policy differences that exist in the management environment of the valley. This is essential if the project is to have a future. This arrangement does have it's strategic pitfalls, however. The success of the management system is critically dependent on the leadership of a few key managers. Line staff must be flexible and willing to assume different responsibilities and address different sorts of problems than those found on traditional refuges and recreation resources. Authority relationships are constantly changing, leading to problems of dual command and functional coordination, and finally, the flexibility and informality provided by a joint venture can lead to too much independence by the involved agencies and a breakdown in interagency coordination. Strategic planning, however, is not deciding what to do in the future, it is deciding what to do now in order to deal with the future. In view of this, planning can not be the responsibility of some unit tucked away in a dark corner at headquarters. Too often planning is assigned to an individual 't<Jho is "in charge of planning", what ever that means. Unfortunately the designee is usually a staff member who "coordinates" or "leads" the planning effort. Planning is a process, not an effort. It can not be effective if done by staff invulnerable to the risk of failure. The onus to plan lies with each unit manager, the line person responsible for driving an activity forward. The planning function is only responsible for giving form and shape to managements objectives. The strategic management effort of the Minnesota Valley has encountered all of these pitfalls a~d has coped with them through vigilance, a commitment to transforming the social and cultural setting of land management. The primary tools have been "jawboning", networking and an underlying philosophy which focuses on the production of opportunities and the performance of natural systems and settings. The management guidelines have been in the form of performance standards. By establishing thresholds and parameters for natural and recreation systems, the opportunity exists to develop policies that are empirically based, and defendable in terms of the health, safety and welfare of the public. The result places managers on the offensive and able to respond to changes in the strategic environment. Examples in use in the Minnesota Valley are the recreation opportunity spectrum and performance zoning for sensitive lands such as wetlands and floodplains (Brown, Driver and McConnell,l978, Thurow, Toner and Erly,1975). This is not to say that there isn't a need for planners in an organization. The task of giving expression to managements opportunities, and how they are going to be tackled is not a static process. It is an essential element in the iterative process which brings out the inconsistencies of thinking, and pulls together the different perspectives and contributions of 406 Ginn, Richard H.and James H. Burbank 1978. Protecting Riparian Ecosystems from Competing Urban Pressures-The Swan Creek Experience. p.207-215. In Strategies for Protection and Management of Floodplain Wetlands and Other Riparian Ecosystems: Proceedings of the National Symposium. [Pine Mountian, Georgia, Dec. 11-13,1978]. King, David A. 1972. Towards More Effecti.ve Natural Resource Planning. p.260-267. In Transactions of the Thirty-seventh North American Wildlife and Natural Resource Conference. [March 12-15,1972] Wildlife Management Institute, Washington D.C. Steiner, George A. 1979. Strategic Planning: What Every Manager Must Know. 338p. Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., New York, N.Y. Thurow, Charles, William Toner and Duncan Erly 1975. Performance Controls for Sensitive Lands. The Planning Advisory Service, 156p. American Society of Planning Officials. Chica2o. T11 U.S. Laws, Statutes, etc. 1976. The Minnesota Valley National Wildlife Refuge Act of 1976. An act providing for a national wildlife refuge in the Minnesota river valley. Public Law 94-466. In it's United States stautes at large. 1976. 90 Stat. 1992 (16 USC 668) U.S. Gov. Print. Off., Washington D.C. U.S. Laws, Statutes, etc. 1980. National Park System Amendments of 1980. An act providing for a committee to study the the preservation, enhancement, protection, and use of the designated recreation, park, open space and historic sites along the Mississippi, Minnesota and St.Croix rivers within the Twin Cities metropolitan area. Title IX, Public Law 96-607. In it's United States statutes at large. 1980. 96 Stat. 1520 U.S. Gov. Print. Off., Washington D.C. the disciplines reporting to the unit manager. This is needed so that a coherent view of the mission and the path being followed is shared by the management team. I started this paper with the statement that th~ way plans are done could stand improvement. I conclude by highlighting the need for management to understand the different levels of planning, their relationship and their place of order. Finally, managers should decide to plan strategically, because the plan is the decision which directs the way a mission will be pursued and provides a reference point to judge what's happening in the total managerial environment. If you don't have a reference point you can't make evaluations and judgements on progress or a change in the course of management. On the other hand, if you don't care where you are going, any road will get you there. LITERATURE CITED Bailey, James A. 1982. Implications of "Muddling Through" for Wildlife Management. Wildlife Society Bulletin 10(4):363-369. Brown, P.J., B.L. Driver and C. McConnell 1978. The Opportunity Spectrum Concept and Behavioral Information in Outdoor Recreation Resource Supply Inventories: Background and Application. p.73-84. In Integrated Inventories of Renewable -Natural Resources: Proceedings of the Workshop. [Tucson, Ariz., Jan.8-12,1978] USDA Forest Service General Technical Report RM-55, 482p. Rocky Mountian Forest and Range Experiment Station, Ft. Collins, Colo. 407