Breaking down barriers: Predicting paternal involvement in school

advertisement

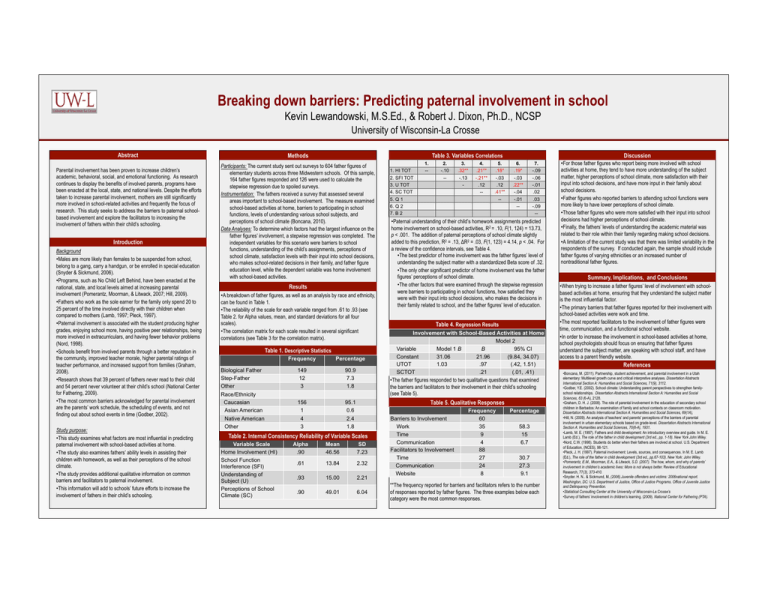

Breaking down barriers: Predicting paternal involvement in school Kevin Lewandowski, M.S.Ed., & Robert J. Dixon, Ph.D., NCSP University of Wisconsin-La Crosse Abstract Parental involvement has been proven to increase children’s academic, behavioral, social, and emotional functioning. As research continues to display the benefits of involved parents, programs have been enacted at the local, state, and national levels. Despite the efforts taken to increase parental involvement, mothers are still significantly more involved in school-related activities and frequently the focus of research. This study seeks to address the barriers to paternal schoolbased involvement and explore the facilitators to increasing the involvement of fathers within their child’s schooling. Introduction Background • Males are more likely than females to be suspended from school, belong to a gang, carry a handgun, or be enrolled in special education (Snyder & Sickmund, 2006). • Programs, such as No Child Left Behind, have been enacted at the national, state, and local levels aimed at increasing parental involvement (Pomerantz, Moorman, & Litwack, 2007; Hill, 2009). • Fathers who work as the sole earner for the family only spend 20 to 25 percent of the time involved directly with their children when compared to mothers (Lamb, 1997; Pleck, 1997). • Paternal involvement is associated with the student producing higher grades, enjoying school more, having positive peer relationships, being more involved in extracurriculars, and having fewer behavior problems (Nord, 1998). • Schools benefit from involved parents through a better reputation in the community, improved teacher morale, higher parental ratings of teacher performance, and increased support from families (Graham, 2008). • Research shows that 39 percent of fathers never read to their child and 54 percent never volunteer at their child’s school (National Center for Fathering, 2009). • The most common barriers acknowledged for parental involvement are the parents’ work schedule, the scheduling of events, and not finding out about school events in time (Godber, 2002). Study purpose: • This study examines what factors are most influential in predicting paternal involvement with school-based activities at home. • The study also examines fathers’ ability levels in assisting their children with homework, as well as their perceptions of the school climate. • The study provides additional qualitative information on common barriers and facilitators to paternal involvement. • This information will add to schools’ future efforts to increase the involvement of fathers in their child’s schooling. Methods Table 3. Variables Correlations Participants: The current study sent out surveys to 604 father figures of elementary students across three Midwestern schools. Of this sample, 164 father figures responded and 126 were used to calculate the stepwise regression due to spoiled surveys. Instrumentation: The fathers received a survey that assessed several areas important to school-based involvement. The measure examined school-based activities at home, barriers to participating in school functions, levels of understanding various school subjects, and perceptions of school climate (Boncana, 2010). Data Analyses: To determine which factors had the largest influence on the father figures’ involvement, a stepwise regression was completed. The independent variables for this scenario were barriers to school functions, understanding of the child’s assignments, perceptions of school climate, satisfaction levels with their input into school decisions, who makes school-related decisions in their family, and father figure education level, while the dependent variable was home involvement with school-based activities. Results • A breakdown of father figures, as well as an analysis by race and ethnicity, can be found in Table 1. • The reliability of the scale for each variable ranged from .61 to .93 (see Table 2. for Alpha values, mean, and standard deviations for all four scales). • The correlation matrix for each scale resulted in several significant correlations (see Table 3 for the correlation matrix). Table 1. Descriptive Statistics Biological Father Step-Father Other Race/Ethnicity Caucasian Asian American Native American Other Frequency Percentage 149 12 3 90.9 7.3 1.8 156 1 4 3 95.1 0.6 2.4 1.8 2. -.10 -- 3. .32** -.13 - 4. .21** -.21** .12 -- 5. .18* -.03 .12 .41** -- Discussion 6. .19* -.03 .22** -.04 -.01 -- 7. -.09 -.06 -.01 .02 .03 -.09 -- • Paternal understanding of their child’s homework assignments predicted home involvement on school-based activities, R2 = .10, F(1, 124) = 13.73, p < .001. The addition of paternal perceptions of school climate slightly added to this prediction, R2 = .13, ΔR2 = .03, F(1, 123) = 4.14, p < .04. For a review of the confidence intervals, see Table 4. • The best predictor of home involvement was the father figures’ level of understanding the subject matter with a standardized Beta