Sleep Deprivation Chapter 4 4001. CHALLENGES OF SLEEP DEPRIVATION

advertisement

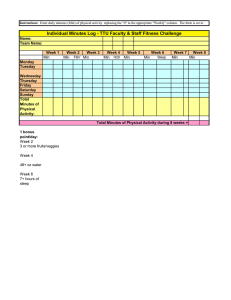

Chapter 4 Sleep Deprivation 4001. CHALLENGES OF SLEEP DEPRIVATION People accumulate a “sleep debt” (cumulative loss of sleep over time) when they perform under limited sleep conditions. The only corrective measure for satisfying this sleep debt is sleep itself. Military operations, by their demanding nature, create situations where obtaining needed sleep will be difficult or impossible for more than short periods. Continuous operations are military operations with many pulses of action every day and night, continuing for several days to weeks, which require careful planning and resource allocation to give everyone a minimum of 4 hours sleep in 24. (FM 22-51) Sustained operations are continuous operations or combat with opportunity for less than 4 hours sleep per 24 hours for significant personnel, which may be brief or fragmented. (FM 22-51) Accordingly, service members may have opportunities for only limited or fragmented sleep over an extended period. As a result of these periods of sleep loss, several combat tasks are likely to show decreased performance. These tasks include the following: l Orientation with friendly and enemy forces (knowledge of the squad’s location and maintaining camouflage, cover, and concealment). 58 _______________________________________________ l Coordination and information processing (coordinating firing with other vehicles and dismounted elements, reporting vehicle readiness, and communicating with the headquarters). l Combat activity (firing from bounding vehicle, checking the condition of weapons, observing the terrain for enemy presence). l Force preservation and regrouping (covering disengaging squads, marking the routes between locations, and conducting reconnaissance). l Command and control activity (directing location repositioning, directing mounted defense, assigning fire zones and targets). MCRP 6-11C Continuous operations will potentially be more commonplace on the battlefield. In offensive operations, darkness is the time to retain or gain the initiative; while in defensive operations, obstacles can be employed with greater security during darkness. Forces can disengage undetected and threats to close air support lessen. The physical environment changes at night. As the air cools below ground temperature, inversions reduce visibility and hamper radar and radio signals. Conditions are optimal for using chemical weapons. Visual changes also occur. Without the aid of white light, there is no color perception. There is also a decrease in visual clarity, field of view, and depth perception. Targets take longer to engage. Preparation time increases two-fold to six-fold. Simple actions, such as the departure and return of patrols, become more complex and dangerous. Nighttime planning and coordination require greater attention. Navigation, adjusting fire, and munitions and/or target matching are more difficult. Precision is essential, but accuracy has a price. Service members tend to maintain accuracy at the sacrifice of speed. The adverse conditions associated with or generated by continuous ground combat at night will degrade the fighting performance of Service members, teams, and units. The almost complete mechanization of Combat Stress _____________________________________________ 59 land combat forces and technological advances that permit effective movement at night, during poor weather conditions, and under conditions of limited visibility have largely overcome the reasons for “traditional” pauses in battle, such as darkness, resupply, and regrouping. New technologies have significantly increased the range, reduced the time, and changed the conditions over which battles are fought. For example, day/night-capable vehicles can operate for extended periods without re-supply, but they are limited by a crew’s need to sleep. A Service member is not a machine and is, therefore, the weak link in the chain. The equipment can operate longer than the Service member who operates it, as the Service member must have sleep. Commanders and leaders must ensure that all Service members obtain enough rest to counteract the effects of rapidly shifting from daytime to nighttime duty hours, or to extended work schedules. Implementing countermeasures that are designed to help Service members adapt to continuous operations conditions can satisfy this requirement. Neither leaders nor their subordinates can perform without rest or sleep. The Service member, the unit, and the leader are all affected by continuous operations. Generally at night, the cognitive and physiological resources of Service members are not at their peak, especially after a rapid shift from daytime to nighttime duty hours. Fatigue, fear, feelings of isolation, and loss of confidence may increase. Non-stop, unrelieved combat operations (sustained operations) with little or no sleep degrade performance and erode mental abilities more rapidly than physical strength and endurance. Information gained from the Army Unit Resiliency Analysis Model shows that even healthy young Service members who eat and drink properly experience a 25 percent loss in mental performance for each successive 