D The Three Block Fellowship

advertisement

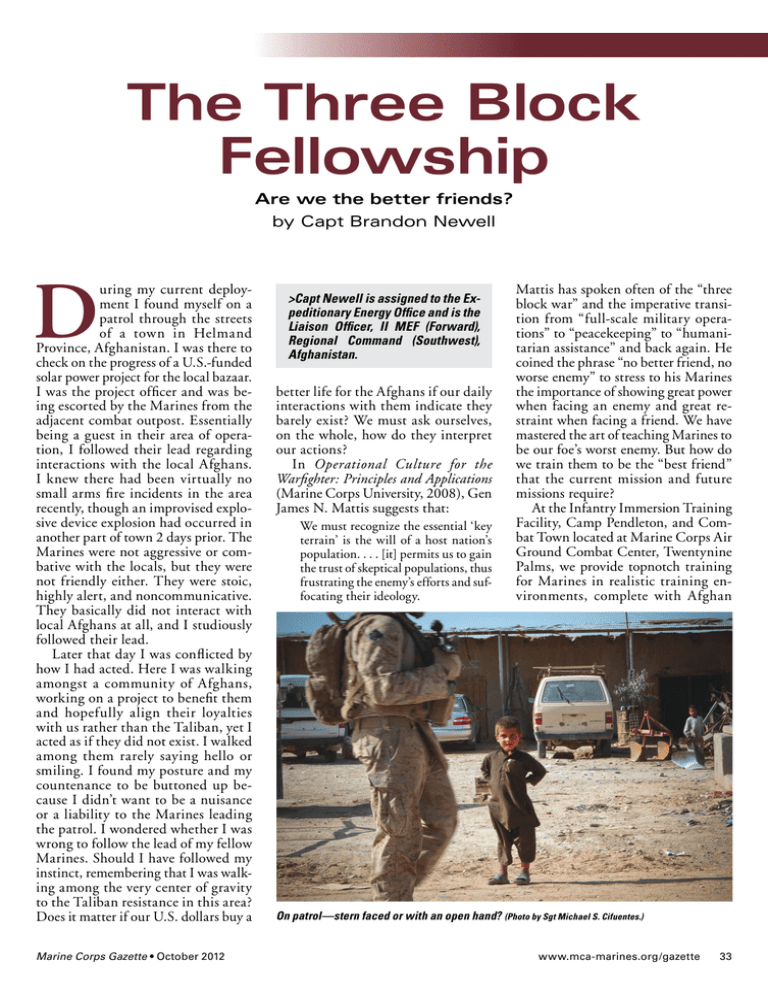

The Three Block Fellowship Are we the better friends? by Capt Brandon Newell D uring my current deployment I found myself on a patrol through the streets of a town in Helmand Province, Afghanistan. I was there to check on the progress of a U.S.-funded solar power project for the local bazaar. I was the project officer and was being escorted by the Marines from the adjacent combat outpost. Essentially being a guest in their area of operation, I followed their lead regarding interactions with the local Afghans. I knew there had been virtually no small arms fire incidents in the area recently, though an improvised explosive device explosion had occurred in another part of town 2 days prior. The Marines were not aggressive or combative with the locals, but they were not friendly either. They were stoic, highly alert, and noncommunicative. They basically did not interact with local Afghans at all, and I studiously followed their lead. Later that day I was conflicted by how I had acted. Here I was walking amongst a community of Afghans, working on a project to benefit them and hopefully align their loyalties with us rather than the Taliban, yet I acted as if they did not exist. I walked among them rarely saying hello or smiling. I found my posture and my countenance to be buttoned up because I didn’t want to be a nuisance or a liability to the Marines leading the patrol. I wondered whether I was wrong to follow the lead of my fellow Marines. Should I have followed my instinct, remembering that I was walking among the very center of gravity to the Taliban resistance in this area? Does it matter if our U.S. dollars buy a Marine Corps Gazette • October 2012 >Capt Newell is assigned to the Expeditionary Energy Office and is the Liaison Officer, II MEF (Forward), Regional Command (Southwest), Afghanistan. better life for the Afghans if our daily interactions with them indicate they barely exist? We must ask ourselves, on the whole, how do they interpret our actions? In Operational Culture for the Warfighter: Principles and Applications (Marine Corps University, 2008), Gen James N. Mattis suggests that: We must recognize the essential ‘key terrain’ is the will of a host nation’s population. . . . [it] permits us to gain the trust of skeptical populations, thus frustrating the enemy’s efforts and suffocating their ideology. Mattis has spoken often of the “three block war” and the imperative transition from “full-scale military operations” to “peacekeeping” to “humanitarian assistance” and back again. He coined the phrase “no better friend, no worse enemy” to stress to his Marines the importance of showing great power when facing an enemy and great restraint when facing a friend. We have mastered the art of teaching Marines to be our foe’s worst enemy. But how do we train them to be the “best friend” that the current mission and future missions require? At the Infantry Immersion Training Facility, Camp Pendleton, and Combat Town located at Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center, Twentynine Palms, we provide topnotch training for Marines in realistic training environments, complete with Afghan On patrol—stern faced or with an open hand? (Photo by Sgt Michael S. Cifuentes.) www.mca-marines.org/gazette 33 Ideas & Issues (Commentary) We should be interpreting our actions through their culture and experiences. (Photo by Sgt Logan Pierce.) role-players and simulated improvised explosive devices. I marvel at the improvements made in training since I began my career 10 years ago. But is it enough, and is it sustainable? While the Marines will be better prepared for their deployment surroundings, are they effectively prepared to show Afghans we are the better friends? As for future missions around the world, do our training methods translate into being a better friend to cultures we will encounter? We have yet to effectively train our Marines on how to become the better friend. To do so we need to genuinely understand who we are trying to befriend. This is not pacifism, it is maneuver warfare. For the local