Design Zone Professional Development Summative Report

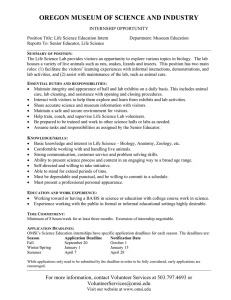

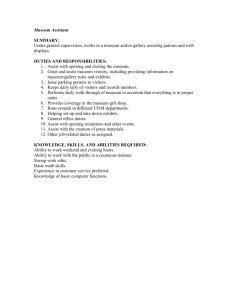

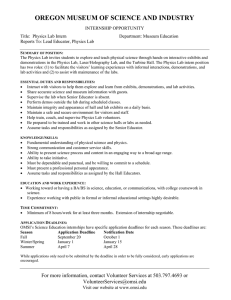

advertisement