CAN ANNUAL RANGELANDS CONVERTED MAINTAINED AS PERENNIAL GRASSLANDS THROUGH

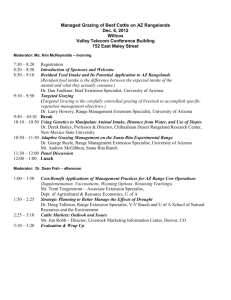

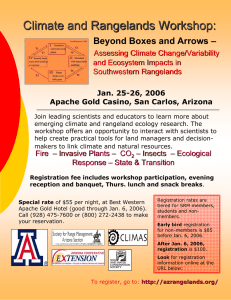

advertisement

This file was created by scanning the printed publication.

Errors identified by the software have been corrected;

however, some errors may remain.

CAN ANNUAL RANGELANDS BE

CONVERTED AND MAINTAINED AS

PERENNIAL GRASSLANDS THROUGH

GRAZING MANAGEMENT?

Kenneth D. Sanders

ABSTRACT

Essentially three options are available for the management

of annual rangelands: (a) management as an annual rangeland; (b) conversion to a perennial rangeland through grazing management; and (c) conversion to a perennial rangeland by reseeding. The second option is most desirable-if

it is feasible. Evidence suggests that annual rangelands in

higher precipitation zones can be converted through grazing management, providing there are suffzcient perennial

plants present as a seed source. However, in the drier annual rangelands, the preponderant evidence indicates little

chance of conversion through grazing management.

INTRODUCTION

Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) and medusahead (Taeniatherum asperum ) dominate several million acres of rangelands in southern Idaho and adjacent States. There are

also millions of acres of annual grasslands in California.

Much of this area has been dominated by annuals most

of this century. Many rangeland management plans in

effect in Idaho have the objective of improving low-seral

range (cheatgrass) to high-sera! bluebunch wheatgrass

<Elytrigia spicata) or Stipa sp., etc., in a few cycles of a

grazing system, with, of course, a 30, 50, or 70 percent reduction in livestock numbers. Is this a realistic objective?

SEVERAL VIEWS

In describing the valley grasslands of California, Heady

(1977) stated that ecologists should recognize that species

labeled as "introduced" and "alien" cannot be removed and

perhaps not even reduced from their present state under

any known ra ngeland management practice. Laycock

(1991) discussed the concepts of stable states and thresholds of range condition on North American rangelands. Although not new concepts, they have only recently received

much attention in U.S. range literature and discussions.

Laycock points out that it is important for range managers

to recognize that multiple steady states exist for many vegetation types, such as cheatgrass rangelands in southern

Idaho. Under our current range condition model, many assume that a reduction in grazing pressure and improved

P~per presented at the Symposium on Ecology, Management, and RestoratiOn of Intermountain Annual Rangelands, Boise, 10, May 18-22, 1992.

K.enneth D. Sanders is Professor, Department of Range Resources, University of Idaho, P.O. Box 1827, Twin Falls, ID 83303·1827.

412

grazing management will result in range improvement.

However, in a stable lower successional state, range condition normally will not respond to change in grazing or

even to no grazing. Friedel (1991) suggested that once a

threshold is crossed to a more degraded state, improvement cannot be obtained on a practical time scale without

a much greater intervention or management effort than

simple grazing control.

Using the California annual grasslands as one example,

Johnson and Mayeux (1992) offer the viewpoint that no

special significance should be attributed to the label "native" when looking at ecological plant performance. They

suggest the evidence they present is "contrary to a common

assumption that the dominance of undesirable plants on

rangelands always serves as evidence of overgrazing by

livestock and that an elimination or reduction in grazing

pressure will result in the reduction of undesirable species

and a return to 'climax' species composition."