populace is the center of gravity in this fight against ideological nonstate actors. Now on the surface we believe we are doing well. We patrol their streets, which to us represents security. We spend money 34 www.mca-marines.org/gazette on development, which to us means prosperity. We kill those who wrongly subjugate civilians, which to us means hope for their future. Now read those three statements again. Two words shed light on our shortcoming in this area: to us. We interpret our actions through our culture and our experiences, expecting locals to see it in the same light. This expectation is not only ignorant but dangerously shortsighted. We have taken men and women from Ohio, California, New York, and Louisiana. We have trained them and built them into Marines, instilling our core values. We have trained them in the basics of infantry and then trained them in the particulars of their MOSs. All of this has molded them into exceptional warfighters. Now to prepare them for their upcoming deployments to Afghanistan we have sent them through the Infantry Immersion Training Center and Combat Town. One could argue that today’s Marines are better prepared for their upcoming deployments than any of their predecessors in the last 236 years. But do they have the ability to readily operate in a culture completely foreign to our own? The majority of Americans don’t know what it feels like to worry that their children will starve. Most of us don’t know how it feels to watch loved ones die of acquired immune deficiency syndrome. We don’t live in fear of antagonistic police or a corrupt local government. We haven’t experienced a life in which the only guaranteed protection of our family lies in our own hands. The places we deploy to most often know only these truth conditions. These cultures are in many ways the complete opposite of our own. Yet the first time we truly expose our Marines to these alien environments is under the context of combat. This leads them to err on the side of security and firepower, Marine Corps Gazette • October 2012 because we naturally gravitate toward the actions we are most often taught. In Baghdad (2003), just 3 days after the statue of Saddam was famously yanked down, I found myself 100 yards from that site providing communications for the civil-military operations center. After weeks of racing through southern Iraq, expecting to be hit with chemical weapons or engaged by Saddam’s forces, I was in the midst of a fullscale civil-military operation focused on restoring the country’s infrastructure. Each day Iraqis would line up 100 deep to offer their services to restore the infrastructure. Twice daily an organized mob formed on the street, collectively chanting for an hour. Some days the chants were anti-Saddam; other days they were anti-United States. While my fellow Marines were spread throughout Baghdad trying to restore order, their operations falling somewhere between full-scale combat operations and peacekeeping, I had to quickly transition my mindset to humanitarian aid. I learned then and there that maintaining a comfortable barrier of security was counterproductive to the civil-military mission. I had no choice but to let my guard down and interact with local Iraqis, simply as people and not as threats. I had to use my intuition to determine if someone was a friend or a foe. Later in my career I deployed to Haiti following the January 2010 earthquake. I was the lone uniformed member of a six-member team tasked with facilitating civil-military coordination between U.S. Government organizations and the nongovernmental organization community. Before leaving the United States I watched with the rest of America as clip after clip on the news showed “machetewielding Haitians causing anarchy.” But what I saw in Port-au-Prince was very different. What I saw was people trying to figure out a path forward from the devastation. I decided to change out of my uniform so that I could move freely around the city. I jumped in crowded local tabtabs, traveling to the other side of the city in order to check out health clinics that potentially needed communications infrastructure. I