Visit our website for other free publication downloads

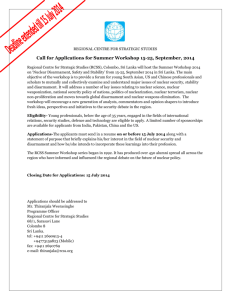

advertisement