24-hour period without sleep. The mental parameters include decisionmaking, reasoning, memory 60 _______________________________________________ MCRP 6-11C tasks, and computational tasks. The loss may be greater for Service members who are older, less physically fit, or who do not eat and drink properly. The effects of sustained operations are sometimes hidden and difficult to detect. Units are obviously impaired when Service members are killed or wounded in action or become noncombatant losses. They are further impaired when their troops are too tired to perform their tasks. Unlike individual performance, unit performance does not deteriorate gradually. Units fail catastrophically, with little warning. A priority for fighting units is to assure that commanders and leaders are rested and able to think clearly. While this is obvious, it is a most difficult lesson for leaders to learn. During combat, commanders must focus on the human factor. They must assess and strengthen their units as they plan and fight battles. They must accurately decipher which units must lead, which must be replaced, where the effort must be reinforced, and where tenacity or audacity and subsequent success can be exploited. When leaders begin to fail, control and direction become ineffective, and the organization disintegrates. No fighting unit can endure when its primary objectives are no longer coordinated. Leaders must also prepare and precondition Service members to survive. It is particularly important that leaders conscientiously plan and implement effective sleep plans, because activities that are most dependent on reasoning, thinking, problem solving, and decision-making are those that suffer most when sleep and rest are neglected. Some leaders wrongly believe that their round-the-clock presence during an operation is mandatory; they are unwilling to recognize that they, too, are subject to the effects of sleep deprivation. If the unit has been regularly trained according to the mission command philosophy, two benefits accrue. Not only will a leader be confident that in his absence his subordinates will adhere to his intent, Combat Stress _____________________________________________ 61 but the trust he shows in his subordinates will continue to maintain unit morale and help ease some of the stress of the situation. In future operations, the battlefield will become increasingly lethal. The threat of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons will maximize confusion, uncertainty, and stress, which adversely impact our ability to move, shoot, communicate, and sustain. Sleep loss in this type of environment increases an already stressful situation. 4002. EFFECTS OF SUSTAINED OPERATIONS ON PERFORMANCE A basic rule for continuous operations is planning ahead to avoid sustained operations, and provide members 5 to 6 hours sleep in 24. However, missions or enemy actions sometimes require exceptional exertion for several days with only unpredictable, fragmented sleep—as required in sustained operations. Sustained combat leads to exhaustion and reduction in effective task performance. Even during the first night of combat, normal sleeping habits and routines are abnormal. The Service member feels the effects of fatigue and the pressure of stress from noise, disrupted sleep time, and threat to life. While essential for endurance, sheer determination cannot offset the mounting effects of adverse conditions. Cognitive degradation involving poor decisionmaking begins during and after the first 24 hours of sleep deprivation. Individual and unit military effectiveness is dependent upon initiative, motivation, physical strength, endurance, and the ability to think clearly, accurately, and quickly. The longer a Service member goes without sleep, the more his thinking slows and becomes confused. Lapses in attention occur, and speed is sacrificed to maintain accuracy. Continuous work declines more rapidly than intermittent work. 62 _______________________________________________ MCRP 6-11C Tasks such as requesting fire, integrating range cards, establishing positions, and coordinating squad tactics become more difficult than well-practiced, routine physical tasks, such as loading magazines and marching. Without sleep, Service members can perform the simpler and/or clearer tasks—lifting, digging, and marching—longer than the more complicated or ambiguous tasks such as a fine hand-eye coordination sequence; i.e., tracking a target through a scope. Sleep loss affects memory, reasoning, mental assessments, decision-making, problem-solving, subsequent actions, and overall effectiveness. While comprehension is accurate, reading speed slows and recall fails. For example, Service members may understand orders when reading them in documents, yet they are forgotten later when required. Individuals will forget or omit assigned tasks more often than they will make errors in carrying them out. Leaders can expect declining moods, motivation, initiative, planning ability, and preventive maintenance. High motivation will only increase risk, due to impaired performance. Leaders must recognize erratic or unreliable task performance in subordinates, as well as in themselves. Alertness and performance decline gradually with partial sleep