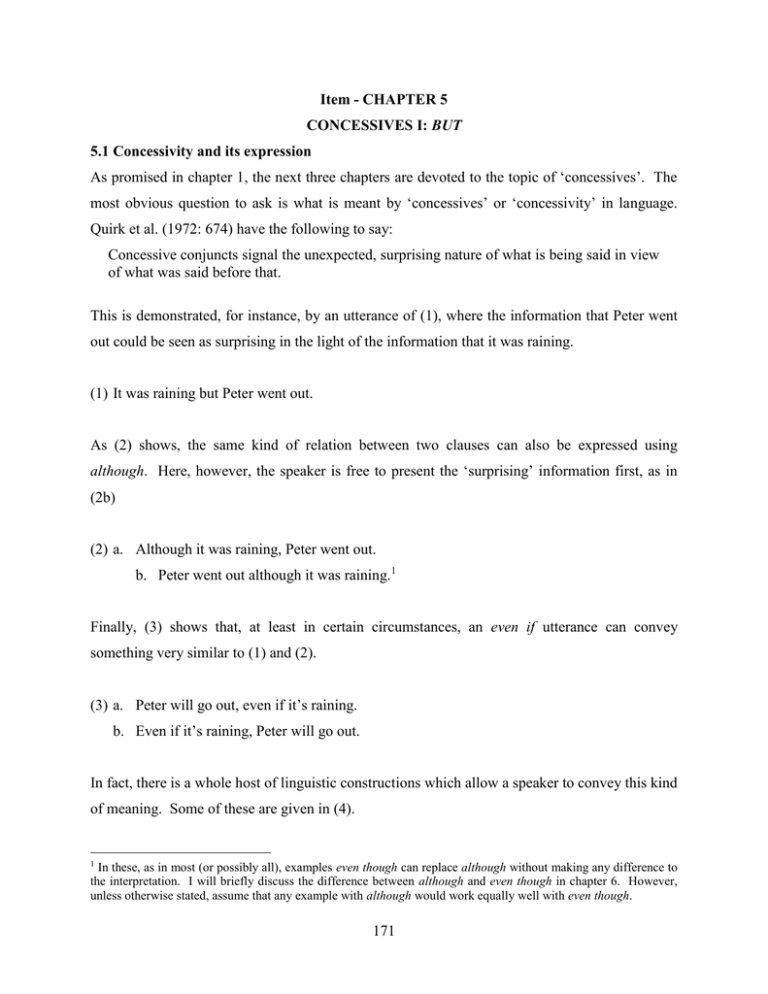

As promised in chapter 1, the next three chapters are... most obvious question to ask ... Item - CHAPTER 5 BUT

advertisement