ARTICLE 29 DATA PROTECTION WORKING PARTY 01248/07/EN

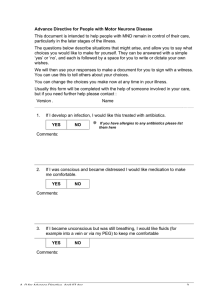

advertisement