deprivation; that is, when sleep is limited to 4 to 5 hours per night. After 5 to 7 days of partial sleep deprivation, alertness and performance decline to the same low levels as those following 2 days of total sleep deprivation. After 48 to 72 hours without sleep, personnel become militarily ineffective. Adverse Conditions Continuous combat forces Service members to perform under adverse conditions that cause degradation in performance. Examples of adverse conditions follow. Combat Stress _____________________________________________ 63 Low Light Level The amount of light available for seeing landmarks, targets, and maps is greatly reduced at twilight and night. Limited Visibility Smoke, fog, rain, snow, ice, and glare degrade a Service member’s ability to see his environment and objects within it, as opposed to situations free of such conditions. Disrupted Sleep Routines People are accustomed to being awake or asleep during certain hours of the day or night. Disruption of the normal sleeping schedule causes degraded performance. Physical Fatigue Working the muscles faster than they can be supplied with oxygen and fuel rapidly creates “oxygen debt,” eventually making these muscles unable to function until the deficits are made up during brief rests. Sleep Loss The muscles can continue to function adequately without sleep, but the brain cannot. Increasing sleep debt leads to subtle, but potentially critical, performance failures. Sleep Loss Indicators Indications of degraded performance symptoms become more prevalent as sleep debt accumulates. Performance is affected by the hours of wakefulness, tolerance to sleep loss, and the types of mental or physical work. Both mental and physical changes occur, with symptoms varying among individuals. Leaders must observe Service members for the following indications of sleep loss and degraded performance: 64 _______________________________________________ l Physical changes in appearance, including vacant stares, bloodshot eyes, pale skin, and poor personal hygiene. Other physical signs of sleep loss include the body swaying when standing, sudden dropping of the chin when sitting, occasional loss of hand-grip strength, walking into obstacles or ditches, low body temperature, slowed heart rate, and slurred speech. l Mood changes, decreased willingness to work, and diminished performance go hand-in-hand. Service members may experience decreasing levels of energy, alertness, interest in their surroundings, and cheerfulness with a concurrent increase in irritability, negativity, and sleepiness. Some become depressed and apathetic. Others, for a time, can become energized by sleep loss, talk more, and may be more assertive without necessarily maintaining good judgment. Sleepiness and mood changes are not signs of weakness. After long periods of sleep loss, Service members go from being irritable and negative to dull and weary. l Service members may feel more effort is needed to perform a physical task in the morning than in the afternoon. Exaggerated feelings of physical exertion may lead to work stoppage, especially between 0400 and 0700. During that time, the tendency to fall asleep is considerably more noticeable than other times. l Both bickering and irritability increase with sleep loss. When Service members argue, it shows that they are still talking to each other and exchanging orders and messages. When arguments cease, especially after a period of increased bickering, Service members may be in a state of mental exhaustion. l Comprehension and perception slow considerably. Individuals require extended time to understand oral, written or coded information; to find a location on a map and/or chart coordinates; to interpret changes in enemy fire patterns; and to make sense of things seen or heard, especially patterns. They may MCRP 6-11C Combat Stress _____________________________________________ 65 have difficulty with spot status or damage reports, and may be unable to assess simple tactical situations. Loss of Concentration Sleep deprivation causes the attention span to shorten. There is a loss of concentration on the job as dream-like thoughts cause lapses in attention. Leaders should watch for the following: l Decreased vigilance. Personnel are less alert and fail to detect the appearance of targets, especially in monotonous environments. They may doze off at the wheel of moving vehicles. l Distorted attention. Service members may imagine seeing things that are not there, e.g., “moving” bushes when in reality there is no such movement. The sleep-deprived brain can also misperceive bushes, rocks, people, vehicles or anything else and see them as something different, in very precise detail. Often the tired brain “sees” what it wishes were there (food, a bed); at other times, these illusions may be animals or other more bizarre things. But when the mind is alert for an enemy, the brain may generate a very convincing, detailed image of the enemy. Sometimes, but not usually, sounds or other sensations may accompany these illusions. They usually last only seconds, but can persist for minutes if not challenged, and rarely have even been “seen” by equally sleep-deprived comrades when told of them. It is essential for sleep-deprived unit members to check out any questionable things they see with their comrades, and to faithfully follow reporting and challenge procedures. l Inability to concentrate; easily confused. Service members cannot keep their minds on what they are doing. They cannot follow multiple directions nor perform numerical calculations. 