1. Introduction

advertisement

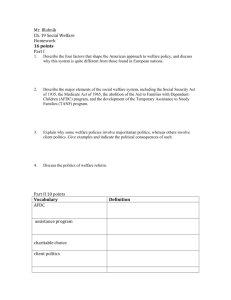

TANF, SNAP, and Substance Use Joshua Price 1. Introduction As long as there has been public assistance, people have decided who deserves to receive benefits. Those considered undeserving in America has included men, women, Hispanics, and African Americans (Katz 2013). Since 1996, substance users have received more attention as the undeserving with a public perception that the majority of aid recipients are also drug addicts (see Califano 1995). This has increased States’ attempts to require drug testing for aid applicants and recipients. It has been almost 20 years since the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 overhauled the “welfare” system. Research leading up to this reform sought to identify characteristics of program participants and extended program receipt. Most of the research after the reform sought to determine what lead to the sharp decline in caseloads or determine how multiple employment barriers affect an individual’s ability to end program participation. Little research has focused specifically on how substance use affect program participation decisions, a more policy relevant question. The goal of this study is to determine the causal relationship between substance use and public assistance eligibility and participation decisions. Specifically, I consider alcohol and marijuana use as determinants of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), henceforth referred to collectively as “public assistance.” This study contributes to the literature by establishing how alcohol and marijuana use affect public assistance eligibility and participation decisions in the post-reform era. This is done through use of nationally representative data of young females who are unlikely to have participated in 1 TANF’s predecessor as an adult. This study includes SNAP eligibility and participation decisions in its analysis. While program restrictions related to substance use include both TANF and SNAP, research has focused on TANF. This study improves upon previous research by accounting for unobserved heterogeneity using a discrete factor approximation model. While there have been some attempts to determine the relationship between substance use and public assistance, those studies fail to account for endogeneity. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the history of public assistance and empirical literature related to substance use and public assistance. Section 3 presents the conceptual framework for how substance use influences public assistance eligibility, entry, and exit. Section 4 discusses data sources, the sample, and provides descriptive statistics. The estimation strategy is presented in Section 5, followed by conclusions in Section 6. 2. Background 2.1. History What many people call “welfare” is the program named Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and what many still call “food stamps” is now known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). These two programs are not new in the U.S. In fact, the history of public assistance can be traced back to the colonial period. Thus, a complete history of public assistance in the U.S. would require its own book (see Katz 1996; Trattner 1998; Stern and Axinn 2011). This section is divided into four subsections. The first subsection discusses programs created as part of the Second New Deal, which refers to the second round of legislative efforts by the Roosevelt administration to combat the Great Depression occurring between 1935 and 1938. The second subsection discusses program changes occurring between the 1960s and the 1990s. The third subsection discusses the enactment of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, commonly referred to as welfare reform. I conclude with a discussion of 2 recent policy changes relevant to public assistance, in particular efforts to impose drug testing requirements. 2.1.1. The Second New Deal The current programs, TANF and SNAP, owe their existence to predecessors created as part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal program. Aid to Dependent Children, TANF’s predecessor, and the Food Stamp Plan, SNAP’s predecessor, were created as key components of the Second New Deal. These programs were created in reaction to the Great Depression as an attempt to create a social safety net. The Social Security Act of 1935 established the program called Aid to Dependent Children (ADC; Public Law 74-271 1935). ADC was a grant program initially designed to cover one-third of mothers’ pensions costs. State participation in ADC was voluntary and eight states – Connecticut, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Mississippi, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas – and the territory of Alaska had no ADC program in 1939 (Coll 1995, p. 104; Gordon and Batlan 2011). ADC remained largely unchanged at the national level until the 1960s. In 1962, ADC was renamed Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). Henceforth, AFDC will be used to refer to both names (ADC and AFDC). The first Food Stamp program, called the Food Stamp Plan, started in 1939. The purpose of this program was to formalize the food distribution begun in 1933 under the Agricultural Adjustment Act (Public Law 73-10 1933). Low-income individuals could purchase orange food stamps and receive blue bonus stamps usable to purchase foods identified as surplus by the Secretary of Agriculture. Orange stamps could be used to purchase food and select household items, but these stamps could not be used to purchase alcohol, tobacco, or foods eaten at stores (“The History of SNAP | Snap To Health” accessed 2015). Blue stamps were restricted to surplus items designated in grocery stores. At the time, the ratio of orange stamps to blue stamps was two-to-one 3 such that for every $1 in orange stamps, program participants would receive $0.50 of blue stamps. The use of both types of stamps was restricted to specific items. While this program ended in 1943, it was restored in the 1964. 