Nuclear Weapons Research in Sweden Research SKI Report 02:18

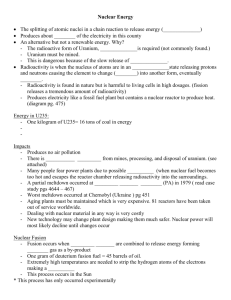

advertisement