O A H :

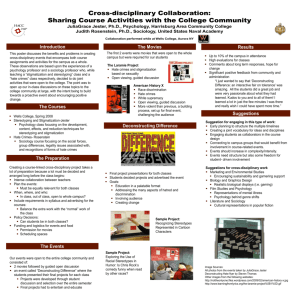

advertisement