Guide for Department Chairs Knox College Galesburg, Illinois

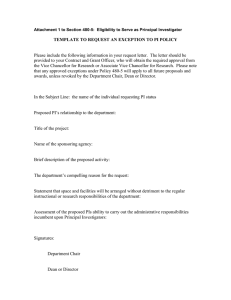

advertisement