2.1.2. Expansion, Contraction, and Waivers (1960s to 1990s) In the beginning, the purpose of AFDC was to provide assistance. By the 1960s, the views of AFDC had shifted to providing assistance while promoting work. This was largely due to changes in the workforce composition, with women becoming a larger proportion. This lead to policy changes in 1967 which “included both ‘carrots’ and ‘sticks’ to promote employment” (Grogger and Karoly 2005, 13). The carrot took the form of a new benefit reduction rate. Prior to 1967, AFDC participants’ earned income decreased their benefits at a one-to-one rate. This new rate disregarded the first $30 of earnings and one-third of the remainder (known as the “$30-and-a-third” rule). The stick took the form of the Work Initiative (WIN) program. “WIN required states to register nonexempt recipients for work-related activities that focused on training and education. But the legislation exempted recipients with children under age six, and they accounted for a substantial fraction of the caseload. As a result, relatively few recipients registered, and ever fewer took part in the programs” (Grogger and Karoly 2005, 14). AFDC benefits were expanded in other ways during the 1960s beginning with the creation of the AFDC-Unemployed Parent program (AFDC-UP) in 1961. This program extended benefits for children in two-parent families where the primary earner is unemployed. Later, several court challenges reached the U.S. Supreme Court. One of the first challenges dealt with states defining “cohabitation” to include casual relationships. Another challenge “found unconstitutional state regulations that required families to live in-state for a certain period of time before becoming AFDC eligible” (Gordon and Batlan 2011). These court challenges led to a relaxing of AFDC eligibility. 4 During the same decade, the Food Stamp Act of 1964 was enacted, restoring and making permanent the food stamp program that had ended in 1943 (Public Law 88-525 1964). Low-income households could purchase food stamps, which held a value greater than their usual expenditure on food. The purpose of this program was to improve nutrition among low-income households. Stamps could be used to purchase food items at approved food stores. Eligible households must meet income limitations, which were determined by the State. While the Nixon administration and Carter administration attempted to reform AFDC to include a balance between better living standards and promoting work, changes would not occur until 1981 with the Reagan administration. The goal of the Reagan administration was to reduce AFDC participation. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1981 was the first change (Public Law 97-35 1981). OBRA increased the benefit reduction rate to 100 percent, as was the case before 1967, after the first four months of work. OBRA reduced AFDC rolls by about 400,000 recipients, but this reduction occurred during a departure from the trend of using incentives and work requirements to promote work (Grogger and Karoly 2005). Financial incentives and work requirements returned with the enactment of the Family Support Act of 1988 (FSA; Public Law 100-485 1988). The Job Opportunities and Basic Skills Training program (JOBS), created by FSA, replaced WIN from 1967. The purpose of JOBS, similar to WIN, was to promote a transition from AFDC to work. One difference between JOBS and WIN was that JOBS only exempted recipients with children under age three (compared to age six with WIN). FSA also required States to provide child care and other services (e.g., medical care) when necessary for participation in JOBS. The Food Stamp program also experienced changes during the 1970s and 1980s. In 1973, States were required to expand the Food Stamp program to individuals in alcohol and drug treatment centers and to disaster victims. The Food Stamp Act of 1977 eliminated the requirement 5 that participants purchase stamps and established uniform national eligibility standards. The Hunger Prevention Act of 1988 was the last change until 1996 (Public Law 100-435 1988). Signed under the Reagan administration, the Hunger Prevention Act aimed to improve child nutrition and food stamp programs. In the early 1990s, states began to take advantage of section 1115 of the Social Security Act. This particular section has existed since 1962, allowing the states the “petition the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) the implement experimental, pilot, or demonstration projects they believed would result in a more effective welfare program” (Grogger and Karoly 2005, 19-20). States taking advantage of these waivers were able to implement AFDC programs that deviated from the legislative requirements. The most common changes made through waivers were changes to the earned income disregard rule, changes to age-related exemptions, changes to work requirements, and inclusion of benefit time limits. 2.1.3. Welfare Reform and Beyond The era of state-level, waiver-based reform led to reform at the national level with the enactment of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA; Public Law 104-193 1996), commonly referred to as the “welfare reform.” The goals of PRWORA are stated well in its preamble that it aimed to: “increase the flexibility of States in operating a program designed to— 1. provide assistance to needy families so that children may be cared for in their own homes or in the homes of relatives; 2. end the dependence of needy parents on government benefits by promoting job preparation, work, and marriage; 6 3. prevent and reduce the incidence of out-of-wedlock pregnancies and establish annual numerical goals for preventing and reducing the incidence of these pregnancies; and 4. encourage the formation and maintenance of two-parent families” (Public Law 104193 1996). With the enactment of PRWORA, the entitlement program AFDC became the transitional program Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF). The key features of TANF were lifetime benefits limits and work requirements. Federal guidelines required recipients to participate in workrelated activity after 24 months of benefits, and recipients could receive benefits for at most 60 months. States were allowed to impose stricter timelines. PRWORA also changed the Food Stamp program. States were required to implement electronic benefit delivery operations, leading to the creation of the Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) system. EBT allows States to issue benefits via a debit card. Retailers must be authorized to accept payment by EBT debit cards. This allowed States to prevent use of Food Stamp benefits for unauthorized items. Small changes were made to the Food Stamp program after 1996. In 2002, eligibility for qualified undocumented aliens and all immigrant children was restored (after being eliminated in 1996). The Food Stamp program became the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in 2008. Monthly benefits were increased as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (Public Law 111-5 2009). 