walked crowded Marine Corps Gazette • October 2012 streets full of crumbled buildings and homeless civilians. I had no weapon. My only security was my intuition and judgment. I quickly realized that sensationalized stories from the media were not representative of what was happening. The Haitian people were gracious, hopeful, and grateful for the international assistance. I could better facilitate interactions with Haitians and move throughout the city out of uniform and on my own. When I found myself among Marines, however, I noticed a stark contrast in behavior. They wielded their weapons as though they were patrolling the streets of Fallujah, not Port-au-Prince. Their facial expressions and posture intended to intimidate, not support. Who could blame them? They were the finest warfighters in the world, being trained and tested in combat in Iraq and Afghanistan. However, I know their actions were somewhat counterproductive to their mission. Their mission was not just that of providing security. Their mission was to provide assistance to our friends. I learned from my interactions with Haitians that our military’s actions led some to question our motives and create rumors of an invasion. We know this is nonsense. But what does it matter how we interpret our actions? The key to our mission success is how the host nation actually interprets our actions, not how we intend for them to do so. In It Happened on the Way to War (Bloomsbury USA, 2011) by Rye Barcott and The Heart and the Fist (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2011) by Eric Greitens, the authors talk about their experiences doing humanitarian work prior to their military service. Barcott spent a substantial amount of time in the largest slum in Kenya, Kibera, and started a nongovernmental organization himself before his commissioning in the Marine Corps. Greitens did humanitarian work in Rwanda, Croatia, and Bolivia before being commissioned in the Navy and becoming a SEAL. As I read their stories I saw in both of their perspectives one that mirrored my own. I saw that their experiences gave them the ability to see the humanity of individuals in a culture foreign to their own. I saw that they did not err on the side of security and firepower because they were better prepared to distinguish friend from foe and engage with the friend in a way that promoted trust. They understood how to listen and communicate with individuals of different cultures. These men and their stories revealed to me a training strategy that could address the gap in our cultural limitations. I’ll call it the three block fellowship. The three block fellowship concept is very simple. We take young officers, grow their hair out, put them in civilian clothing, and send them for 3 months to work with humanitarian organizations in the slums of the world. Then we bring them back to whatever Marine Corps path they were on. There is no special MOS, no special duty or assignment. These officers will have an opportunity to live and serve, day in and day out, among those in true need and learn to earn their respect and trust. The exposure will give them better instincts to distinguish friend from foe in foreign lands, and a better understanding of the motivations that shape the lives of people whom they will need to befriend in future operations. The experience would serve them well in combat and prepare them for the three block war. Leadership sets the tone. Junior officers who receive this cultural immersion experience will be equipped with the intuition required to set an appropriate tone for their Marines wherever they may go. This is a broad strategy that prepares Marines for deployments to any part of the world. If the tenets of maneuver warfare are to be believed, we have to concede that combat firepower alone will not bring victory. Innate cultural intuition is critical to winning the will of the host-nation’s people and defeating the enemy’s center of gravity. The three block fellowship strategy will bear fruit no matter where Marines are called to be the best friends or worst enemies that Gen Mattis described. www.mca-marines.org/gazette 35