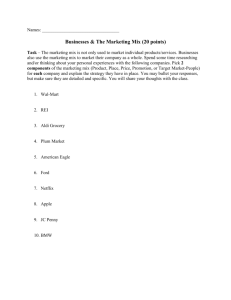

Streaming is the New Black: A Consumer-based Examination of Netflix... Original Programming and Streaming Strategy

advertisement