66 _______________________________________________ l Failure to complete routine tasks. Sleep loss interferes with completing routine individual tasks, such as drying the feet, changing socks or filling canteens when water is available. Tasks such as performing weapons checks may be skipped. MCRP 6-11C When a Service member cannot recall what he just saw, read, heard or was told by another individual, he is exhibiting a common sign of sleep loss. His memory loss is limited to recent events. For example, a sleep-deprived Service member may forget recent target data elements or recall them incorrectly and have difficulty learning new information. 4003. ACHIEVING SLEEP IN COMBAT Sleep deprivation produces stress and, therefore, sleep management is important. Sleep management is a combat multiplier. Planned sleep routines are important for keeping the unit, the individual Service members, and the leader himself functioning as required while reducing sleepiness during continuous combat. Since leaders are responsible for planning sleep routines, they need a basic understanding of the physiological and behavioral aspects of sleep and their impact on performance. The following paragraphs provide this information. Rhythmic Variations There are rhythmic variations in individual performance based on a predictable physiological and behavioral cycle that comprises about 24 hours. The 24-hour, day-night/work-rest cycle is called the circadian rhythm. Because traveling across a half-dozen time zones disrupts the usual relationship in the day-night/work-rest cycle, for a few days Service members are not sleepiest at their usual sleep period of 2400 to 0600, new-locale time. Allowing Combat Stress _____________________________________________ 67 sleep about 1200 to 1800, new-locale time, will only delay their adaptation to their new locale. Leaders must instruct troops to go to bed between 2400 and 0600 new-local time to establish a new circadian rhythm. Another example of circadian rhythm is body temperature. Although one’s “normal” temperature is 98.6 degrees, this is really an average or midpoint of a daily swing from 96.8 to 100.8 degrees. For someone accustomed to working days and sleeping nights, body temperature would fluctuate approximately as indicated. There is a well-established link between body temperature and sleepiness and/or performance slumps. Performance parallels body temperature. The higher the body temperature, the better the performance. As body temperature decreases, mood and motivation decline with a concurrent increase in sleepiness and fatigue. Impact upon performance is most pronounced during the circadian lull, which is roughly 0200 to 0600 hours. During this time, performance declines about 10 to 15 percent. In sleep-deprived Service members, this decline may reach 35 to 40 percent. If the day-night/work-rest cycle is disrupted, performance suffers because the Service member is sleepy during the new work period and awake during the new sleep period. The body needs several days to adjust to the new schedule. Critical hours for sleep are between 0200 and 0600 when anchor sleep (the most beneficial sleep) is taken. The body is at its lowest temperature during this period. This is the best time for sleeping, but not for napping. To prevent sleep inertia, naps should always be taken at times other than the lowest point in body temperature. Leaders need to calculate the difference in time zones and make the necessary schedule changes. Leaders will need day-and nightfighting teams. Members acclimated to working days and sleeping nights should be scheduled to work nights and sleep days. 68 _______________________________________________ MCRP 6-11C Their performance slump/optimal time to sleep would be 2400 to 0600, new-locale time. Deployment, pre-combat, and combat are not usual circumstances. If certain Service members must have an offset circadian timing from the rest of the unit, a special effort must be made to establish their sleeping time. Obviously, troops must sleep whenever possible. If a planned sleep schedule cannot be followed, however, performance is enhanced if sleep coincides with the low point in body temperature. Adjusting to new circadian rhythms is a slow process, taking 3 to 6 days to come “in phase” with a new schedule. Leaders should devise a sleep schedule that provides for sleep at the same time of day or night every 24 hours. Sleep schedules that provide for sleep at different times of day or night are less valuable and are detrimental to quality sleep and optimal performance. Sleep Shifts Staggered work schedules can be set up for two shifts working 4 hours on/4 hours off, 6 hours on/6 hours off, and 12 hours on/12 hours off. See Table 4-1. Each shift follows the same schedule daily. It is better to maintain regular shift schedules than schedules that continually change. Sleep/Rest Guidelines Leaders should use the following sleep and/or rest guidelines in this section to enhance individual and the unit performance in continuous operations. l Know personal tolerance for sleep loss and those under your command; major individual differences are not easily changed. Individuals who are unable to sleep during predeployment and deployment stages should be encouraged to practice relaxation exercises (see paragraph 2005). Combat Stress _____________________________________________ 69 Table 4-1. Sleep Shifts. 