In the higher precipitation zones (14 inches plus) in

the Intermountain Region, there is some evidence that

cheatgrass rangelands can be reclaimed by native perennial grasses, providing there is a seed source. Even in

this precipitation zone, my personal observation has been

that the conversion seldom occurs without some means of

reducing the annual grass competition (herbicides, fire,

heavy spring grazing). There is little evidence that annual

rangelands below 12 inches precipitation can be successfully converted to perennial grasslands through grazing

management alone. Laycock (1991) and Heady (1977) both

point out that there is no known grazing system that will

accomplish this feat alone. In fact, failure is more the rule

than success in converting cheatgrass rangelands in southern Idaho to perennial grasses, even when burned and

seeded to competitive grasses such as crested wheatgrass

(Agropyron desertorum, A cristatum).

Why is it so difficult to convert annual grasslands to

perennial grasslands? Laycock (1991) gave the following

reasons for "suspended stages" such as cheatgrass rangeland: dominance by a highly competitive species or lifeform; long generation times of the dominant species; lack

of seed or seed source; specific physiological requirements

that limit seedling establishment except at infrequent intervals; climatic changes; restriction of natural fires or increase in frequency of fires; and others.

In his presentation on medusahead, Dr. Min Hironaka

stated that squirreltail grass (Sitanion hystrix) is the only

native perennial grass he knows of that can compete with

medusahead (see Hironaka, these proceedings). Hironaka

and Tisdale (1963) studied the Piemeisel exclosures in

southern Idaho. While they found squirreltail possessed

the ability to convert cheatgrass ranges to a perennial cover,

conversion requires {1) an ample and mobile seed supply of

the perennial species; (2) that the perennial species have

an inherent ability to withstand cheatgrass competition as

a seedling; and (3) that the perennial seedlings be protected

from damage by rabbits as well as livestock. I would add

to that list protection from insects such as grasshoppers.

grazing management alone, such as a rest-rotation grazing

system, if the following conditions are met: (1) an adequate

seed source of the desired perennial(s); (2) no large populations of rabbits, grasshoppers, or Mormon crickets; and

(3) no extended drought. Do not expect the conversion to

occur in just a few years.

Below the 12-inch precipitation zone, either (1) manage

as an annual rangeland and quit worrying about using only

50 percent of the current year's growth; or (2) burn, spray,

or disk in the fall, reseed with Hycrest crested wheatgrass

(don't waste money on anything else) and hope for a wet

spring.

THE OPTIONS

Essentially three options are available for managers of

annual rangelands: (a) management as an annual rangeland; (b) conversion to a perennial rangeland through manipulation of grazing management; and (c) conversion to

a perennial rangeland by reseeding. The first option is

ecologically unacceptable to some and provides a less reliable forage base. The third option may not be economically

feasible and is sociologically unacceptable to some if introduced species are used. Most users and managers of annual

rangelands would opt for conversion to perennial rangelands if ecologically and economically feasible.

The question is-under what condition is it reasonable

to expect to convert an annual grassland to a perennial

grassland in southern Idaho? There is no magic formula

to answer the question, but I will make the following suggestions. First, get as many knowledgeable people together

as you can, including the livestock permittee(s), get out on

the site to be discussed and make a group decision.

In the 14-inch and above precipitation zones, you might

consider trying to convert to a perennial grassland through

REFERENCES

Friedel, M. H. 1991. Range condition assessment and the

concept of thresholds: a viewpoint. Journal of Range

Management. 44(5): 422-426.

Heady, Harold F. 1977. Valley grassland. In: Barbour,

M. E.; Major, J., eds. The terrestrial vegetation of

California. New York: John Wiley and Sons: 491-514.

Hironaka, M.; Tisdale, E. W. 1963. Secondary succession

in annual vegetation in southern Idaho. Ecology. 44(4):

810-812.

Johnson, Hyrum B.; Mayeux, Herman S. 1992. Viewpoint:

a view on species additions and deletions and the balance of nature. Journal of Range Management. 45(4):

322-333.

Laycock, W. A 1991. Stable states and thresholds of range

condition on North American rangelands: a viewpoint.

Journal of Range Management. 45(4): 427-433.

413