2.1.4. Substance Use and Drug Testing Section 902 of the PRWORA granted States permission to use drug testing for as an eligibility requirement for program participation. Furthermore, the Gramm Amendment (no. 4935) imposed a lifetime ban on TANF and SNAP benefits to individuals with felony convictions for 7 illegal drug possession, use, or distribution. The SNAP lifetime ban applies to convictions after August 22, 1996 (implemented July 1997). The TANF ban applies to convictions after April 1, 2002 (implemented April 2002). States were, however, allowed to modify or revoke the TANF ban. At least 28 States have passed such legislation, and “at least five states have modified the ban to require those convicted of drug felony charges to comply with drug testing requirements as a condition of receiving benefits, including Maine, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin” (“Drug Testing for Welfare Recipients and Public Assistance” 2014). The first State to pass legislation requiring drug testing was Michigan in 1999. Michigan’s law required all applicants to be tested, and 20 percent of recipients were to be randomly tested every six months. Drug testing in Michigan only lasted five weeks before the law was enjoined, testing 258 recipients before being blocked. “Over the short life of this intervention, individuals testing positive for illicit substances remained eligible for [TANF] receipt but were subject to progressive sanctions if they failed to comply with a mandated treatment plan” (Pollack et al. 2002, 26). Of the 258 recipients tested, only 21 tested positive for illicit substance use. Eighteen of the 21 positive results were for marijuana use only (Pollack et al. 2002). This means that about seven percent tested positive for marijuana use, and about 1.2 percent tested positive for illicit, non-marijuana substance use. After the failed experiment in Michigan, drug-testing legislation took a hiatus. It was in 2009 that States began to push for drug testing again. It took another two years before drug testing was enacted. Since 2011, at least 36 States have proposed and 13 States have passed drug testing legislation: Alabama, Arkansas Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Utah (“Drug Testing for Welfare Recipients and Public Assistance” 2014). 8 The only laws that appear to continue are suspicion-based tests, as opposed to suspicionless testing. Suspicion-based testing requires a screening process prior to testing. If the screening process provides reasonable suspicion of drug use, the will be required to take a drug test. If the individual tests positive, then they are ineligible for benefits for six months. The individual has the option to participate in approved rehabilitation and remain eligible for benefits. Georgia’s testing was halted but continued after adding a suspicion-based element to the testing. Florida’s law is currently enjoined due to suspicionless testing. 2.2. Empirical Literature As established in the history section, TANF and SNAP are the names of the current programs. While many of the studies discussed in this section pertain to previous programs, I will use the current names for readability. Thus, TANF and SNAP will henceforth be used in place of AFDC and the Food Stamps program, respectively. 2.2.1. Determinants of TANF/SNAP Entry and Exit In the 1980s, lawmakers were concerned that the structure of TANF incentivized unemployment, childbearing, and begin single (Grogger and Karoly 2005). Such incentives could promote program dependency. These concerns led researchers to investigate who participates in TANF and for how long. Specifically, researchers analyzed which factors influenced entry into and exit out of the program. One of the first studies analyzing TANF exit used data from a single county in California from 1967, 1968, 1970, and 1972 (Wiseman 1977). Analyzing the probability of female-headed family’s TANF exits over three-month periods, less than 20 percent of a month’s caseload left within a year and did not return the following year. Several studies analyzed the Panel Survey of Income Dynamics (PSID; discussed in Section 4). Hutchens (1981) estimated simple transition models of movement into and out of TANF. He 9 found that “other income” (non-TANF and nonemployment income) and potential wage are (negatively) positively related to the probability of (entering) exiting. Using 12 years of data from the PSID, Bane and Ellwood (1983) investigate which characteristics are associated with longer TANF “spells,” a continuous period of TANF participation. While half of TANF spells were completed within two years, 22 percent of leavers return after one year off. Ellwood (1986) updated the previous study by using three more years of data and analyzing TANF re-entry and multiple spells. He finds that over 40 percent of previous TANF participants have multiple spells. After controlling for multiple spells, about 25 percent of anyone who ever participate have 10 or more years of receipt. “The one-quarter of recipients who have very long periods of [TANF] dependence (10 or more years) account for almost 60 percent of those who are found on [TANF] at any point in time. This group presumably consumes at least 60 percent of the program’s resources” (Ellwood 1986, xii). He also finds that “number of children, education, marital status, disability, and work experience are important influences on [TANF] duration” (Ellwood 1986, xii). Early studies used annual data to analyze determinants of TANF entry and exit (e.g., Wiseman 1977; Hutchens 1981; Bane and Ellwood 1983; Plotnick 1983; Ellwood 1986; O’Neill, Bassi, and Wolf 1987). These studies define participation based on surveys that ask if the respondent participated within the past 12 months. Using annual participation data is not ideal because, to use Rebecca Blank’s example “a household could receive [TANF] in January of one year, be off for 22 months, and receive [TANF] in December of the following, and this would be counted as a continuous spell of [TANF]” (Blank 1989, 246). The desire to more accurately analyze the duration of TANF spells led researchers to use monthly data (e.g., Blank 1989; Blank and Ruggles 1996). Blank’s analysis of single TANF spells suggested weak duration dependence in TANF spells (Blank 1989). 