Macon Telegraph, GA 11-20-07

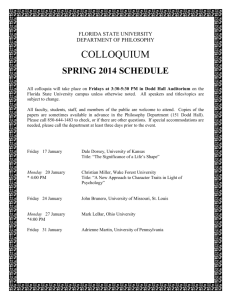

advertisement

Macon Telegraph, GA 11-20-07 Dodd's spent lifetime in politics, thinks he's due to step up By DAVID LIGHTMAN - McClatchy Newspapers WASHINGTON Christopher Dodd, then a rookie U.S. senator, eagerly opposed Dr. C. Everett Koop's nomination to be surgeon general in 1981, arguing that "his personal beliefs would keep him from impartial judgments." Koop, whom the news media described as "a noted anti-abortionist" at the time, won confirmation easily and turned out to be a popular, articulate health-care spokesman. A few months later, a chastened Dodd sent him a note, apologizing. "I voted against him, and I regret it," Dodd would say, "because he turned out to be one fine surgeon general." The story is vintage Dodd. "He sees the big picture, and he works on a very human scale," said Rep. Rosa DeLauro, D-Conn., a longtime friend and confidante. But the Koop story also illustrates what skeptics say is Dodd's biggest weakness: He's too much a creature of Washington. "All he has is Washington experience, and that's an enormous burden," said Steffan Schmidt, a professor of political science at Iowa State University. "His image outside Washington is that he's a tax-and-spend liberal." Dodd counters that that's too simplistic, but Washington unquestionably has shaped him. Dodd's political roots stretch back to his father, Sen. Thomas J. Dodd of Connecticut, who served from 1959 to 1971. His career was broken in 1967, when the Senate censured him for using campaign money for personal purposes. Tom Dodd never recovered: He lost his 1970 re-election bid badly and died at age 64, five months after he left office. His son made it his mission to restore honor to his father and their name. "Sometimes, I think almost everything Chris Dodd does down here is meant to vindicate his father," said Sen. Daniel Inouye, D-Hawaii, who served with both men. Chris Dodd sits at his father's desk in his Senate office, and an illuminated life-sized portrait of Tom Dodd hangs there. Equally important, though, is how Dodd grew up watching and enjoying the peculiar rhythms of the U.S. Capitol. He loved the action, the process, the people. When he was 30 in 1974, he triumphed in a tough primary and won an eastern Connecticut seat in the House of Representatives. Six years later, when Democratic incumbents were falling as rarely before in the 20th century, Dodd became one of two freshmen Democrats elected to the Senate. He had an innate understanding of the institution. His father's Senate friends counseled him, and the young senator patiently built a reputation and seniority on the Banking, Labor and Foreign Relations committees, hoping someday to emulate mentors such as Tennessee's Jim Sasser and Maryland's Paul Sarbanes, who quietly crafted sweeping consensus legislation. From them, Dodd learned patience and the value of collegiality. He'd come to the Senate at a highly polarized time, when conservatives were newly ascendant and Republicans had won control for the first time in 26 years. Dodd made alliances with Republican colleagues who were hardly political soul mates: Pennsylvania's Arlen Specter on children's issues, Texas' Phil Gramm on securities law, Utah's Orrin Hatch on family legislation, Nebraska's Chuck Hagel on infrastructure overhaul. Dodd became a highly popular insider, so much so that when Sasser, in line to be the next Democratic Senate leader, was upset in his 1994 re-election bid, veteran senators urged Dodd to jump into the race. He wound up losing his lastminute effort to Tom Daschle by one vote, but President Clinton noticed. Clinton offered him the general chairmanship of the Democratic Party; a shocking choice, since Dodd had never been active in party affairs and was viewed outside Washington as the kind of Northeastern liberal who'd just led the party to electoral ruin. Dodd took the job and toured the country, charming skeptics, finding common ground in state after state. But his new job came at a price. He was the chairman in 1995 and 1996, a time when Clinton was letting big donors sleep in the Lincoln bedroom or have coffee with White House big shots. A Senate committee investigated. While it found that Dodd had done nothing wrong, the controversy kept him from seeking the vice presidential nomination in 2000 when Al Gore's representatives asked whether he wanted to be considered. Instead, the nod went to Connecticut's junior senator, Joseph Lieberman. That blocked Dodd from the White House not only in 2000 but also in 2004, when Lieberman sought the office and Dodd deferred to his more prominent homestate colleague. Dodd thought his time had finally come this year, but his Democratic rivals contest his natural constituencies. Hillary Clinton is the darling of Wall Street and the Northeastern liberal crowd. Illinois Sen. Barack Obama and Clinton are the favorites of the black community, whom Dodd has championed throughout his career. Dodd speaks fluent Spanish and served in the Peace Corps in the Dominican Republic, but Latino voters may be drawn more to New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson, who's Hispanic. Even in foreign relations expertise, Dodd, number two on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, is vying with the panel's chairman, Delaware Sen. Joseph Biden. Ironically, Dodd, who stresses his experience, still has to overcome his resume. "All people know of Dodd is that he's from the U.S. Senate," said Dennis Goldford, a professor of politics at Drake University in Des Moines. Typically, Dodd betrays no disappointment, no frustration at such talk. Sit with him on a long bus ride through Iowa, talk to him on the streets of New Hampshire, and he betrays no anger or irritation. After all, this is a man for whom things usually have worked out. He spent many years mired in the Senate minority, but now he's the chairman of the Banking Committee. He's seen his father's reputation restored: Today there's a research center at the University of Connecticut and a minor-league ballpark in Norwich named for Tom Dodd. He himself just finished writing a book about the senior Dodd's experiences as a prosecutor in the Nuremberg war-crimes trials after World War II. Patience and perseverance, Dodd is convinced, will pay off.