Appendix B4: Recommendations for Distance Education at UWSP Date: August 23, 2013 To:

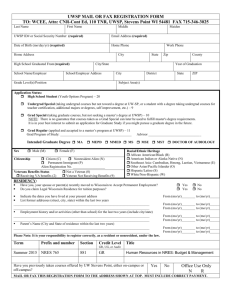

advertisement