10 While TANF studies focused on who participates and for how long, SNAP studies wanted to determine why eligible individuals choose nonparticipation. As implied by the TANF research, individuals who are eligible for a program will participate. This is not always the case. There are a few reasons why an individual may choose nonparticipation, and these reasons are discussed in Section 3. Using data from the PSID, Coe (1983) considered the association between demographic characteristic of a household and nonparticipation in SNAP. Less than half of eligible households participated in SNAP in 1979. Poor information related to eligibility was the biggest barrier to participation (e.g., no knowledge of eligibility requirements or income/assets too high), with more than 40 percent of the eligible nonparticipants believing they were not eligible (Coe 1983). Using data from the 1986 and 1987 panels of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP, discussed more in Section 4), Blank and Ruggles (1996) analyzed TANF/SNAP eligibility and participation. They find that SNAP participation rates between 54 and 66 percent of those eligible. These rates are similar to those reported by Ross (1988). Blank and Ruggles also calculate TANF participation rates between 62 and 70 percent, which is “similar to prior research” (Blank and Ruggles 1996, 65). Leading up to the welfare reform of 1996, several studies considered the effect of local area unemployment on TANF participation. While the unemployment rate was commonly included in earlier analyses, this was typically as a control variable and at an aggregated level (e.g., state unemployment rate; O’Neill, Bassi, and Wolf 1987). (NEED MORE ON THIS) 2.2.2. The Effects of the Welfare Reform Since the enactment of PRWORA, TANF research has focused largely on the effects of welfare reform. TANF participation peaked in 1994 with an average monthly caseload of 5.05 million families. Afterwards, participation nearly halved to an average monthly caseload of 2.26 11 million families in 2000. Given this steep decline in TANF participation, researchers wanted to determine how much of the decline could be attributed to PRWORA. One recent study finds that most of the steep decline in TANF participation was attributed to PRWORA (Snarr 2013). This finding contradicts earlier studies that claim the steep decline in TANF participation was due to the declining unemployment rate (Klerman and Haider 2004) or individual-level characteristics (Teitler, Reichman, and Nepomnyaschy 2007). Ultimately, the decline in TANF caseloads cannot be attributed to the reform alone. (NEED MORE FOR THIS SUBSECTION) What were the expectations of the post-reform world? Were these expectations realized? 2.2.3. TANF, SNAP, and Substance Use The popular opinion leading up to PRWORA was that TANF recipients were drug addicts and abusers (see Califano 1995). Prevalence rates prior to the PRWORA were between 10 percent and 30 percent for TANF recipients (Grant and Dawson 1996; Pollack and Reuter 2006). According to one study, this is greater than that of nonrecipients rate of about 8 percent to 12 percent (Pollack and Reuter 2006). This is misleading, however, because one must be careful to make comparisons between appropriate groups. In this case, we should compare recipients to low-income nonrecipients instead of all nonrecipients. Only a few studies attempt to determine the relationship between substance use and TANF participation. The first study used data from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79, discussed in Section 4) to examine the relationship between illicit substance use and TANF participation (Kaestner 1998). He finds that marijuana use is positively related to future TANF participation. According to his calculations, the effect is modest. He reports that “if marijuana use among welfare participants was reduced to the level of nonparticipants, welfare 12 participation would decline by approximately 5 percent among nonblacks and 3 percent among blacks” (Kaestner 1998, 514). Discuss the following papers here o (Schmidt et al. 2002; Nam 2005; Grant and Dawson 1996; Pollack et al. 2002; Cheng and Lo 2010; Luck, Elifson, and Sterk 2004; Meara and Frank 2006) While some research has focused on substance use only, there is a body of literature that includes substance use as one barrier to employment. This body of literature examines the effect of severe/multiple barriers to employment such as poor physical health, poor education, psychiatric disorders, lack of transportation, language barrier, immigration concerns, domestic violence, and lack of child care (Danziger et al. 2000; Taylor and Barusch 2004; Nam 2005; Meara and Frank 2006; Zabkiewicz and Schmidt 2007). The interest in severe/multiple barriers to employment stems from the drastic decline in TANF caseloads from 1996 through the early 2000s. States were able to move the easily employed off TANF. These studies are motivated by the idea that recipients who remained would likely face these severe/multiple barriers to employment. Unfortunately, these studies fail to identify a causal relationship between substance use and TANF entry/exit. These studies do not consider associations between substance use and SNAP, nor do these studies consider program eligibility as an outcome. 3. Conceptual Framework The program participation life cycle has three parts, each of which are affected by substance use differently. First, a household must be eligible for the program. Second, conditional on being eligible, the household must enter the program (i.e., begin participation). Finally, conditional on participating, the household will either continue participation or exit the program (i.e., end 13 participation). Each of these steps is determined by personal and household characteristics and economic conditions. The second step, program entry, is also determined by application processes. The remainder of this section will discuss each of the parts: program eligibility, program entry, and program exit. 3.1. Eligibility The first part of the program participation life cycle is program eligibility. Program eligibility is determined by the specific program’s rules. According to the PRWORA, TANF eligibility is based on multiple criteria (Public Law 104-193 1996). The family must contain a minor child or a pregnant woman. There is also an income test and an asset test such that both income and assets must be below specified limits. State laws determine these limits. In 2013, the minimum highest monthly income for initial eligibility for a family of three was $269 (Alabama), and the maximum highest monthly income for initial eligibility for a family of three was $1,631 (Alaska). TANF asset limits vary greatly from state-to-state. The minimum asset limit in 2013 is $1,000 (Georgia, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas). There are a few states that have no limit (Alabama, Colorado, Hawaii, Louisiana, Maryland, Ohio, Virginia), but among the states with an asset limit, the maximum asset limit is $10,000 (Delaware, Oregon). In addition to these asset limits, states may exempt vehicles from consideration as assets. These exemptions vary from a portion of one vehicle to all vehicles owned by the household. SNAP eligibility is also determined by income and asset tests. Households must meet both gross and net income tests. The gross monthly income test is 130 percent of the federal poverty line, and the net monthly income test is 100 percent of the federal poverty line. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food and Nutrition Service, “gross income means a household’s total, non excluded income, before any deductions have been made” and, “net income means gross income minus allowable deductions” (“Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program 14 (SNAP) - Eligibility” 2014). All households must meet these tests unless all members are receiving TANF, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), or in some places general assistance (GA). This means that recipients of TANF, SSI, or GA are automatically eligible for SNAP. There are multiple components to the SNAP asset test. For fiscal year 2015, “households may have $2,250 in countable resources, such as a bank account” (“Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) - Eligibility” 2014). States determine how to handle vehicles as an asset. Resources of TANF recipients and SSI recipients are not counted against the asset test. Other resources that do not count against the asset test include a home and lot and most retirement plans. Studies examining determinants of program eligibility typically focus on the effects of regulation. While regulatory factors are important, nonregulatory factors also require research to guide policies and initiatives aimed at helping participants move toward self-sufficiency. Important nonregulatory factors include race, gender, marital status, age, number of children, and human capital. TANF is available to two-, single-, and no-parent families, but the latter two are more likely to pass income and asset tests. Similarly, while TANF is not restricted to men or women only, recipients are typically female. Program eligible women who do not participate are generally older and white, with fewer children and more education (Blank and Ruggles 1996). Substance use has a role in program eligibility through marital status and the number of children. Several studies find a positive relationship between substance use and unprotected sex or out-of-wedlock birth (Yamaguchi and Kandel 1987; Mensch and Kandel 1992; Kaestner 1996; Cooper 2002; Leigh 2002; Kingree and Betz 2003; Brown and Vanable 2007; Scott-Sheldon, Carey, and Carey 2010). Having a child allows the mother to pass one part of the eligibility criteria. Younger women would also likely be income/asset eligible due to correlation between age and income. In this way, substance use is expected to increase eligibility. 15 Substance use is also associated with delayed marriage (Kaestner 1997). Since two-parent families are less likely to pass income/asset tests (i.e., two-parent families have income/assets above the test thresholds), delayed marriage means the mother is more likely to be program eligible longer than mothers who marry sooner. This suggests that substance users are more likely to be program eligible than nonusers. Thus, I expect my empirical analysis to yield a positive relationship between substance use and program eligibility. 3.2. Entry The second part of the program participation life cycle is program entry. This is the moment when, conditional on program eligibility, an individual transitions from eligibility to participation. Like the first step, program entry is determined by personal characteristics, household characteristics, and economic conditions. In addition to these factors, application processes determine program entry. Individuals must complete an application, and have that application accepted, before they become a participant. There are various costs associated with program application. The individual must spend time completing the application. As part of this, the individual must typically travel to a public assistance office. Substance use can affect the application process in two ways. First, substance use impairs cognitive ability (Birnbaum et al. 1980; Steele and Josephs 1990). This would make it difficult for the applicant to complete the application or to provide the correct application information. Second, substance use affects the real application costs because substance use and leisure are likely complements (Kaestner 1994; Alexandre and French 2004; Cook and Peters 2005; West and Parry 2009; French et al. 2011). Thus, women who are substance users would be less likely to be employed and more likely to participate in TANF than women who are nonusers. 16 Another aspect that is unobservable to researchers is the notion of “welfare stigma”, which represents the disutility of program participation (Moffitt 1983). Welfare stigma encompasses several unobservable factors such as the costs of applying and complying with program regulation. Substance use could decrease unobservable welfare stigma. As discussed by Kaestner (1998), young adult substance users “have greater peer than parental influences, are less likely to attend religious services, have greater attitudinal tolerance for deviance, are more likely to participate in illegal activities, and are more likely to have low self-esteem” (see also Kandel 1980; Kandel 1982; Rosenbaum and Kandel 1990). These correlates would likely decrease welfare stigma, thus, increasing the probability of participation. The decision to participate is based on the expected net benefit of participating. If the expected net benefit is positive (negative), then the individual will (not) participate. There are several factors that affect the expected net benefit of participating including the benefit guarantee, the local wage rate, the minimum wage, and future earnings expectations. The benefit guarantee is the amount of assistance awarded. An increase in the benefit guarantee decreases the amount of income required to stay on the same budget constraint. This provides incentive to participate in the program and against working. The local wage rate, the minimum wage, and future earnings expectations have an inverse relationship with program participation. Higher (lower) values for each of these make program participation less (more) appealing and employment more (less) appealing. 3.3. Exit The third part of the program participation life cycle is program exit. This is the moment when, conditional on program participation, an individual transitions from participation to nonparticipation. For this study, exits fall into one of two classifications. An individual can exit while they are still program eligible, or an individual can exit when they become program ineligible. 