4 HOURS ON/4 HOURS OFF Shift 24000400 04000800 08001200 12001600 16002000 20002400 1 SLEEP DUTY SLEEP DUTY SLEEP DUTY 2 DUTY SLEEP DUTY SLEEP DUTY SLEEP 6 HOURS ON/6 HOURS OFF Shift 24000600 06001200 12001800 18002400 1 SLEEP DUTY SLEEP DUTY 2 DUTY SLEEP DUTY SLEEP 12 HOURS ON/ 12 HOURS OFF Shift 24001200 12002400 1 SLEEP DUTY 2 DUTY SLEEP l Ensure that Service members fully use their breaks and other opportunities for rest. Encourage them to waste no time in getting to sleep. Undisturbed, prolonged sleep is the most desirable use of rest opportunities. When there has been sleep loss but little physical exertion (e.g., manning communications, operating a radio), mild physical exercise such as walking around when conditions permit, can help maintain alertness. l Encourage Service members to sleep, not just rest, by creating the most conducive environment possible for sleep: quiet, without interruptions (or earplugs); dimness or darkness (or with eye cover); not overly warm or cold. 70 _______________________________________________ l Do not allow personnel to sleep in unsafe conditions. Enforce strict rules designating sleep areas and requiring perimeter guards. Require day and night guides for all vehicles to prevent Service members from being accidentally run over. l Ensure that Service members follow sleep schedules or routines. The field commander who does not enforce a sleep schedule or routine leads his troops into an environment that increases the opportunity for hazardous conditions to be encountered while in continuous combat. Taking naps is not a sign of low fighting spirit or weakness; it is a sign of foresight. MCRP 6-11C Measuring Sleep Loss Sleep loss can be measured by: l Keeping a sleep and/or activity log. From pre-deployment to post-deployment, log sleep and nap periods. Service members need 4 to 5 hours per 24-hour period; 6 or 7 hours is optimum. If they receive less, the first chance for a long rest period must be used for sleep. l Observing performance and asking questions. Look for the indications of sleep loss—such as increase in error occurrence, irritability, difficulty understanding information, and attention lapses—with concurrent decreases in initiative, short-term memory, and attention to personal hygiene. Confirm sleep loss by asking the obvious question: “When did you sleep last and how long did you sleep?” Sleep Loss Alternatives Ways to overcome performance degradation include: l Upon signs of diminished performance, find time for members to nap, change routines or rotate jobs (if cross-trained). Combat Stress _____________________________________________ 71 l Have the Service members most affected by sleep loss execute a self-paced task. l Have Service members execute a task as a team, using the buddy system. l Do not allow Service members to be awakened for meals while in flight to a new location, especially if the time zone of the destination is several hours different than that of point of departure. l Insist that Service members empty their bladder before going to bed. Awakening to urinate interrupts sleep, and getting in and out of bed may disturb others and interrupt their sleep. l Allocate sleep by priority. Leaders, on whose decisions mission success and unit survival depend, must get the highest priority and largest allocation of sleep. Second priority is given to Service members that have guard duty and to those whose jobs require them to perform calculations, make judgments, sustain attention, evaluate information, and perform tasks that require a degree of precision and alertness. 4004. SLEEP/REST PLANNING Sleep/rest planning applies to the pre-deployment, deployment, pre-combat, combat, and post-combat stages of battle. Pre-Deployment Stage Using mission-scenario operation guidelines, determine periods available for sleep and the total number of sleep hours possible. Because continuous operations requirements may change, alternate sleep routines should be planned. Become familiar with the area where the combat unit will sleep; For example, some may 72 _______________________________________________ MCRP 6-11C have to sleep in mission-oriented protective posture (MOPP) IV. If sleeping in MOPP IV is anticipated in combat, practice it during the pre-deployment stage. Prior experience reduces stress, so practice anticipated sleep routines before continuous operations. Deployment Stage Since sleep will be reduced during deployment, follow preplanned sleep routines. The prudent commander will choose a 4hour on/4-hour off, 6-hour on/6-hour off, or 12-hour on/12-hour off shifts from the start. Take into account that Service members on night duty will need to sleep during the daytime. Provide night-shift personnel with separate sleeping quarters to avoid disruption of their sleep period. Pre-Combat Stage In general, people