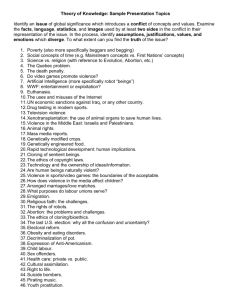

J S P

advertisement