17 Henceforth, the former will be called “exit-eligible,” and the latter will be called “exit-ineligible.” Program exit is determined by personal characteristics, household characteristics, and economic conditions. Many of the factors contributing to program eligibility also contribute to program exit. Participants must continue to be program eligible to remain participants. Otherwise, program exit is forced. For example, TANF eligibility requires the household to contain a minor child. Program eligibility ceases when these children leave the household. The same is true of income. SNAP and TANF eligibility require income to be below a given threshold. If income increases above this threshold, then program exit would be forced. The application processes affecting program entry also affect program exit because participants are required to reapply for benefits regularly. Income increases can happen different ways. One way is through employment, which increases earned income. Employment is correlated with work experience and the unemployment rate. This means women with more work experience are more likely to become employed. Another way income can increase is through marriage, which increases household income. TANF exits occur earlier for older white women, who are more educated and who have fewer children and more income (Hutchens 1981; Plotnick 1983; Ellwood 1986; O’Neill, Bassi, and Wolf 1987; Blank 1989; Nam 2005; Ribar 2005; Kim 2010). Total time on TANF, the benefit guarantee, urban residence, disability, child health problems, and lack of transportation are negatively associated with exits (Hutchens 1981; Plotnick 1983; Rank 1985; Ellwood 1986; O’Neill, Bassi, and Wolf 1987; Nam 2005; Ribar 2005; Kim 2010). Substance dependence is negatively associated with TANF exits (Schmidt et al. 2002; Nam 2005). These exits are more likely to occur through family-related exits (e.g., loss of child custody) or administrative exits (e.g., sanction or imprisonment). Custody losses would result from child abuse (e.g., the violent drinker) or neglect (e.g., the absent-minded “stoner”). Sanctions occur when the 18 participant fails to comply with requirements. This would include failure to complete paperwork or failure to meet work requirements within the corresponding time limit. Imprisonment could result from drug-related charges that violate the Gramm amendment (i.e., felony drug use, possession, or distribution). 4. Data This dissertation requires individual data on TANF participation, SNAP participation, and substance use collected during the post-reform era. I also require data on state-level policy variables to be used as instruments in my econometric analyses. This section will begin with a general discussion of possible data sources on program participation and substance use. Then I will discuss the policy data sources. 4.1. Program Participation and Substance Use Data Several publicly available datasets are commonly used in the public assistance literature, such as the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY). The Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), administered by the U.S. Census Bureau, consists of a series of nationally representative panels that last about four years each. The SIPP is one of the best sources for program participation data. The purpose of the SIPP is to inform policymakers about the success of government assistance programs and how the U.S. economic well-being changes over time. Unfortunately, the SIPP contains no information on substance use. Thus, the SIPP is not a suitable data source for this dissertation. Like the SIPP, the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) contains information on program participation. The PSID is a survey administered by the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan. From 1968 until 1997, the PSID was an annual survey and became biennial 19 thereafter. The PSID consists of a nationally representative sample and their descendants. The PSID is commonly used to investigate labor market outcomes and poverty. Unlike the SIPP, the PSID contains some information about substance use. Unfortunately, the PSID only contains one year of information about substance use. This is insufficient for this dissertation. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) is an annual, national survey sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services and collected by RTI International. The NSDUH is an excellent source of substance use information, providing data on tobacco use, alcohol use, illicit drug use and mental health in the U.S. The NSDUH has insufficient information about program participation. There is information on the number of months of “welfare receipt” and information on if the household received food stamps. Another problem with the NSDUH is that the survey is cross sectional. This is problematic because we only observe individuals for one year. This is inappropriate for this dissertation. There are several National Longitudinal Surveys, three of which continue today. The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79) is an annual survey of men and women that began in 1979. The NLSY79 Children and Young Adults (NLSY79C), which began in 1986, is a biennial survey of the biological children of women in the NLSY79. The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97) is an annual survey of men and women that began in 1997. Each of these included longitudinal data on program participation and substance use, but they are not all appropriate for this dissertation. The NLSY79 (and NLSY79C?) contain inconsistent information on substance use, and most of their data are from before the TANF era. The NLSY97, however, collects substance use information every year, and the data are from the TANF era. For these reasons, the NLSY97 are appropriate for this dissertation. The NLSY97 is an annual survey consisting of individuals born between January 1, 1980, and December 31, 1984. At the time of the first interview, respondents were aged 12 to 18. The 20 initial survey consists of 8,984 individuals, of which 51 percent are male and 51.9 percent are nonblack/non-Hispanic. The NLSY97 contains two subsamples. The first is a cross-sectional sample designed to be representative of people living in the US during 1997 and born between 1980 and 1984. The second is a supplemental sample designed to oversample Hispanic or Latino and black people living in the US during 1997 and born between 1980 and 1984. My data are limited to years where public assistance questions are asked (1997 through 2009). Table 1 contains information on changes in the sample size resulting from various sample restrictions. First, I restrict my sample to female respondents because the majority