are most effective during the afternoon and are least effective just before dawn. Without prior adjustment to the new time zone, which naturally occurs in 3 to 5 days, leaders can expect degraded daytime performance. The reason is that 0200 to 0600 hours home-base time is the low point in performance efficiency and should be considered when planning workloads. Combat Stage Every effort should be made to avoid situations where all personnel are physically and mentally exhausted simultaneously. Make the most of any lull during the combat phase by sleeping briefly. Complete recovery from sleep loss may not be possible during intense combat, but limited sleep is helpful. Uninterrupted short sleeps of 15 minutes or longer are beneficial to partially recovering alertness. Sleep during the combat stage may be risky, how- Combat Stress _____________________________________________ 73 ever, because a Service member may wake up feeling groggy, confused, sluggish, and uncoordinated. It may take his brain from several seconds to 15 minutes to “warm up.” Individuals differ in how quickly they take to wake up, but it tends to be worse when the body expected to go into deep sleep, and to get worse with increasing sleep loss. Activities that increase circulation of warm blood to the brain, like moderate exercise or drinking a hot beverage, may shorten the start-up time. Post-Combat Stage It is important to make up sleep debt, but experts disagree about the amount of recovery time needed. Some say the hours of sleep needed for recovery after sleep deprivation are less than the amount lost. It is well known and documented that lost sleep is not made up hour-for-hour. Most experts agree that immediately following continuous combat, Service members should be allowed to sleep up to 10 hours. Longer sleep periods are not desirable because they cause “sleep drunkenness” and delay in getting back to a normal schedule. After the first sleep period of up to 10 hours, Service members should return to the regular sleep routine. Sleep inertia lasting longer than 5 to 15 minutes and increased sleepiness may occur for as long as a week following sustained combat. Some experts recommend that 4 of the first 8 hours of recovery sleep should be at the 0200 to 0600 sleep time, and they suggest the following guidelines for complete recovery from the effects of sleep loss: l 12 hours for sleep and rest after 36 to 48 hours of complete sleep loss with light to moderate work load (fatigue may linger for 3 days). l 24 hours for sleep and rest after 36 to 48 hours of sleep loss with high workload (12 to 16 hours per day). 74 _______________________________________________ l 2 to 3 days time off after 72 hours or more of acute sleep loss. l As much as 5 days for sleep and rest following 96 hours or more of complete sleep loss. MCRP 6-11C Most experts agree that 10 hours of sleep is the maximum needed, with the additional 2 hours used for rest. It is doubtful that a Service member could continue past 72 hours of wakefulness. Should this occur, a couple of nights with 10 hours of sleep are more beneficial than an excess of 10 hours during one sleep period. If Service members have not slept for 36 to 48 hours or more, they should avoid sleep of less than 2 hours, especially between 0400 and 0600. A too-short sleep period at the wrong time may cause a long period of sleep inertia. After 96 hours of total wakefulness, 4 hours of sleep may provide substantial recovery for the simpler, less-vulnerable tasks. Recovery continues with additional days of 4 hours of sleep per 24 hours. Complex leadership tasks may require longer recovery sleep, but sleep until fully satisfied is not necessary. Sleep loss alone does not cause permanent health problems, nor does it cause mentally healthy people to become mentally ill. Reduced sleep (from 8 to 4 hours) does not cause physical harm. Hallucinations may occur, but they disappear after recovery sleep. Clinical laboratory tests show that total sleep loss of over a week does not pose serious health problems. It is doubtful that Service members could stay awake for such an extended period, and it is not suggested that Service members try to endure long periods without rest. However, the effects of sleep loss, such as inattentiveness and poor judgment, may be harmful (such as falling asleep at the wheel of a vehicle). Sleep cannot be stored in our bodies for emergency use. Sleep of more than 7 to 8 hours before deployment does not “store up” Combat Stress _____________________________________________ 75 excess sleep, but sleep taken immediately before a deployment can prolong activity. Therefore, it is important to begin continuous operations in a rested state. During daytime or early morning naps, many Service members experience vivid dreams as they fall asleep and often wake up frightened. Leaders should inform their troops that this occurrence is both common and normal during daytime sleep. If a single, unbroken period of 4 to 5 hours is not available for sleep, “power naps” of 15 to 30 minutes, although less recuperative, can be taken. Leaders must capitalize on every opportunity for a “power nap.” Merely resting by stretching out does not take the place of sleep. Only sleep can satisfy the need for sleep.