score of .32. • The only other significant predictor of home involvement was the father figures’ perceptions of school climate. • The other factors that were examined through the stepwise regression were barriers to participating in school functions, how satisfied they were with their input into school decisions, who makes the decisions in their family related to school, and the father figures’ level of education. Table 4. Regression Results Involvement with School-Based Activities at Home Model 2 Variable Model 1 B B 95% CI Constant 31.06 21.96 (9.84, 34.07) UTOT 1.03 .97 (.42, 1.51) SCTOT .21 (.01, .41) • The father figures responded to two qualitative questions that examined the barriers and facilitators to their involvement in their child’s schooling (see Table 5). Table 5. Qualitative Responses Table 2. Internal Consistency Reliability of Variable Scales Variable Scale Home Involvement (HI) School Function Interference (SFI) Understanding of Subject (U) Perceptions of School Climate (SC) 1. HI TOT 2. SFI TOT 3. U TOT 4. SC TOT 5. Q 1 6. Q 2 7. B 2 1. -- Alpha .90 Mean 46.56 SD 7.23 .61 13.84 2.32 .93 15.00 2.21 .90 49.01 6.04 Barriers to Involvement Work Time Communication Facilitators to Involvement Time Communication Website Frequency 60 35 9 4 88 27 24 8 Percentage 58.3 15 6.7 30.7 27.3 9.1 **The frequency reported for barriers and facilitators refers to the number of responses reported by father figures. The three examples below each category were the most common responses. • For those father figures who report being more involved with school activities at home, they tend to have more understanding of the subject matter, higher perceptions of school climate, more satisfaction with their input into school decisions, and have more input in their family about school decisions. • Father figures who reported barriers to attending school functions were more likely to have lower perceptions of school climate. • Those father figures who were more satisfied with their input into school decisions had higher perceptions of school climate. • Finally, the fathers’ levels of understanding the academic material was related to their role within their family regarding making school decisions. • A limitation of the current study was that there was limited variability in the respondents of the survey. If conducted again, the sample should include father figures of varying ethnicities or an increased number of nontraditional father figures. Summary, Implications, and Conclusions • When trying to increase a father figures’ level of involvement with schoolbased activities at home, ensuring that they understand the subject matter is the most influential factor. • The primary barriers that father figures reported for their involvement with school-based activities were work and time. • The most reported facilitators to the involvement of father figures were time, communication, and a functional school website. • In order to increase the involvement in school-based activities at home, school psychologists should focus on ensuring that father figures understand the subject matter, are speaking with school staff, and have access to a parent friendly website. References • Boncana, M. (2011). Partnership, student achievement, and parental involvement in a Utah elementary: Multilevel growth curve and critical interpretive analyses. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 71(9), 3112. • Godber, Y.E. (2002). School climate: Understanding parent perspectives to strengthen familyschool relationships. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 63 (6-A), 2128. • Graham, D. H. J. (2008). The role of parental involvement in the education of secondary school children in Barbados: An examination of family and school contexts on classroom motivation. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 69(1A), • Hill, N. (2009). An analysis of teachers' and parents' perceptions of the barriers of parental involvement in urban elementary schools based on grade-level. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 70(6-A), 1931. • Lamb, M. E. (1997). Fathers and child development: An introductory overview and guide. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (3rd ed., pp. 1-18). New York John Wiley. • Nord, C.W. (1998). Students do better when their fathers are involved at school. U.S. Department of Education, (NCES), 98-121. • Pleck, J. H. (1997). Paternal involvement: Levels, sources, and consequences. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (3rd ed., pp.67-103). New York: John Wiley. • Pomerantz, E.M., Moorman, E.A., & Litwack, S.D. (2007). The how, whom, and why of parents’ involvement in children’s academic lives: More is not always better. Review of Educational Research, 77(3), 373-410. • Snyder. H. N.. & Sickmund, M, (2006).Juvenile offenders and victims: 2006national report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. • Statistical Consulting Center at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse’s • Survey of fathers’ involvement in children’s learning. (2009). National Center for Fathering (PTA).