of TANF recipients are female. Dropping male respondents decreases the sample by 4,599 persons and 57,005 person-years (51.2 percent). Next, I drop all observations prior to respondents’ 18 th birthday to avoid time when the respondents are child-only cases. There is no change in person observations, but 12,453 person-years are lost (10.7 percent relative to the original sample). Finally, I drop noninterview observations, reducing the sample by 6,516 person years (5.6 percent relative to the original sample). The analysis sample consists of 4,385 person observations and 38,036 person-years. Table 1 – Sample Restrictions % D Person-Years Sample Size D Person- - PersonYears 116,792 Years - … relative to previous row - … relative to the original sample - 4,385 -4,599 57,005 -59,787 51.1910% 51.1910% Drop observations prior to 18th birthday 4,385 -0 44,421 -12,584 22.0753% 10.7747% Drop non-interview observations 4,385 -0 37,905 -6,516 14.6687% 5.5791% Drop respondents who ever miss an interview 4,385 -0 28,045 -9,860 26.0124% 8.4424% Restriction None (Original Sample) Persons 8,984 D Persons Drop male respondents 21 4.2. State-level Policy Data In addition to the individual-level data in the NLSY97, this dissertation will require state- level policy data. These policy data will include information on state-level alcohol policies, marijuana policies, alcohol and marijuana prices, and alcohol taxes. These data will be used to address concerns about endogeneity. The Alcohol Policy Information System (APIS) will be my source for information on alcohol taxes and prices. The APIS is a database containing information on both State and Federal alcohol-related policy. The APIS covers the following: alcohol beverage control; taxation and pricing; transportation, crime, and public safety; health care services and financing; and alcohol and pregnancy. Marijuana prices o www.priceofweed.com o www.hightimes.com/tag/thmq Marijuana decriminalization laws Unemployment rate (BLS – www.bls.gov/lau/data.htm) Maximum benefit award (Welfare rules database) Benefit reduction rate (Welfare rules database) Other State-specific TANF/SNAP policies 5. Estimation Strategy 6. Conclusion References Alexandre, Pierre Kebreau, and Michael T. French. 2004. “Further Evidence on the Labor Market Effects of Addiction: Chronic Drug Use and Employment in Metropolitan Miami.” Contemporary Economic Policy 22 (3): 382–93. doi:10.1111/%28ISSN%291465-7287. Bane, Mary Jo, and David T. Ellwood. 1983. “The Dynamics of Dependence: The Routes to SelfSufficiency.” Cambridge: Urban Systems Research and Engineering. 22 Birnbaum, Isabel M., Joellen T. Hartley, Marcia K. Johnson, and Thomas H. Taylor. 1980. “Alcohol and Elaborative Schemas for Sentences.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory 6 (3): 293–300. Blank, Rebecca M. 1989. “Analyzing the Length of Welfare Spells.” Journal of Public Economics 39 (3): 245–73. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(89)90029-7. Blank, Rebecca M., and Patricia Ruggles. 1996. “When Do Women Use Aid to Families with Dependent Children and Food Stamps? The Dynamics of Eligibility Versus Participation.” The Journal of Human Resources 31 (1): 57. doi:10.2307/146043. Brown, Jennifer L., and Peter A. Vanable. 2007. “Alcohol Use, Partner Type, and Risky Sexual Behavior among College Students: Findings from an Event-Level Study.” Addictive Behaviors 32 (12): 2940–52. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.011. Califano, Joseph. 1995. “It’s Drugs, Stupid.” New York Times Magazine, January 29. Cheng, Tyrone C., and Celia C. Lo. 2010. “Heavy Alcohol Use, Alcohol and Drug Screening and Their Relationship to Mothers’ Welfare Participation: A Temporal-Ordered Causal Analysis.” Journal of Social Policy 39 (04): 543–59. doi:10.1017/S004727941000022X. Coe, Richard D. 1983. “Nonparticipation in Welfare Programs by Eligible Households: The Case of the Food Stamp Program.” Journal of Economic Issues 17 (4): 1035–56. doi:http://mesharpe.metapress.com/openurl.asp?genre=journal&issn=0021-3624. Coll, Blanche. 1995. Safety Net: Welfare and Social Security, 1929-1979. 1St Edition edition. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press. Cook, Philip J., and Bethany Peters. 2005. “The Myth of the Drinker’s Bonus.” Working Paper 11902. National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w11902. Cooper, M. Lynne. 2002. “Alcohol Use and Risky Sexual Behavior among College Students and Youth: Evaluating the Evidence.” Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, no. 14: 101. Danziger, Sandra, Mary Corcoran, Sheldon Danziger, Colleen Heflin, Ariel Kalil, Judith Levine, Daniel Rosen, Kristin S. Seefeldt, Kristine Siefert, and Richard M. Tolman. 2000. “Barriers to the Employment of Welfare Recipients.” In Prosperity for All?: The Economic Boom and African Americans, edited by Robert Cherry and William M. Rodgers III. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. “Drug Testing for Welfare Recipients and Public Assistance.” 2014. National Conference of State Legislatures. December 29. http://www.ncsl.org/research/human-services/drug-testing-andpublic-assistance.aspx. Ellwood, David T. 1986. “Targeting ‘Would-Be’ Long-Term Recipients of AFDC.” Cambridge: Harvard University, Mathematica Policy Research. French, Michael T., Johanna Catherine Maclean, Jody L. Sindelar, and Hai Fang. 2011. “The Morning after: Alcohol Misuse and Employment Problems.” Applied Economics 43 (21): 2705–20. doi:10.1080/00036840903357421. Gordon, L., and F. Batlan. 2011. “Aid To Dependent Children: The Legal History.” Social Welfare History Project. http://www.socialwelfarehistory.com/programs/aid-to-dependent-childrenthe-legal-history/. Grant, Bridget F., and Deborah A. Dawson. 1996. “Alcohol and Drug Use, Abuse, and Dependence among Welfare Recipients.” American Journal of Public Health 86 (10): 1450–54. Grogger, Jeffrey, and Lynn A. Karoly. 2005. Welfare Reform : Effects of a Decade of Change. Cambridge, Mass: RAND Corporation. Hutchens, Robert M. 1981. “Entry and Exit Transitions in a Government Transfer Program: The Case of Aid to Families with Dependent Children.” Journal of Human Resources 16 (2): 217–37. doi:http://jhr.uwpress.org/content/by/year. 23 Kaestner, Robert. 1994. “The Effect of Illicit Drug Use on the Labor Supply of Young Adults.” Journal of Human Resources 29 (1): 126–55. ———. 1996. “Drug Use, Culture, and Welfare Incentives: Correlates of Family Structure and outof-Wedlock Birth.” Baruch College. ———. 1997. “The Effects of Cocaine and Marijuana Use on Marriage and Marital Stability.” Journal of Family Issues 18 (2): 145–73. doi:10.1177/019251397018002003. ———. 