Document 11701333

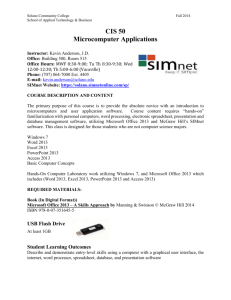

advertisement