1998. “Drug Use and AFDC Participation: Is There a Connection?” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 17 (3): 495–520. Kandel, Denise B. 1980. “Drug and Drinking Behavior Among Youth.” Annual Review of Sociology 6 (January): 235–85. ———. 1982. “Epidemiological and Psychosocial Perspectives on Adolescent Drug Use.” Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry 21 (4): 328–47. doi:10.1016/S0002-7138(09)60936-5. Katz, Michael B. 1996. In the Shadow Of the Poorhouse: A Social History Of Welfare In America, Tenth Anniversary Edition. Second Edition edition. New York: Basic Books. ———. 2013. The Undeserving Poor: America’s Enduring Confrontation with Poverty: Fully Updated and Revised. 2 edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Kim, Jeounghee. 2010. “Welfare-to-Work Programs and the Dynamics of TANF Use.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 31 (2): 198–211. doi:10.1007/s10834-010-9180-9. Kingree, J.B, and Heidi Betz. 2003. “Risky Sexual Behavior in Relation to Marijuana and Alcohol Use among African–American, Male Adolescent Detainees and Their Female Partners.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 72 (2): 197–203. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(03)00196-0. Klerman, Jacob Alex, and Steven J. Haider. 2004. “A Stock-Flow Analysis of the Welfare Caseload.” The Journal of Human Resources 39 (4): 865. doi:10.2307/3559030. Leigh, Barbara C. 2002. “Alcohol and Condom Use: A Meta-Analysis of Event-Level Studies.” Sexually Transmitted Diseases 29 (8): 476–82. Luck, Philip A., Kirk W. Elifson, and Claire E. Sterk. 2004. “Female Drug Users and the Welfare System: A Qualitative Exploration.” Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy 11 (2): 113–28. doi:10.1080/0968763031000152504. Meara, Ellen, and Richard Frank. 2006. “Welfare Reform, Work Requirements, and Employment Barriers.” National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w12480. Mensch, Barbara, and Denise B. Kandel. 1992. “Drug Use as a Risk Factor for Premarital Teen Pregnancy and Abortion in a National Sample of Young White Women.” Demography 29 (3): 409–29. doi:10.2307/2061826. Moffitt, Robert. 1983. “An Economic Model of Welfare Stigma.” American Economic Review 73 (5): 1023–35. Nam, Yunju. 2005. “The Roles of Employment Barriers in Welfare Exits and Reentries after Welfare Reform: Event History Analyses.” Social Service Review 79 (2): 268–93. doi:10.1086/428956. O’Neill, June A., Laurie J. Bassi, and Douglas A. Wolf. 1987. “The Duration of Welfare Spells.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 69 (2): 241–48. doi:10.2307/1927231. Plotnick, Robert. 1983. “Turnover in the AFDC Population: An Event History Analysis.” Journal of Human Resources 18 (1): 65–81. doi:http://jhr.uwpress.org/content/by/year. Pollack, Harold A., Sheldon Danziger, Rukmalie Jayakody, and Kristin S. Seefeldt. 2002. “Drug Testing Welfare Recipients—false Positives, False Negatives, Unanticipated Opportunities.” Women’s Health Issues 12 (1): 23–31. Pollack, Harold A., and Peter Reuter. 2006. “Welfare Receipt and Substance-Abuse Treatment among Low-Income Mothers: The Impact of Welfare Reform.” American Journal of Public Health 96 (11): 2024–31. Public Law 73-10. 1933. Agricultural Adjustment Act. 24 Public Law 74-271. 1935. Social Security Act. Public Law 88-525. 1964. The Food Stamp Act of 1964. Public Law 97-35. 1981. Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act. Public Law 100-435. 1988. Hunger Prevention Act. Public Law 100-485. 1988. Family Support Act. Public Law 104-193. 1996. Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1966. Public Law 111-5. 2009. American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. Rank, Mark R. 1985. “Exiting from Welfare: A Life-Table Analysis.” Social Service Review 59 (3): 358– 76. Ribar, David C. 2005. “Transitions from Welfare and the Employment Prospects of Low-Skill Workers.” Southern Economic Journal, 514–33. Rosenbaum, Emily, and Denise B. Kandel. 1990. “Early Onset of Adolescent Sexual Behavior and Drug Involvement.” Journal of Marriage and Family 52 (3): 783–98. doi:10.2307/352942. Ross, Christine. 1988. “The Food Stamp Program: Eligibility and Participation.” U.S. Congress: Congressional Budget Office. Schmidt, Laura, Daniel Dohan, James Wiley, and Denise Zabkiewicz. 2002. “Addiction and Welfare Dependency: Interpreting the Connection.” Social Problems 49 (2): 221–41. doi:10.1525/sp.2002.49.2.221. Scott-Sheldon, Lori A. J., Michael P. Carey, and Kate B. Carey. 2010. “Alcohol and Risky Sexual Behavior Among Heavy Drinking College Students.” AIDS and Behavior 14 (4): 845–53. doi:10.1007/s10461-008-9426-9. Snarr, Hal W. 2013. “Was It the Economy or Reform That Precipitated the Steep Decline in the US Welfare Caseload?” Applied Economics 45 (4): 525–40. doi:10.1080/00036846.2011.607135. Steele, Claude M., and Robert A. Josephs. 1990. “Alcohol Myopia: Its Prized and Dangerous Effects.” American Psychologist 45 (8): 921–33. Stern, Mark J., and June J. Axinn. 2011. Social Welfare: A History of the American Response to Need, 8th Edition. 8th edition. Pearson. “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) - Eligibility.” 2014. Eligibility | Food and Nutrition Service. October 3. http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/eligibility. Taylor, Mary Jane, and Amanda Smith Barusch. 2004. “Personal, Family, and Multiple Barriers of Long-Term Welfare Recipients.” Social Work 49 (2): 175–83. Teitler, Julien O., Nancy E. Reichman, and Lenna Nepomnyaschy. 2007. “Determinants of TANF Participation: A Multilevel Analysis.” Social Service Review 81 (4): 633–56. doi:10.1086/522770. “The History of SNAP | Snap To Health.” 2015. Accessed February 27. http://www.snaptohealth.org/snap/the-history-of-snap/. Trattner, Walter I. 1998. From Poor Law to Welfare State, 6th Edition: A History of Social Welfare in America. 6 Sub edition. New York: Free Press. West, Sarah E., and Ian W. H. Parry. 2009. “Alcohol/Leisure Complementarity: Empirical Estimates and Implications for Tax Policy.” doi:http://www.rff.org/documents/RFF-DP-09-09.pdf. Wiseman, Michael. 1977. “Change and Turnover in a Welfare Population.” University of California, Berkeley: Institute of Business and Economic Research. Yamaguchi, Kazuo, and Denise Kandel. 1987. “Drug Use and Other Determinants of Premarital Pregnancy and Its Outcome: A Dynamic Analysis of Competing Life Events.” Journal of Marriage and Family 49 (2): 257–70. doi:10.2307/352298. Zabkiewicz, Denise, and Laura A. Schmidt. 2007. “Behavioral Health Problems as Barriers to Work: Results from a 6-Year Panel Study of Welfare Recipients.” Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 34 (2): 168–85. 25